Praise of Myanmar’s reform success under Thein Sein fail to note that very little has changed on the country’s periphery.

The day this edition of Frontier hits the newsstands will be the official end of President U Thein Sein’s stint in the presidential chair. As he passes the mantle to his successor, U Htin Kyaw, few would have expected to have witnessed the changes that have occurred in the country during his time in office.

In the major cities, mostly Yangon and Mandalay, the construction of new condominiums and office towers, the influx of mobile phones and cars and the record numbers of visitors – not forgetting the return of exiles – are indicators of the reforms, but the roughly 35 million Myanmar people living away from urban centres have seen little change.

None more so than in Myanmar’s seven states, where the new government, led by the National League for Democracy, still needs to overcome distrust that has festered over decades, and where people will no doubt be hoping for peace and development after years of languishing under a military government that paid them little heed.

The NLD’s resounding victory, particularly in the ethnic areas, surprised many. It was largely due to a desire for change from the military, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s nationwide appeal, and a splitting of the vote caused by the plethora of political parties formed down ethnic lines.

Despite its electoral success, the NLD does not have complete support in many of these areas. While many believe the NLD will work for the development of ethnic groups, others regard the party as one that, like the military, puts the priorities of the Burmese well above those of other ethnic nationalities.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

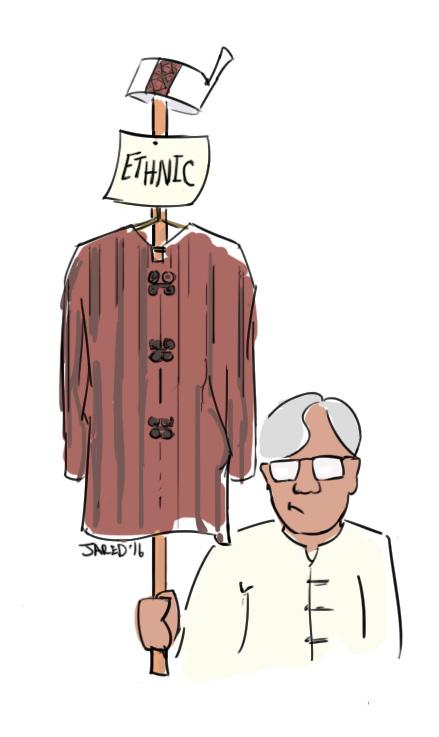

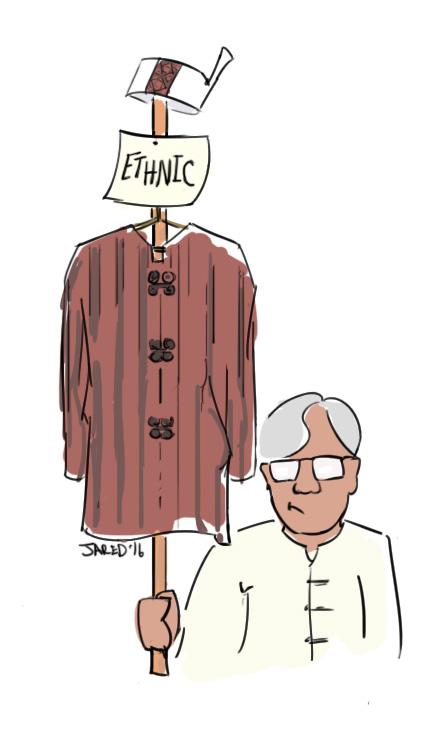

The establishment of a Ministry for Ethnic Affairs was one step in the right direction, although critics have suggested that its creation will do nothing to address the issue of federal reform and only focus on language and culture. Likewise, the nomination of ethnic Chin U Henry Van Thio as vice president pleased some, but meant little to others who see it as nothing more than box-ticking for a role that is little more than ceremonial.

More important to ethnic minorities than union-level decisions will be those made in their own states. On March 28, the NLD released the name of state and region union ministers, all of whom are party members, and some of whom are ethnic members of the states they represent.

Jared Downing / Frontier

One major concern for ethnic communities is that for too long, key decisions about what happens in their states take place far away, in the corridors of the capital, Nay Pyi Taw. It remains to be seen how much this will change under the NLD.

A Myanmar Times story on March 25, quoting NLD member U Zaw Myint Maung, who was confirmed as Mandalay Region chief minister earlier this week, said that the NLD could be planning to move some regional and state government responsibilities back to the capital – an announcement concern those calling for greater autonomy.

Many ethnic communities remain immensely distrustful of the country’s central rulers. There has perhaps been some improvement in this area over Thein Sein’s term: The National Ceasefire Agreement may not have been the huge moment the government wanted it to be, and has been cheapened by subsequent clashes, though it at least indicated some tentative, preliminary step away from the acrimony of the past. Massive challenges remain.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has said national reconciliation is one her party’s priorities. Success will only come if the non-Bamar people of Myanmar are given the right to make decisions over their own lives. In this country, political autonomy is the only difference between true reconciliation and more empty bromides.