Eleven Media has long had a reputation for bombastic reporting and aggressive pursuit of its critics. Will it survive the jailing of its outspoken chief executive?

By SEAN GLEESON

DR THAN Htut Aung has been called many things, but coward is not one of them: no one could ever accuse him of backing down from a fight.

As the flamboyant founder and chief executive of the Eleven Media Group, he has built an empire renowned for its bombastic style and crusading attacks on corruption. In the process, it has accumulated a formidable list of enemies. In recent years his publications have been subject to a prodigious number of lawsuits – almost as many as he has filed against his opponents – while last year he was the target of what he says was an assassination attempt.

Despite having made enemies of some of the country’s most powerful people, Eleven has never demurred from its confrontational reporting. Former ministers, business leaders, other journalists and the military alike have all been subjected to barrages of criticism on Eleven’s pages, often in screeds authored by Than Htut Aung himself.

His occasional editorial series, “I Will Tell the Real Truth”, was at times both a measured analysis of Myanmar’s political transition and a staging post for relentless invective directed at the paper’s critics. Through all its public battles, Eleven has assiduously reported on itself, offering a full-throated defence of its conduct while doubling down on its targets.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Yet it is only now, after the installation of Myanmar’s first genuinely civilian government in more than half a century, and international praise at the country’s democratic reforms, that Eleven Media’s future has been imperilled. As Than Htut Aung faces the prospect of a length prison term together with his chief editor, perhaps the real surprise is that the pair were not jailed sooner.

Media behemoth

For a media outlet that has developed a uniquely florid style, perhaps the only thing prosaic about Eleven Media is its name. When its first publication was launched by Than Htut Aung in 2000, it found a quick audience publishing sports news and results from the English Premier League. Its close identification with the sport has led to the casual assumption that the outlet took its name from the number of players on a football side. (The real reason is somewhat more humdrum: Eleven Media Group was simply the 11th organisation to gain a publishing licence from the former military junta.)

What distinguished First Eleven, according to the outlet’s own lore, was the dogged determination of its reporters to watch the matches and hold the presses to provide the most up-to-the-minute results for Myanmar’s football-mad public. The story is indicative of the manner in which the papers editors regard themselves, and their tenacity and their determination to build the country’s most formidable empire.

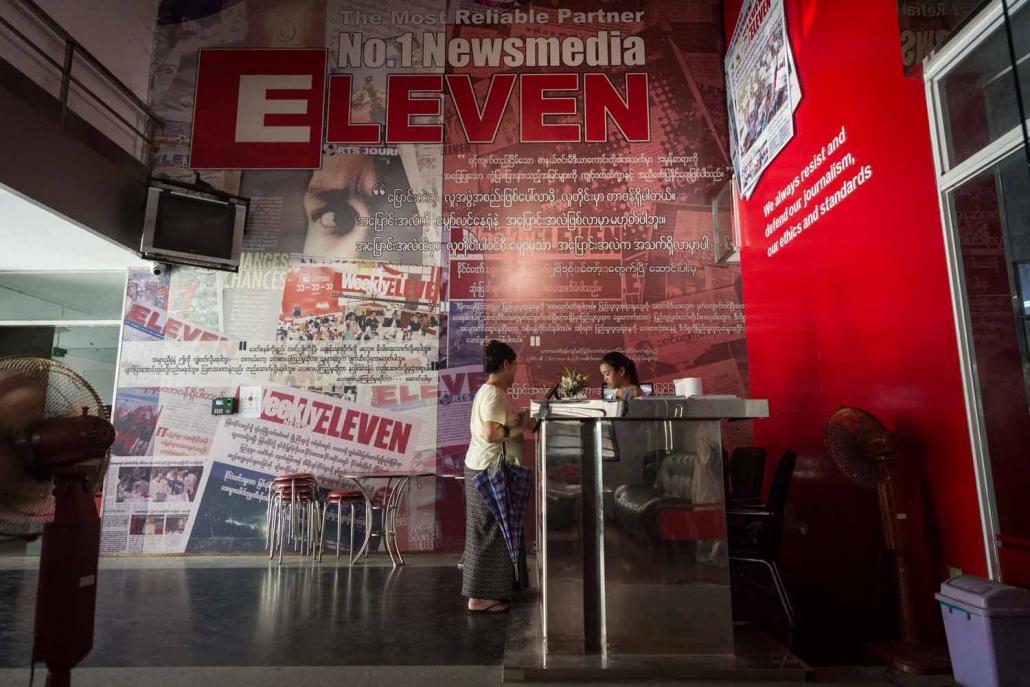

The reception area of Eleven Media Group’s offices in Tarmwe. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

It is a mindset that has certainly yielded impressive results. Circulation figures are not published in Myanmar, but by Eleven Media’s own reckoning, its daily edition and weekly journal are the most-read print publications in the country. (7Day, the only newspaper company with the potential to rival Eleven’s reach, pays less in tax but also has fewer titles.)

The company has grown exponentially since the founding of its weekly news journal in 2005, with the launch of an English-language news website in 2012 and a daily Myanmar-language edition the following year, shortly after the government abolished Myanmar’s decades-old prepublication censorship.

Eleven’s triumphs are apparent from the moment of entry to its head office – a lavish and expensively furnished seven-floor building on South Racecourse Road that swarms with more than a hundred young and eager journalists. Inside it boasts a TV studio, a private suite for Than Htut Aung and a lobby with wallpaper boasting of its status in the local market.

Even in its early years, Eleven Media pushed the limits of what was then one of the strictest censorship regimes in the world. Shortly after winning the Golden Pen of Freedom Award in 2013, the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers lauded Than Htut Aung for using First Eleven’s sports reporting to craft subversive political messages for its audience. The paper was occasionally subject to publication bans, while in 2004 its computer equipment was seized and some of its reporters briefly detained over articles that earned the ire of the junta.

After the quasi-civilian government of U Thein Sein was installed in 2011, Than Htut Aung became increasingly strident in his criticisms of Myanmar’s rulers. On November 11 of that year — coinciding with his media empire’s 11th anniversary — he held a public conference to slam the government for its continued incarceration of political prisoners.

In the audience, a number of seats were deliberately kept empty for the members of the 88 Generation, the activist network of former students who helped lead the 1988 uprising against one-party rule, many of whom had spent more than a decade of their lives behind bars in the time since.

Battles and threats

In the same year – the last under the military-era censorship regime – Eleven Media also ran a spirited campaign against the controversial China-backed Myitsone Dam, a project signed by the former junta that had quickly become a lightning rod for public discontent and protest against the country’s leaders. On both issues, Than Htut Aung proved to be on the right side of history: the Thein Sein government began a mass amnesty of political prisoners the following year, and issued a permanent suspension of work on the Myitsone project. But other battles loomed.

For much of the last government’s term, Eleven Media had a stormy relationship with Minister for Information and government spokesman U Ye Htut. Ironically, the minister had risen to prominence as a regular international affairs columnist in Weekly Eleven, but after his appointment he criticised Eleven for what he considered the group’s false reporting of the Thein Sein government.

Shortly after his appointment in 2014, Eleven accused the Ministry of Information of paying a grossly inflated price for a printing press and speculated that the purchase was tainted by corruption. Though the media group had made other claims of malfeasance against government departments without a response, the Information Ministry responded by filing a lawsuit against Eleven Media.

A man reads a copy of the Daily Eleven newspaper at a Yangon teashop. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

Rather than withdraw its claim, Eleven widened its criticism, accusing the ministry of scheming to sell off public land at a concessional rate to Skynet, a private monopoly which controls much of Myanmar’s television broadcasting spectrum.

With its own ambitions to launch a TV network, Eleven has frequently been critical of Skynet and its parent company Shwe Than Lwin, and observers have speculated that Ye Htut’s refusal to grant Eleven a broadcasting licence was a factor in hostilities between the minister and the media group. (Ye Htut did not respond to a request for comment from Frontier.)

At the same time, Eleven has not shied away from launching legal action against its own critics. One of the most outspoken members of the previous parliament, U Hla Swe, found himself on the receiving end of a defamation lawsuit after accusing Than Htut Aung of building his fortune on illegal logging in his home constituency of Gangaw during the 1990s. (The Eleven chief has maintained that his timber enterprise operated according to the law, under logging licences issued by the military regime.)

Late last year, Hla Swe was slapped with another lawsuit, this time for public obscenity, after a press conference in Yangon’s Mahabandoola Garden, during which he told an Eleven reporter that he and his colleagues were “dicks”.

The most rancorous battle between Eleven and its critics, however, has been reserved for a member of the media. Columnist Sithu Aung Myint, a regular contributor to Frontier and several other publications, has been threatened with legal action by Eleven 10 times since 2013 over claims that his work had sullied the media group’s reputation (the lawsuits that eventually made it to court were thrown out).

Frontier met with U Nay Htun Naing, Eleven’s executive editor, at the media group’s offices in March. Asked why his organisation had pursued legal action against another member of the media, Nay Htun Naing said Eleven did not want to be forced into waging a continuous war of words on its pages.

“Since most of the articles he has written were intended to be personal attacks, or insults, we don’t want to publish these personal matters in our papers,” he said. “It would be a never-ending process if he keeps writing articles, so that’s why we don’t really publish stories about him in our paper. Instead we just file a lawsuit against him. We want to stop it.”

Attacks and imprisonment

To read its own coverage of its myriad public disputes, Eleven’s editors have come to regard themselves as vigorous defenders of the public interest in the face of entrenched hostility to a free press. Nowhere is this more evident than in its breathless account of an attack on Than Htut Aung last June.

Stopped in evening traffic on U Chit Maung Road, not far from the media group’s offices, two men walked up to Than Htut Aung’s car and shot at him with slingshots and metal projectiles before escaping in a taxi. The two men were promptly arrested, but Eleven’s reporting stated that at least three other men were present and assisted in the attack – at least one of whom, they alleged, is a member of Military Affairs Security, the intelligence arm of the Myanmar Armed Forces.

The following day brought a renewed attack, both on Eleven Media and the reputation of Than Htut Aung himself. The Ministry of Information filed a suit against the Eleven CEO and 16 of his employees, alleging that its coverage of the printing press lawsuit meant it was in contempt of court. At the same time, a number of Facebook pages largely used to post pro-military propaganda began publishing photos purporting to show Than Htut Aung in the company of a woman at a KTV parlour – in Myanmar, typically an establishment which fronts for illicit sex work.

According to these accounts, the attack on Than Htut Aung was not arranged by the government, as he had alleged, but instead the result of a business dispute arising from the Eleven chief’s patronage of the KTV and a romantic liaison involving the mystery woman and her boyfriend.

These rumours have been vigorously denied in editorials written by Than Htut Aung and others, who have accused the government of running a smear campaign to discredit the media group’s reporting. (Than Htut Aung is not visible in the photos, which have since been deleted. According to Nay Htun Naing, an investigation by Eleven Media found the photos of the woman were taken from an Indonesian website.)

When the National League for Democracy government came to office in late March, many journalists hoped that further restrictions on the media would be lifted, and the combative relationship between the press and the previous administration would be a thing of the past.

“We have always been operating on our principles and we are not going to change,” Nay Htun Naing told Frontier shortly before the government was sworn in. “But under the new government we believe the press environment and press freedom will improve. It is not likely to deteriorate.”

Now, just eight months on, both Than Htut Aung and the group’s veteran chief editor, Ko Wai Phyo, are facing the prospect of three years’ imprisonment.

Earlier this month, in an editorial marking the anniversary of last year’s general election, Than Htut Aung accused Yangon Region Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein of accepting a $100,000 Patek Phillipe watch from a construction magnate, himself recently pardoned for drug trafficking offences, in exchange for the awarding of contracts on the building of the city’s corruption-plagued Southwest New City. Phyo Min Thein denied the charge in a spirited press conference, claiming the watch at the centre of the controversy was a much cheaper Rolex gifted to him by his wife.

Facing charges under section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law – which has been used with increasing frequency against political and satirical speech on social media since the government took office – neither of the men are likely to be bailed before the trial concludes. The Myanmar Press Council has urged the chief minister to withdraw the complaint so it can mediate the dispute, but proceedings were continuing at time of writing.

What could prove to be Eleven Media’s last crusade still has some way to go.

Postscript: This article originally appeared in the November 24 edition of Frontier. On November 30, the bail application lodged by Than Htut Aung and Wai Phyo was denied during a hearing at the Tarmwe Township Court. The pair have been returned to Insein Prison to await trial. Since it was enacted in 2013, not one of the dozens of people charged under the criminal defamation provisions of the Telecommunications Law have been bailed between their arrest and the conclusion of their trial. Read more here.

Top photo: Eleven Media chief executive U Than Htut Aung leaves Tarmwe courthouse. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)