Some villages in central Myanmar are inhabited by the descendants of thousands of Portuguese, who were settled in the area by a kindly Taungoo dynasty king.

By MRATT KYAW THU | FRONTIER

Photos TEZA HLAING

MANY OF THE residents of a handful of villages on the vast plain in Sagaing Region between the Chindwin and Mu rivers have a special reason to celebrate the upcoming visit of Pope Francis, head of the Roman Catholic Church.

The community has been living in the area for about 400 years. Today’s villagers are the descendants of Portuguese traders and adventurers who began arriving in Burma in the early 16th century in search of their fortune.

One of the best-known Portuguese adventurers was Felipe de Brito e Nicote, who served the Rakhine king, Min Razagyi. In 1599, de Brito was made governor of Syriam, a busy port on the Bago River in what is now Yangon’s Thanlyin Township, where the ruins of the country’s first Catholic church can be seen on a hilltop.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic75.jpg

Ko Chan Nyein Zaw and his uncle sit in front of the Assumption Church at Chanthaywa. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

De Brito, who commanded a force of about 3,000 men, enraged the Burmese after his forces desecrated Buddha images and in 1613 Syriam was attacked by the Taungoo dynasty king, Anaukpetlun. De Brito was captured and executed by impaling. The Portuguese community, between 4,000 and 5,000 people, was taken prisoner and marched to the Taungoo capital, Ava. Some sources say it took them 10 weeks to complete the journey.

In 1628, Anaukpetlun was succeeded by King Thalun. He encouraged the Portuguese and their mixed-race families to integrate, and gave them the land where their ancestors live in Sagaing, in an area known as “Anya”.

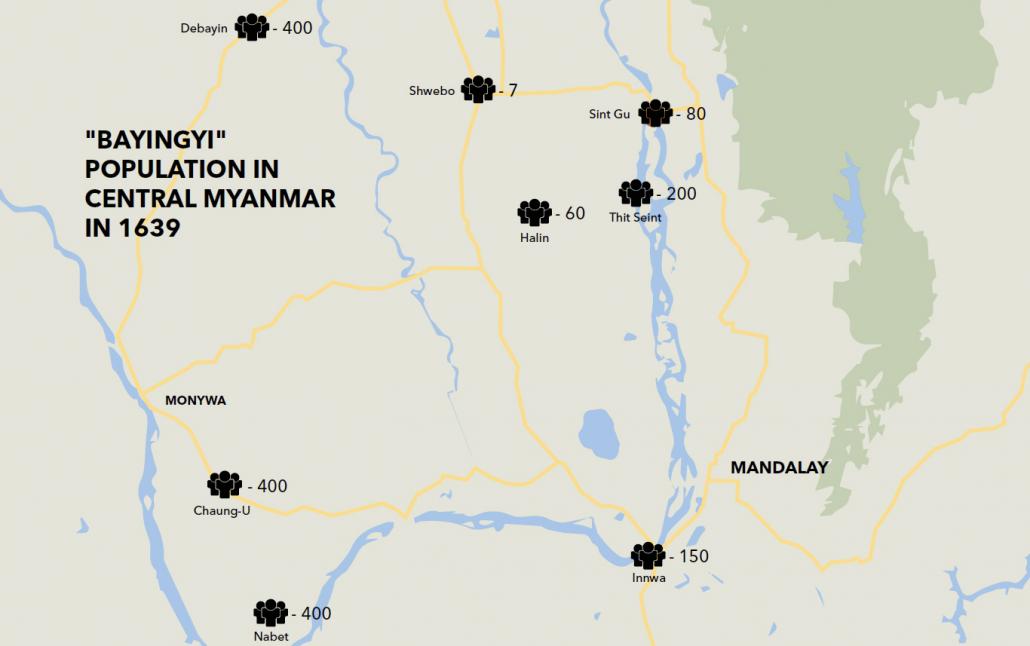

bayingyi-map.jpg

Apart from their churches, other distinctive features of the villages settled by the Portuguese include cemeteries close to the heart of their communities, a rare feature in Myanmar.

One such cemetery is in the centre of Chanthaywa village, in Sagaing’s Ye-U Township, about 10 kilometres (six miles) east of Ye-U town. There, Frontier saw adults mourning at the graves of relatives – the women veiled according to Catholic tradition – as their children played on the tombs. It is also unusual to see children playing on graves in Myanmar.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic80.jpg

A Catholic Church sits in the centre of Chaung Yoe. The Portuguese originally settled at a village named Yadana Kone Yoe before moving to Chaung Yoe in 1737. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

The Catholics also have a distinctive way of prayer. They sit on the floor like Buddhists as they hold their beads, and after praying to an image of Mary, they complete the ritual by bowing three times, in the Buddhist way.

Other big villages inhabited by descendants of the Portuguese in Sagaing are Mon Hla, Nabet, Chaung U and Chaung Yoe.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic56.jpg

Teza Hlaing | Frontier

Historians say Mon Hla, in Khin-U Township, about 22km (14 miles) east of Khin-U town, was established before the Portuguese arrived, during the Ava dynasty (1364-1555).

Mon Hla is the home village of Cardinal Charles Maung Bo, Myanmar’s first cardinal, who was installed by Pope Francis at St Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican in February 2015.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic67.jpg

Inside the Assumption Church at Chanthaywa. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Frontier travelled to the house where he grew up and met his relatives during a recent visit to the village.

Mon Hla is also the last resting place of an Italian Barnabite missionary, Father Giuseppe d’Amato, who died there in 1832 and was highly regarded for his proficiency in Sanskrit and his studies of Burmese natural history. D’Amato, who left Italy in 1782, translated some Buddhist literature into Italian and the Bible into Burmese. He was also famous for being the first foreigner to visit the ruby mines at Mogok.

Chaung U village in Monywa Township, about 22km east of the regional capital, Monywa, has existed since the Bagan era, according to history books. Nabet village is in Myaung Township, about 11km north of Myaung town.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic39.jpg

Teza Hlaing | Frontier

There are no records for when Chanthaywa was established. Chaung Yoe is the only village known to have been established when the Portuguese settled in the area. The Portuguese descendants first arrived at a village called Yadana Kone Yoe before moving to Chaung Yoe in 1737.

Chaung Yoe resident U Andrew Myint Swe, 73, said his ancestors had settled there because it had better water supply than Yadana Kone Yoe, where there’s a cemetery with ancient Portuguese graves.

The descendants of the Portuguese were once known, because of their Caucasian features, as “Bayingyi”, but the term has almost disappeared.

In a paper marking the 500th anniversary of the Catholic Church in Myanmar, which was celebrated in November 2014, Professor Dr Yaw Han Htun explained that “Bayingyi” is derived from the term used by Middle Eastern Muslims to describe the Christian invaders from Europe during the Crusades, which took place between 1095 and 1291.

“Bayingyi is derived from the Muslim term, ‘feringhi’, to describe the Christians,” he said.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic71.jpg

Teza Hlaing | Frontier

The Rev Saya Aung Nyunt wrote in 2011 book Mandalay Catholic Church and Bayingyi Villages that the term refers to Catholics living in Myanmar. “It is not a name related to race,” he wrote.

The Catholics of Anya are grateful for the land provided by the Taungoo king Thalun, who was known to have a favourable attitude towards foreigners, including Christian missionaries.

The decision to settle the Portuguese and their descendants in the area was because of the “good management” of Thalun, said Father Peter Sein Hlaing Oo, from St Joseph’s Catholic Major Seminary, (Mandalay), who has compiled a history of the Catholic church in Myanmar.

Frontier could not find any records showing how many people were moved to the Anya region.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic48.jpg

Many graves, headstones and plaques in the cemeteries at Mon Hla and Chanthaywa in Ye-U Township date from the the 18th and 19th centuries. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

In 1639, 26 years after the Portuguese were marched north from Syriam, Father Denis Atumes, a priest in the community, conducted a census of the “Bayingyi” population. He recorded 400 each living at Nabet, Chaung Oo and Depayin, 200 at Thit Seint, 150 at Innwa, 80 at Singu, 70 at Shwebo and 60 at Halin.

As well as granting land to the Portuguese and their descendants at Anya, Thalun also had members of the community serve the palace. They included Portuguese and other foreigners, who served as mercenaries because their weaponry skill was superior to that of the Burmese.

Some of the people of Anya grow paddy but they are better known for raising animals and for slaughtering them, an activity shunned by Buddhists. Most residents of Chaung Yoe are butchers and both it and Ye-U are famous throughout the country for their sausages and dried beef.

“At first, Bamar Buddhists were a bit reluctant to eat meat like beef, and there was a disdain of us from their community as we were doing butchery. But later they understood us and many people are doing butchery as business,” said Chaung Yoe resident U Simon Aung San, 60.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic72.jpg

Teza Hlaing | Frontier

As Christians, the descendants of the Portuguese suffered discrimination in the past from Bamar Buddhist officials when they applied for national identity cards.

Father John Eudes Aung Kyaw Khaing, from the Assumption Church at Chanthaywa, said that under the military regime, many residents gave up trying to acquire citizenship.

“During that time, they wanted the registration card to show their true name and their face, but they gave up because the process was complicated and they did not want to negotiate with government officials,” he told Frontier.

The officials would not allow the descendants to be identified on national registration cards as Portuguese/Bamar, and eventually the descendants acquiesced and allowed to be identified on the cards as Bamar.

tzh-bayingyi_catholic41.jpg

Teza Hlaing | Frontier

It’s much easier now for the descendants to acquire citizenship. For Chaung Yoe residents, the process involves acquiring documents from a township-level committee in Taze and then seeking its approval to verify them as native Bamar residents of the village. Once they have the recommendation, they can apply for a national ID card.

Another obstacle to citizenship was that the descendants were labelled “kalar” by the Bamar community because of their foreign ancestry.

“A long time ago, nobody was interested in applying for citizenship, and many families also didn’t have a household registration. But today, it is easier to conduct business with one, so we tried the best we can,” said Simon Aung San.

After hundreds of years, the Portuguese and mixed-race people in Anya have successfully assimilated into Bamar culture. For example, many young people do not remember their Catholic birth and confirmation names and they address each other in the same way as other as other citizens.

“We are all now Bamar on our identity cards,” said U Peter Chan Myae Zaw, 32, from Chanthaywa.