Hundreds of students were left disappointed when the National League for Democracy government shut down a multi-million-dollar international scholarship programme set up to great fanfare in 2014.

By EAINT THET SU | FRONTIER

IN EARLY 2016, Ma Kay Khine received a letter that she thought would change her life.

An Australian university had accepted her to study for a master’s degree in civil engineering the next academic year – a degree that would be fully funded by the Myanmar government through a new programme announced in 2014.

All she needed to do now was submit the letter to the Higher Education Department, which she did on April 1, 2016, and wait for approval. “I was so excited for the next big step in my education,” Kay Khine said.

But that was when “the silence started”. She heard nothing from the department for months.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Still, she began preparing for her life abroad. Every weekend she travelled to Yangon to take preparation classes for the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), the results of which she needed to send to her university. She also bought some textbooks so she could be ready for classes in July 2016.

When she didn’t hear back from the department, she deferred her studies to February 2017. “I had confidence in our government – I thought I would definitely be going to university. I even turned down other career opportunities overseas because this scholarship was my dream,” she said.

Then, in December 2016, a representative in the Pyithu Hluttaw asked whether the government planned to support master and doctorate degree scholarship recipients – one of whom was Kay Khine – who had received offer letters from universities abroad for the 2016-2017 academic year. The lawmaker, U Bo Bo Oo (Sanchaung, NLD), said more than 50 students in line for scholarships had complained to him that they’d received “no response” from the Higher Education Department.

Deputy Minister for Education U Win Maw Tun replied that the government would “continue awarding the 43 master applicants and 22 PhD applicants … who received offer letters from the international universities”. He said it was “under arrangement” and the government planned to expand the programme and “award scholarships to lecturers in universities to improve their capacity”.

However, the following October, Win Maw Tun came back to parliament to announce the scholarship programme would be discontinued – about two years after Kay Khine had started applying to foreign universities.

For Kay Khine, it was confirmation of what she had suspected, but it was still a crushing blow. “I was so disappointed when I heard the announcement that they were not continuing the scholarships.”

Like all of the scholarship recipients interviewed for this story, Kay Khine spoke to Frontier on condition of anonymity (this is not her real name). Those publicly linked with the programme have faced abuse on social media because they were perceived to have received scholarships based on close connections to government officials rather than merit.

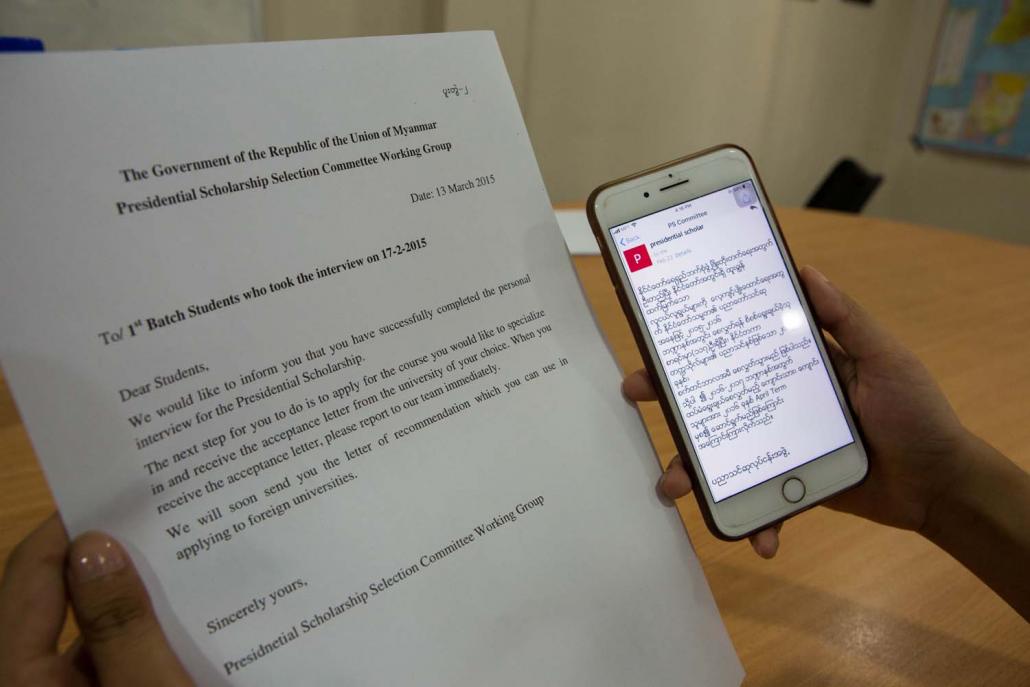

A March 2015 letter from the Presidential Scholarship Selection Committee Working Group to an applicant confirming they had been awarded a scholarship to study abroad. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Best and brightest

President U Thein Sein announced the President’s Scholarship Award in February 2014, billing it as the first such programme in five decades. The programme would enable Myanmar students to attend foreign universities “so that future generations can have long-lasting educational opportunities, and also [so recipients can] study subjects that will benefit the development of the country”, he said.

In the middle of the year the government invited applications from those wanting to take either undergraduate or postgraduate courses abroad, and set up a Presidential Scholarship Selection Committee Working Group to manage the selection process.

The scholarships, which could be for any subject and would cover the entirety of the tuition fees as well as accommodation, travel and food, were widely reported in the media at the time. Most observers praised the government for investing in the education of the country’s youth, and said the high cost – as much as US$80,000 a year per scholarship, according to government officials – would pay off in the long run.

But the eligibility criteria were narrow, particularly for undergraduates, who had to be 16 to 20 years of age and to have achieved a score above 500 on their matriculation exams or an equivalent. All recipients had to be unmarried, sign a pledge to return to Myanmar on completion of their studies and work in the civil service for twice the length of their course. Those who broke this pledge would be liable to pay three times the cost of their scholarship.

Kay Khine was among many thousands who submitted applications for the scholarships by the August 30 deadline, of whom more than 4,000 were invited to take an English proficiency test in December 2014 that was conducted in partnership with the British Council.

Fewer than 25 percent of those who took the language test were invited back for two rounds of face-to-face interviews with faculty members from Myanmar universities and the scholarship selection committee in February and March 2015.

The 873 candidates were split into three batches for these interviews; Kay Khine was in the second batch.

Those in the first two batches who passed the final interview, like Kay Khine, were told they could apply for entry to the courses of their choice overseas. Once they received an acceptance letter, they had to submit it to the Higher Education Department for a “recommendation letter” confirming they would get financial support from the government.

By September 2015, though, it seems that the annual budget for the programme had been exhausted. In an interview with The Voice, Ma Saw Sandy Swe, a scholarship recipient who never got the chance to study abroad, said that she was told late in 2015 she would have to wait until more funds were allocated at the start of the next financial year.

Kay Khine said she believed the third batch never had the chance to even complete the interview process. “After we finished our interviews, they announced that they had indefinitely postponed the interviews for the remaining candidates,” she said.

Counting the cost

Then, on March 30, 2016, the National League for Democracy took office.

It immediately disbanded all of the committees, commissions and working groups set up by the Thein Sein government, including the Presidential Scholarship Selection Committee Working Group.

The new administration also sought to cut expenses, most notably by dramatically reducing the number of ministries.

U Ko Lay Win, director general of the Ministry of Education’s Basic Education Department, said the NLD administration discontinued the scholarship programme because of the high cost of supporting students overseas.

“The cost for these students to study abroad is expensive and that’s why we stopped offering new scholarships,” he said. “We only continued funding those who were already abroad … who did not fail any classes there.”

In the end, only 117 scholarships – 45 undergraduate, 42 master and 30 PhD – were awarded. Medicine and engineering were the most popular majors, and most of the students went to Australia, the United Kingdom and China.

When he announced the end of the scholarships in October 2017, Win Maw Tun said the government was still supporting 79 students to complete their studies abroad under the programme, which had since been renamed the naing ngan daw (national) scholarship.

Daw Than Than Win, deputy director general of higher education department, said master and PhD scholarship recipients – most of whom were civil servants – completed their studies last year.

The government is still supporting 40 undergraduates, most of whom are due to finish their courses this year.

“Tuition for each student varies from major to major and the living allowance from country to country, but the average cost for a student studying medicine is $80,000 a year,” Than Than Win said.

At current exchange rates, $80,000 would be enough to pay the annual salary of 54 primary school teachers. Asked whether the scholarship programme was worthwhile, U Ko Lay Win defended the programme. “The main purpose of the scholarship was human resource building. The scholarship allowed the students to study subjects for their development at world class universities and later contribute their knowledge to the workforce in Myanmar.”

Dr Aung Tun Thet, who was a member of the scholarship selection committee, told Frontier he was disappointed the scholarships had been discontinued. “Programmes like the Presidential Scholarship need continuity and the two governments should have had communication between them about this. The lack of consistency made it difficult for passionate young students,” he said.

Lawmakers, too, have expressed frustration at the winding down of the President’s Scholarship Awards. On January 29, Amyotha Hluttaw lawmaker Daw Htu May (Arakan National Party, Rakhine-11) complained that more than 400 students had lost opportunities to pursue higher education abroad because the Ministry of Education had stopped providing scholarships since 2016-17. The country is in dire need of international standard intellectuals and the ministry’s failure was a loss to the country, Htu May said.

A report from the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Public Accounts Committee tabled in the hluttaw that day said a K15 billion budget had been allocated to enable 140 students study abroad.

Pyithu Hluttaw MP Dr Hla Moe (NLD, Aung Myay Tharzan) said the ministry should immediately draft a plan to select students for the scholarships and the process should be uncomplicated and transparent.

Dr Aung Tun Thet, who was a member of the scholarship selection committee, told Frontier he was disappointed the scholarships had been discontinued. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

A last-minute surprise

At some point along the way, the “workforce in Myanmar” came to include the private sector and not just the civil service. Although the initial requirement was that recipients return and work in the civil service for twice the length of their scholarship, it was later changed to allow them to work in the private sector.

Ko Lay Win confirmed that contracts signed by the scholarship recipients require them to work in Myanmar for three years. Only those who were government employees when they received the scholarship have to work in the civil service, he said.

He said he was unsure when the rules were changed, or who changed them. But he said it was impractical to require 19 or 20-year-old graduates to work in the civil service. “They are too young.”

Asked about the change, Aung Tun Thet said, “We wanted the scholars to be performing tasks like having diplomatic conversations with the president of the United States and such, but it turned out different … in my opinion, the scholars should serve the government.”

It seems the rules were quietly amended shortly before the first batch of scholarship recipients went abroad. Kay Khine, who never signed a contract, said she had not been informed of the change, and was still under the impression she would have had to work in the civil service upon her return.

The last-minute change seems hard to justify given that many potential applicants were likely put off by the requirement to work in the government. Model and social influencer Zun Thin Zar, who applied for a PhD scholarship, said she dropped out of the programme because she didn’t want to work in the government. “When the interviewers notified me about the working terms, I decided to discontinue my scholarship application because the service period was too long. I wanted to continue my career as a celebrity,” she said.

Frontier found one scholarship recipient working in the private sector in Yangon after completing an undergraduate degree for which the government paid tuition fees of more than $20,000 a year.

The recipient, who asked not to be identified, said the requirement to work in the civil service “only applies to the civil servants who got the scholarship. For us it is three years working in Myanmar for its development, not limited to any sector.”

Another scholarship recipient, who is still completing a degree overseas, initially told Frontier that when he returned his “work position will be up to the government”. Asked whether this had changed, he responded: “I’d rather not talk much about this part.”

While a small number of people have benefited significantly from the programme, many more had their hopes dashed by its sudden cancellation.

“I still have hard feelings about it,” said Kay Khine. “I have friends who received scholarships and were able to go, and now they have better career opportunities than me.”