February 22 marked 120 years since the birth of newly independent Burma’s third chief justice, U Myint Thein, who survived both World War II and a lengthy imprisonment under Ne Win to develop a love of poetry in later life.

By DR MYINT ZAN | FRONTIER

SOLDIER, ambassador, barrister, judge, political prisoner, poet: U Myint Thein was, without doubt, a distinguished man. Born at the dawn of the 20th century – February 22 marked the 120th anniversary of his birth – his life story tracks the trajectory of modern Burma.

U Myint Thein was also part of a remarkable family. He was one of four brothers, all of whom were noted barristers and followed unique career and life paths.

Four brothers in (the) law

U Myint Thein’s eldest brother was U Tin Tut (1895-1948), who studied at Queens’ College in Cambridge and was the first Burmese to become an Indian Civil Service officer. He served as Minister for Finance in Bogyoke Aung San’s pre-independence cabinet and accompanied him to London for negotiations on the future of Burma with the British government.

This trip resulted in the Aung San-Attlee Agreement, signed on January 27, 1947, which secured a pathway to independence the following January. U Tin Tut was not present when Aung San and other cabinet members were assassinated in July 1947, but was tragically killed the following September when a grenade was thrown into his car.

Next in the family was U Kyaw Myint (1898-1988). He was called to the Bar in 1921 and served as chair of the Special Tribunal that tried those accused of assassinating Bogyoke Aung San and his cabinet colleagues. After independence, U Kyaw Myint served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court from January 1948 to about 1950, when he resigned and practised law for at least another 25 years. U Kyaw Myint died in Rangoon in May 1988.

The youngest brother, Dr Htin Aung (1909-1978), had a career focused more on academia, and he served as rector and later vice chancellor of Rangoon University from 1946 to 1959. Known as Sayagyi (“revered teacher”), Dr Htin Aung had a penchant for acquiring degrees: in the legal field alone his earned – not honorary – degrees included a Bachelor of Laws from Cambridge, a Master of Laws from the University of London, a Doctor of Laws from the University of Dublin and a Bachelor of Civil Laws from Oxford.

Dr Htin Aung’s enthusiasm for academic pursuits was such that his brother, U Kyaw Myint, once told a nephew of Dr Htin Aung that he had “a dead uncle” (U Tin Htut), a “bad uncle” (U Myint Thein) and a “mad uncle” (Dr Htin Aung).

Soldier, diplomat, lawyer

The “bad uncle” obtained his tertiary degrees in Britain, graduating with a Master of Arts and Bachelor of Laws from Cambridge and was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn around 1925. While studying in England U Myint Thein met and later married Daw Phwar Hmee (1902-1962), who was the first Burmese woman barrister (from the Middle Temple).

U Myint Thein was not merely a lawyer, however. He served in the British Army, at the rank of colonel, according to Dr Maung Maung’s October 1957 profile in Rangoon-based magazine The Guardian. At great risk to himself, U Myint Thein stayed on in Japanese-occupied Burma, at times disguising himself as a mali (the Hindi word for “gardener”) to avoid being identified by the Japanese as a British soldier. In the 1957 article Maung Maung was full of praise for U Myint Thein – slightly ironic given events just a few years later – and noted that he “could have died” during those dangerous years of World War II.

U Myint Thein was also a diplomat. Soon after independence, he was appointed as the first Burmese ambassador to what was then Nationalist China. When the People’s Republic of China was established in October 1949, U Myint Thein was appointed as the first Burmese ambassador to the PRC.

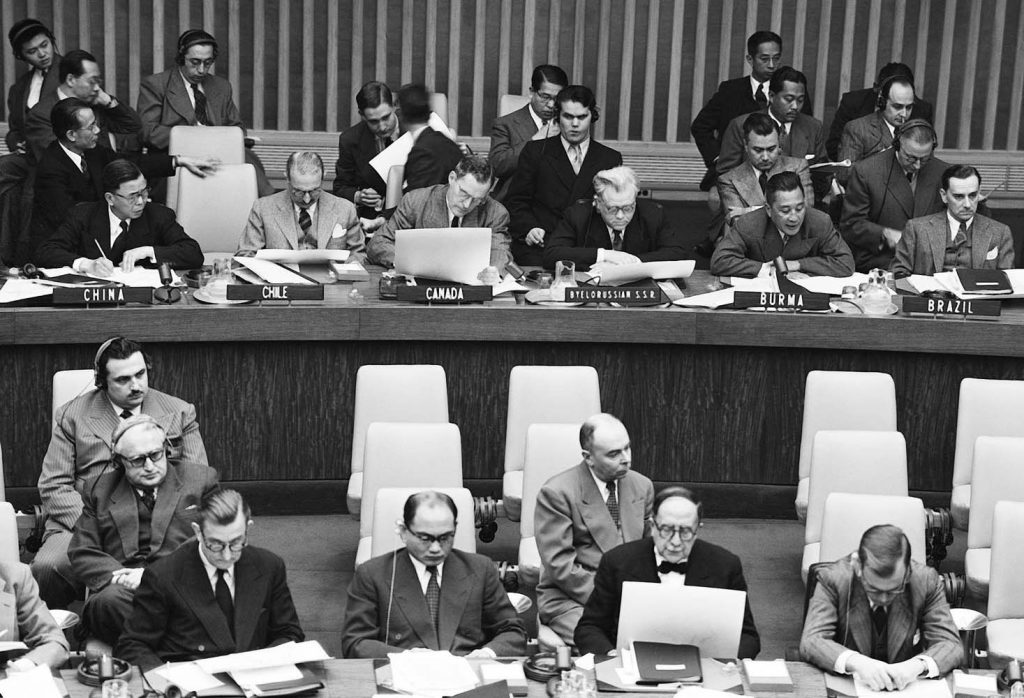

After returning to Rangoon, he was appointed as a Supreme Court justice in March 1953. Soon thereafter, U Myint Thein went to the United Nations to complain about an incursion of Kuomintang troops into Burma. Maung Maung wrote in his 1957 article that U Myint Thein’s contribution to the debates in the UN General Assembly was “brilliant … and a landmark in UN history”.

In July 1957, Burma’s president appointed U Myint Thein as the third chief justice of the Supreme Court. As chief justice, U Myint Thein wrote many rulings – a few of which are landmarks in the legal history of independent Burma.

General Ne Win strikes

In his 1957 profile, Maung Maung wrote that U Myint Thein’s life up until his appointment as chief justice had been “both lucky and unlucky”. From 1962, though, his luck took a turn for the worse. After General Ne Win took power in a military coup on March 2, soldiers entered U Myint Thein’s house at 48 Kaba Aye Pagoda Road in Rangoon at 2am.

U Myint Thein later told me that when the soldiers instructed him to like khei bar (“come with us”) he asked whether he could at least inquire “what was the matter” with the commissioner of police. The soldiers politely told him not to indulge in such an activity, since all the phone lines had been cut.

Decades later, I read that U Myint Thein had asked them for an arrest warrant. The arresting officers went to their commander, who told U Myint Thein that it was a military takeover and no arrest warrant was needed. At that time, the chief justice was the second-highest ranking state official after the president.

On March 30, 1962, Ne Win – by then chairman of the Revolutionary Council – issued an “order having the effect of law” to terminate the services of U Myint Thein and a few other Supreme Court and High Court justices with effect from noon on March 31. However, in his “order” Ne Win stated that the Justices were to receive the privileges they were entitled to. Though the word “pension” was not stated in Ne Win’s order, U Myint Thein told me that he and other justices did receive their pensions after their service was terminated.

U Myint Thein’s wife, Daw Phwar Hmee, had not been in good health and she deteriorated further after her husband’s arrest. U Myint Thein was allowed to stay with Daw Phwar Hmee in her last days only under strict guard. I learned later that in order for U Myint Thein to be allowed to be beside his wife, his older brother U Kyaw Myint had to exchange places with him in “protective custody”.

When Daw Phwar Hmee died on June 26, 1962, U Myint Thein decided not to attend her funeral and voluntarily went back to – as he described to me in 1980 – the “tender loving care” of his minders. Just a few months ago I read a reproduction of a news item in the Burmese language newspaper Kyemon (The Mirror) from late June 1962 that mentioned that U Myint Thein did not attend his wife’s funeral. Perhaps he thought that the sooner he returned to his detention, the sooner his elder brother could be released.

A partial honour

Of the top state leaders detained in the 1962 coup, U Myint Thein spent the longest time in custody. Finally, on or about February 27, 1968, U Myint Thein was released and taken to his elder brother U Kyaw Myint’s house. He had spent four years and eight months at the apex of Burma’s judiciary, and nearly six years in custody following the March 1962 coup. After his release U Myint Thein met regularly with the diplomatic corps, who dubbed him Uncle Monty – a name that would stick.

In June 1980, Naing Ngan Gone Yi (literally “jewel of the state”) awards were conferred on dozens of people, including quite a few former detainees of the Revolutionary Council regime. This included former chief justice U Myint Thein, who received the first class Naing Ngan Gone Yi award and also a “political pension” – in addition to his chief justice pension – for life. Around the same time, President Ne Win invited to dinner U Myint Thein and other apex court judges whom he had placed in detention years before.

A nephew of U Myint Thein recalled that Ne Win had tried to “explain” the Revolutionary Council’s incarceration of him after the coup, but the gentle former chief justice stopped him. “General,” he said, “it is past: we do not need to dwell on it.”

Largeness of heart and magnanimity indeed.

Myint Thein as poet

While in custody, U Myint Thein had the privilege – one of a few accorded to him in his detention – of listening to a radio. During this time he listened to Burmese folk songs broadcast by Myanma Athan (Burma Broadcasting Service), wrote them down and translated them into English. They were later published as Burmese Folk Songs.

He also published several poetry selections, including the serious and reflective When at Nights I Strive to Sleep, and the more cheery Burmese Proverbs Explained in Verse and Burmese Nursery Songs.

U Myint Thein fell seriously ill in 1983 but recovered. He later wrote to me: “Please don’t worry too much. Only good people die young and I am only 83.” He fell seriously ill again in 1989 or 1990, to the extent that the late U Aung Gyi, the former brigadier-general and National League for Democracy co-founder, apparently sat beside him and wept, stating in Burmese, thu kha myar democracy ya dar ko taung hma kyeit ma thwar ya boo – “Poor him, he does not live to see democracy take root”.

U Myint Thein narrated this story to my late mother with a chuckle – self-deprecating humour was his trademark. Time did eventually catch up with him, of course. But as I wrote in my tribute to U Myint Thein in The Australian Law Journal of March 1995, “death overtook even those who are youngest in spirit, and the ‘baddest’ and indeed the greatest and the best among us … all those who had the privilege of knowing him are impoverished by his passing”.