In the 1970s, the Universities Computer Centre was home to the country’s first computer and an elite group of students who were among the lucky few to study overseas under the Ne Win regime.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

IN THE hours after U Htin Kyaw was nominated as the NLD’s leading candidate for the presidency on March 10, journalists around the world scrambled to uncover his life story. Only after he’d been described widely as Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s driver, incorrectly said to have studied economics at Oxford, and even been confused with another U Htin Kyaw, a political activist, did the party decide to post a biography to Facebook.

It focused primarily on his long academic and civil service career. One particular phase stood out as unusual: From 1971 to 1975 he studied computer science, including at the now-defunct University of London Institute of Computer Science, before joining the Ministry of Industry.

A common reaction: Computer science? In Myanmar? In the 1970s?

Myanmar’s new president was among the first students to join the Universities Computer Centre, which was set up under a United Nations Development Programme-funded project implemented by UNESCO.

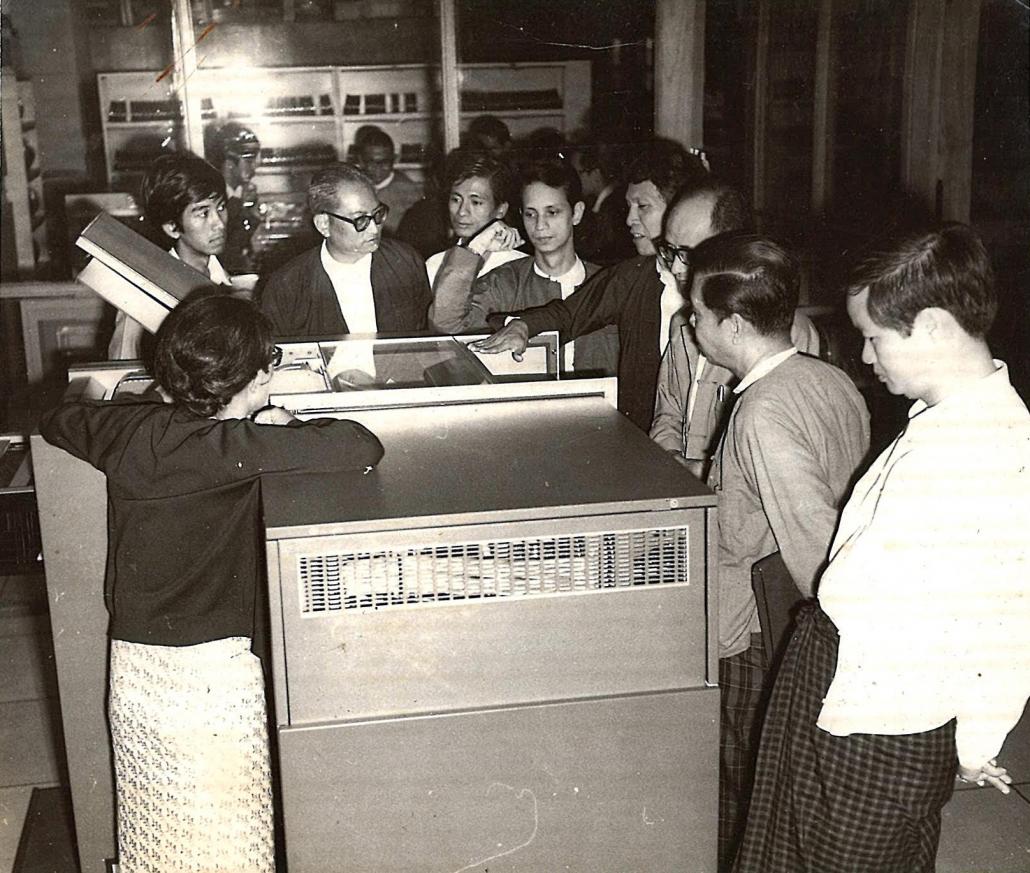

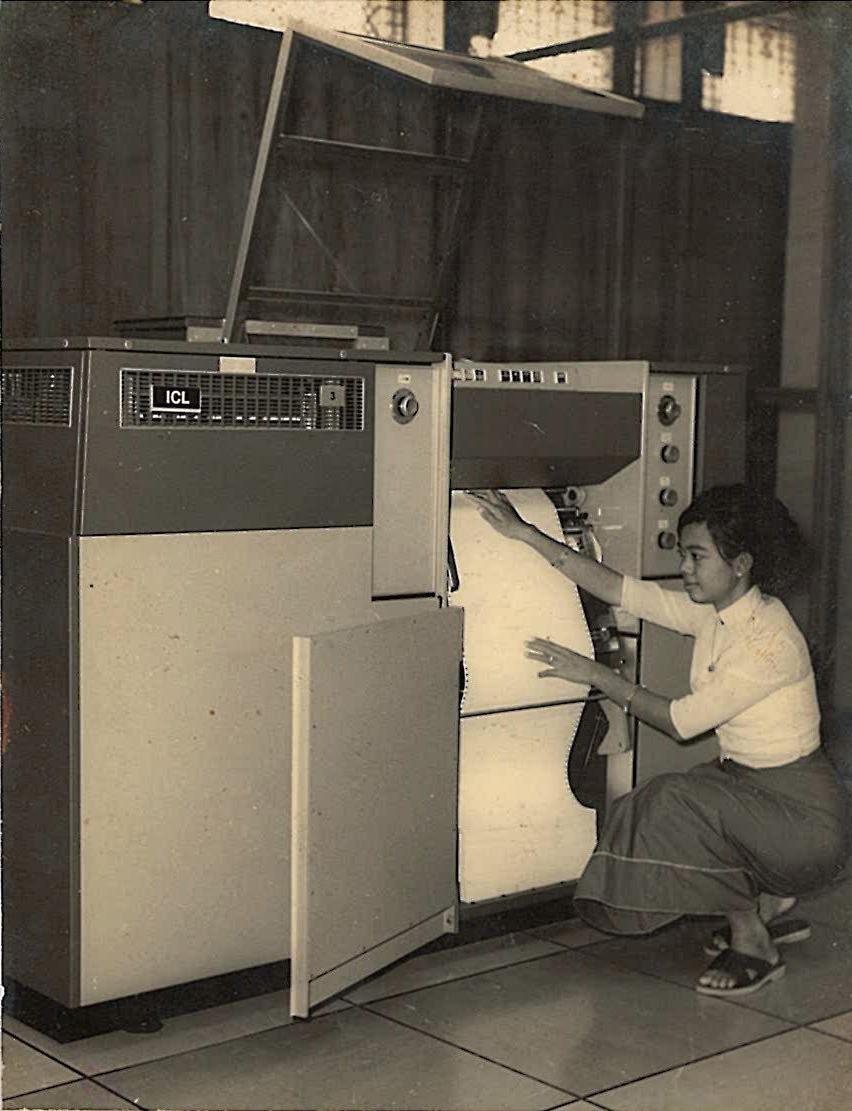

A computer operator uses the ICL 1902S as a visiting United Nations official watches on. (Supplied)

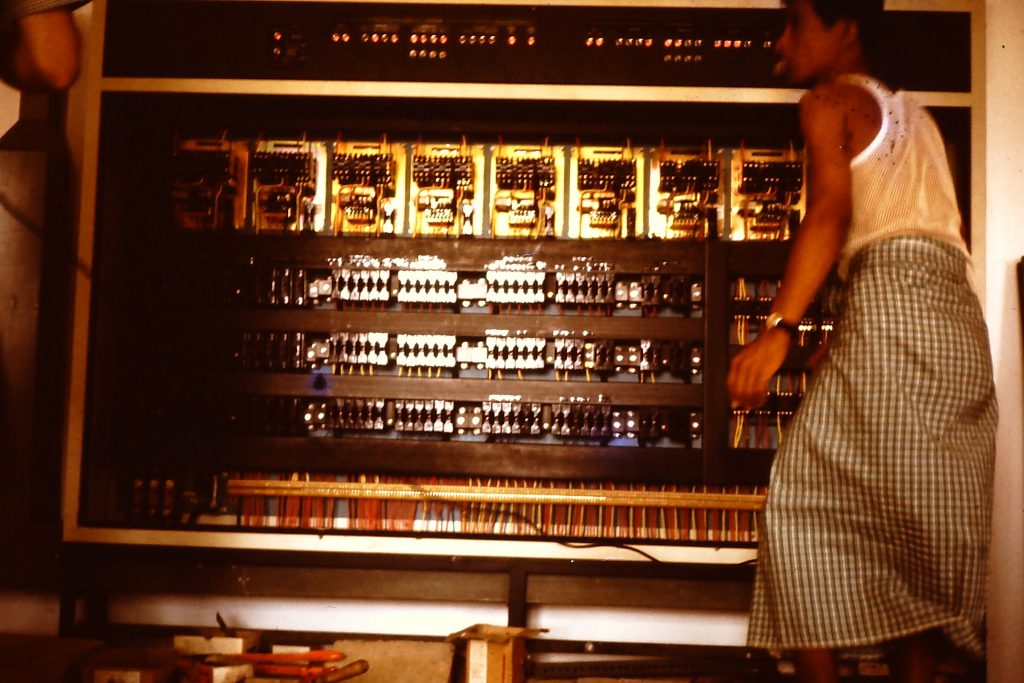

The project resulted in the delivery of Myanmar’s first computer – a mainframe known as the ICL 1902S, produced by International Computers Limited – and brought a host of global computer experts to Myanmar on short and long-term visits.

At a time when microprocessors and personal computers were still just a dream, the UCC and the ICL 1902S laid the foundations for the development of Myanmar’s ICT sector, which began to take off after the fall of the socialist regime in 1988.

Given its significance, though, the story of Myanmar’s first computer – including those who made it possible, and those like Htin Kyaw who were trained to program it – has received surprisingly little attention, with few, if any, accounts published in English.

A decade-long dream

The campaign for a computer required patience and persistence: The early advocates, nearly all of whom had been exposed to computers while studying overseas, would have to wait nearly 10 years before the ICL 1902S was installed in Yangon.

The push for a computer began at the Institute of Economics in the 1960s. The project captured the optimism of the early Ne Win era, drawing together many of the most talented faculty members from across Yangon’s universities.

At the time, data processing was being conducted with punched cards and unit recording machines, the predecessor of the computer. Only a few government departments had access to these, including Burma Railways, the Central Economics and Statistics Department, and the Tatmadaw’s Records Office.

class=

The project leader was Dr Chit Swe. The head of the economics institute’s mathematics department, he had returned to Myanmar in 1964 after obtaining a PhD in mathematics from the University of Liverpool.

While abroad, he’d seen how computers could assist with academic research and believed that Myanmar needed to join the IT revolution or risk being left behind. His campaign gained Ministry of Education support, and he began the lengthy process of applying for assistance from the United Nations.

Another key figure was U Soe Paing. He fell into computers; he was selected for a government scholarship, and ended up at Stanford University because he thought the East Coast and Midwest would be too cold, and a friend who also received a scholarship had an uncle in the Bay Area.

While completing a bachelor’s and then master’s degrees in electrical engineering, Soe Paing saw friends with printouts from the university’s computers.

Curious, he took some courses in programming and data processing, and volunteered as an operator in the university’s computer centre, where he transferred punched cards onto magnetic tape storage.

“We didn’t know Stanford was [a leader in computer] – we only realised when we went there and came back,” he said during a recent interview with Frontier in his Mayangone Township home.

U Soe Paing speaks to Frontier at his Yangon home. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

When Soe Paing returned in October 1963, he found his new employer, Rangoon Institute of Technology, still closed following the student-led protests the previous year.

“While the institute was closed, those who had been abroad were supposed to give lectures to our colleagues so I talked about computers and programming, and one of the instructors reported what I did to Dr Chit Swe,” he said.

A few weeks later, Chit Swe reached out to Soe Paing and asked whether he would join the project team. “I readily said yes. From that time onward I joined the project to put the first computer in Burma,” Soe Paing said.

Soe Paing continued to work at Rangoon Institute of Technology, and from 1966 began recruiting bright students for the computer project. However, the computer project took longer than expected to get off the ground, and many of the students took up jobs elsewhere, he recalled.

The delays were due to “administrative formalities”, he said, including UN bureaucracy. “Everybody was committed to making it happen.”

Mr Sheldon Bachus, a foreign expert who spent one year on the project in 1973-74, said bureaucracy within both the UN and the Burmese government conspired to slow progress.

There was also competition between the various academic institutions – particularly the Institute of Technology and the Institute of Economics – for the new computer to be housed within their individual departments, he said.

“It is a credit to everybody involved that these issues were negotiated and resolved,” he said, “even if it took nearly 10 years to do so!”

Falling into place

By the late 1960s, negotiations with the UN had begun to move forward. In 1970, a grant contract was signed and the Universities’ Computer Centre Project was established the following year.

Set up under the Department of Higher Education, the UCC was designed to not only house the computer and related equipment, but also develop a pool of well-trained programmers and operators. The project was also expected to train government staff and conduct pilot projects across a range of fields.

In 1970, Chit Swe had travelled to Paris with UNESCO to select the computer model. The field had been narrowed to IBM and ICL, and the latter offered Myanmar a better deal: it agreed to upgrade its 1902A model to include a scientific option (denoted by the “S” after “1902”) that featured a floating-point processor, which gave it improved performance when conducting calculations.

Discussions also began with architects from Public Works Corporation Design Group about constructing the new UCC building. A three-storey structure on the university’s Hlaing campus was envisaged, with the computer on the first floor, offices on the second and a library and lecture hall on the top.

The ICL 1902S is unloaded at the UCC in December 1972. (Supplied)

U Ko Ko Lay, a structural engineer who would also be integral to the success of the project, travelled to Stanford to gain further advice on the building design; he had previously worked as part-time computer operator with Soe Paing at the Stanford Computation Center.

Recruitment and training began in earnest. From 1970 the civil servants picked to lead the project were sent overseas, to the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, Japan and elsewhere, to gain experience.

The first batch of staff, including Htin Kyaw, were recruited the following year. While Htin Kyaw was at the Institute of Computer Science in London, Soe Paing and another faculty member, U Aung Zaw, were sent to Southampton University.

The University of California at Santa Cruz, which had been awarded a contract to provide support on the project, began sending experts to Yangon.

The foreign expert co-leading the project was Mr Harry Huskey, a professor who led the Department of Computer Science at UCSC. He was an internationally renowned pioneer in computers, having helped to develop the first electronic computer, ENIAC, while at the University of Pennsylvania.

Finally, it arrived: The ICL 1902S was delivered in December 1972 and moved into the computer room, with its air conditioning and cutting-edge power supply, to start the installation process.

Acceptance trials for the ICL 1902S and the environmental equipment started on February 25, 1973, and were formally completed on March 8, 1973.

Nearly four years after the United States first put a man on the moon, Myanmar had its first operational computer.

UCC: The best and brightest

U Thein Oo was a young accounting graduate when he got a call in 1971 asking if he would like to join the University Computer Centre.

The director of the new centre, Chit Swe, was friends with Dr Khin Maung Kyi, who was a research professor at the Institute of Economics in Yangon, where Thein Oo was working. They had apparently been discussing which faculty members would be good candidates for computer training.

At the time Thein Oo knew little about computers or the UCC, but he jumped at the opportunity.

“Honestly, they told me that they would send me abroad, that they would send me to England to study IT. I want to go and study in England so I said okay,” he told Frontier in his office in MICT Park.

Initially he found it tough. The UCC building was not yet complete, so a temporary office was set up in Mandalay Hall on the Yangon Arts and Sciences University campus.

There, students in this new field learned programming through lectures from foreign and local experts. But Thein Oo said that soon after beginning his studies, he began to see the possibilities.

After leaving the civil service in the late 1980s, Thein Oo would eventually set up his own ICT business, Ace Data Systems, and develop the first accounting software specifically for the Myanmar market, in 1992.

Today he is also chairman of Myanmar ICT Development Corporation Limited, which developed MICT Park in the early 2000s. “I realised that IT could be used in my profession as well. At that time I was also interested in accounting, so I can see that IT could be used in accounting quite well,” he said.

The UCC occupied a special position in Myanmar’s tertiary education system. It took in the best students from other universities and other disciplines and equipped them with computer-related skills.

Its students and faculty worked closely together with foreign experts, and had access to overseas study, at a time when Myanmar was mostly shut off from the outside world. “When people asked, ‘Where are you from?’ we could say, ‘I’m from UCC’. We were very proud of that,” recalled Thein Oo.

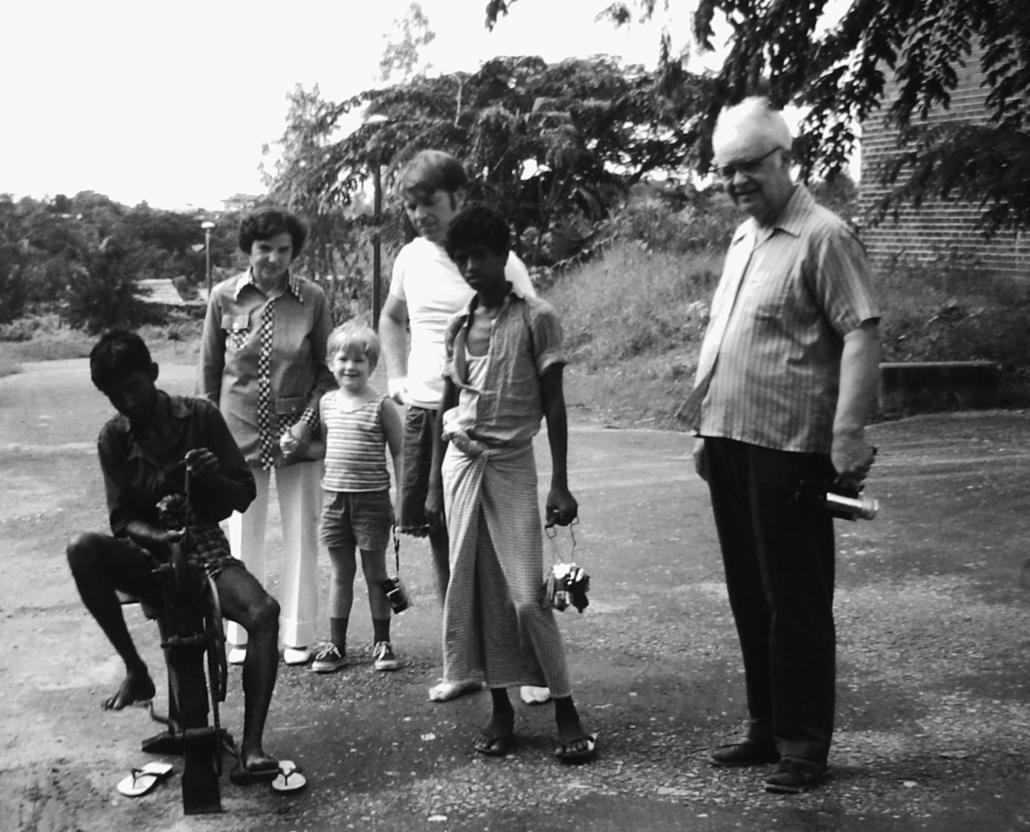

In August 1973, Bachus arrived from Santa Cruz to take up a one-year posting in Burma. At the time, he was the only American expatriate in the country outside the US embassy.

Harry Huskey, right, and Sheldon Bachus, rear, watch on as a man sharpens a knife outside their residence in Yangon. Both Huskey and Bachus worked at University of California at Santa Cruz and were sent to Burma under the UCC project. (Supplied)

Prior to his arrival, Bachus had been serving as acting director of Santa Cruz’s computer centre while Huskey was managing the installation of computer systems around the world under UNESCO contracts – not only in Burma, but also India and Nigeria. When Huskey returned to California, he asked Bachus if he was interested in going to Burma to train government staff in using computer technology.

“My answer was of course yes,” Bachus told Frontier in an email.

He said he believed that the computer project came about because the UN had launched a global program to encourage census taking. Burma had not had a census since 1941, and much of the data from that count had been lost in World War II.

“Using a carrot rather than stick, the UN would promise funding for computers if individual countries would participate in the census-taking program,” he said. Soe Paing recalled events differently, however: He said that UNESCO had never wanted to use the computer for the census, but the government had insisted.

Crunching the numbers

The 1973 census, conducted in April, was the first major practical application for the ICL 1902S. There were two major tasks – data entry and validation, and tabulation – and it would take two years to complete.

Preparations began in 1973, with programmers trained, software designed, and additional memory, disk drives and a card reader acquired.

Data entry began in May 1974 at the Census Department headquarters, in the old Rowe & Co building on Mahabandoola Street, using more than 100 keypunches rented from IBM. At the UCC, computer access time was split up into three shifts, with the evening and night shifts, from 4pm to 8am, reserved for census processing.

Given the long gap between censuses, Soe Paing said it was difficult to estimate how much time and manpower the ICL 1902S saved. “However, we could do more checks on the validity and consistency of the data. The tabulation was definitely faster and more elaborate,” he said. “Another advantage was more tables could be produced or more analysis done from the stored data.”

Given the long gap between censuses, Soe Paing said it was difficult to estimate how much time and manpower the ICL 1902S saved. “However, we could do more checks on the validity and consistency of the data. The tabulation was definitely faster and more elaborate,” he said. “Another advantage was more tables could be produced or more analysis done from the stored data.”

A Universities Computer Centre staff member loads paper into the printer of the ICL 1902S. (Supplied)

But the census was one of many tasks for which the computer was used. While initially the program was envisaged as a training device to introduce computer technology – the UCC introduced postgraduate diploma and masters programs in 1973 – increasingly the government and those at UCC began to see the practical possibilities.

Soe Paing said many government departments started to use the ICL 1902S for data processing, including Burma Railways, the Central Statistical Organization – even the Burma Socialist Programme Party.

On a typical day, Bachus spent the mornings developing computer applications to support government activities, including budgeting, scheduling industrial processes, agricultural resource management, and geological exploration.

“Using these applications as case study material, in the afternoons I would teach post-graduate classes in computer technology, systems analysis, and programming at the Rangoon Institute of Economics. My students would become involved in each application as it was operationally deployed over the one-year course of the project,” he said.

These projects and applications for the ICL 1902S brought the young staff into contact with some of the most senior figures in the government.

“It was exhilarating. We managers were running the show in our early 30s – our assistants were even younger – while experiencing the new technology with complete support from the UN, university administration and the government,” said Soe Paing. “We also got to interact with visiting world-renowned computer scientists … This atmosphere attracted younger talent.”

Thein Oo recalled working on a range of government projects, including malaria and maternal morbidity surveys, and developing auditing systems and factory management plans.

Asked which of the projects he worked on were the most exciting, Thein Oo responded: “All projects were exciting at the time! We were introducing IT to Myanmar.

“We had a chance to work on the national-level projects, even though we were still very young, barely 20. We had to work with high-level organisations like the Central Bank … As young professionals we have very good chance to meet high-level people and work with them.

“I think they were happy as well. ICT was new for everybody. They also want to know what could be achieved with it.”

The UCC legacy

In a paper presented at an International Federation of Automatic Control symposium in Italy in 1979, Bachus wrote that he believed the main problem with the UCC program had been its success: students were complaining that they had trouble getting access, because it was in such high demand.

By this point, the ICL 1902S had been used to develop systems for tidal prediction, petroleum reservoir and pipeline analysis, electrical load flow and network analysis, construction and structural analysis, forest resources analysis, and determining crop yields from irrigation dams.

“The current constraints felt by instructional users of the centre’s computer points to the project’s success rather than a failure,” Bachus wrote.

The UCC was considering its next computer acquisition. On the advice of Huskey, who continued to visit the UCC each year, it acquired a minicomputer, the PDP 11/70, produced by Digital Equipment Corporation, with additional funds from UNDP and UNESCO.

According to Soe Paing, around this time the government decided to split the functions of the UCC, with a new National Computer Center to handle the applications of government departments. The government again sought funding from the UN.

This time though a UN delegation, led by Gunnar Bergren, an inter-regional adviser on computers at the UN Statistical Office, rejected its application – a sign of the deterioration of government capacity and functioning during the second half of the socialist era.

“The mission was not happy with the amount of reliable and consistent data available for processing even if a National Computer Center was established,” Soe Paing wrote in an unpublished account of the history of the UCC.

“The mission ended without any agreement on the part of all parties. Mr Bergren made a few more visits but no agreement was reached. After some time the government stopped agreeing to Mr Bergren’s visits.”

The government then decided to proceed alone, albeit with help from Huskey, who continued to visit. The next purchase, decided by Soe Paing, was a Cromenco microcomputer, which had a Z80 microprocessor with 64kb of memory and two double-sided 8-inch floppy diskette drives.

These were later rolled out into various government departments, and were eventually replaced by IBM compatibles. In March 1988, the UCC would be incorporated into the newly established Institute of Computer Science and Technology.

Its legacy, though, continues to be felt today, through alumni like Thein Oo. Aside from running his own successful business, he has also held senior posts in the Myanmar Computer Professionals Association and Myanmar Computer Federation. “ICT started with the UCC,” he said. “The UCC was the starting point. It [provided] the capacity building, that’s what it was set up to do.”

Soe Paing agreed, saying that while the ICL 1902S got people “hooked” on computers, “it was the activities of the UCC that is significant in the development of ICT in the country”. “

“The environment at UCC was very good. It was very dynamic,” he said. “The main thing was we could really motivate these students; they were so motivated that sometimes after they finished they would test everything at night and not go home; they would sleep over.”

U Soe Paing points to U Htin Kyaw, who stands in the back row in a photo of the first UCC class of master’s students. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

For Soe Paing, it was also the start of a lifetime involvement in computers; after leaving Myanmar in 1980, he travelled the world as a UN consultant. “I feel very lucky that I was in a position to do this project, and I’m still proud of doing this project and creating this computer culture in Burma.

“We have done our part, now I think it’s time to use computers effectively in the government because we have not been able to [until now] … It’s time to use computers in the government for the benefit of the people.”

And where is the computer now? According to Thein Oo and Soe Paing, it remains in a store room at the old UCC building on the Yangon University of Technology campus.

Soe Paing said that given its historical significance, a permanent location should be found. “It should be put on display in the lobby of the main building of the MICT Park.”

A computer, but not as you know it

The ICL 1902S was a far different beast from the computer in your home or office. The 24-bit processor featured the equivalent of about 150kb of memory. The computer together with its accessories took about half of the ground floor of the UCC building. The room had raised flooring, with all the cables stored underneath.

Leaving aside the fact it was much larger and infinitely slower, the biggest difference is in terms of inputting data. Forget about a keyboard or mouse – instead, the ICL used punch cards that were read by a card reader.

Each punch card consisted of 80 columns and 12 rows. The column would be punched to represent a character, meaning that a single card could input up to 80 characters – a single program would require many cards.

To speed up the process, users would write their program or data on coding sheets, and give them to a trained keypuncher. A single error would require both the coding sheet and card to be rewritten. The card reader on the ICL 1902S could read up to 800 cards per minute.

There was a separate computer operator, who could connect to the computer using teletype to select the software, choose the software language and exchange disk drives.

The computer had two very large, portable disk drives (two more were later acquired). “A drive was about the size of a dishwasher,” Soe Paing said. “They seem funny now, because these big disk drives held only 8 megabytes. They were mostly used for temporary storage as well as for the software – most of the data was stored either on cards or on tape.”

Top photo: The central processing unit of the ICL 1902S is installed at the UCC in December 1972. (Supplied)