Thailand’s DTAC, which is majority-owned by Telenor, is trying to tap into the Myanmar migrant market.

By PETER JANSSEN | FRONTIER

Teng, a 21-year-old Myanmar housemaid working in Bangkok, calls her home in Kayin State at least once a month to talk to her father and sisters. The phone call costs her about 100 baht (about K3,000) for an hour of chatting under a special promotion package offered by Happy Myanmar, a Myanmar-language platform owned by DTAC, the second largest mobile phone operator in Thailand.

While most of the Myanmar nationals working in Thailand constitute an underclass of labourers doing the menial jobs shunned nowadays by Thais, for Thai telecom operators they are prime customers.

“Actually Myanmar people are high-revenue customers, very high,” said Supavas Prohritak, Vice President of Total Access Communications (DTAC).

DTAC started to seriously target the Myanmar market in Thailand back in 2012 with the launch of its Happy Myanmar platform, making it the first Thai telecom operator to recognise the growth potential of the millions of Myanmar nationals working and living in the kingdom.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“We were the first operator to tap into this segment because we saw the fast growth of the population,” Supavas told Frontier.

Estimates of the documented and undocumented Myanmar population in Thailand range between 3 and 5 million. DTAC’s own estimate is closer to 5 million, based on their projections from SIM card usage, although the company does not disclose the exact number of Myanmar SIM holders among its 25.5 million subscribers. Thailand’s total number of SIM card users is close to 82 million, considerably above the 65 million population. The leading telecom operator is Advanced Info Service (AIS) while the third largest is TRUE, after DTAC.

TRUE also offers a Myanmar language platform but DTAC’s Happy Myanmar is now well established among the Myanmar overseas community, of which it claims to have captured 70 percent of the market. “My friends told me to get DTAC because it was cheaper than the others and they offer a lot of good promotions,” said Teng, who bought her first DTAC SIM card three years ago.

DTAC has fought hard for its market share. When it first started pushing Happy Myanmar in 2012 it offered low prices on local calls, such as a “Super Mouth” package that allowed users to chat on the phone all day for only 12 baht.

As smartphones gained in popularity, DTAC added applications to Happy Myanmar like Facebook and LINE, along with services such as Thai language study and the latest lottery results. Later it introduced International Direct Dialling and finally a money transfer service.

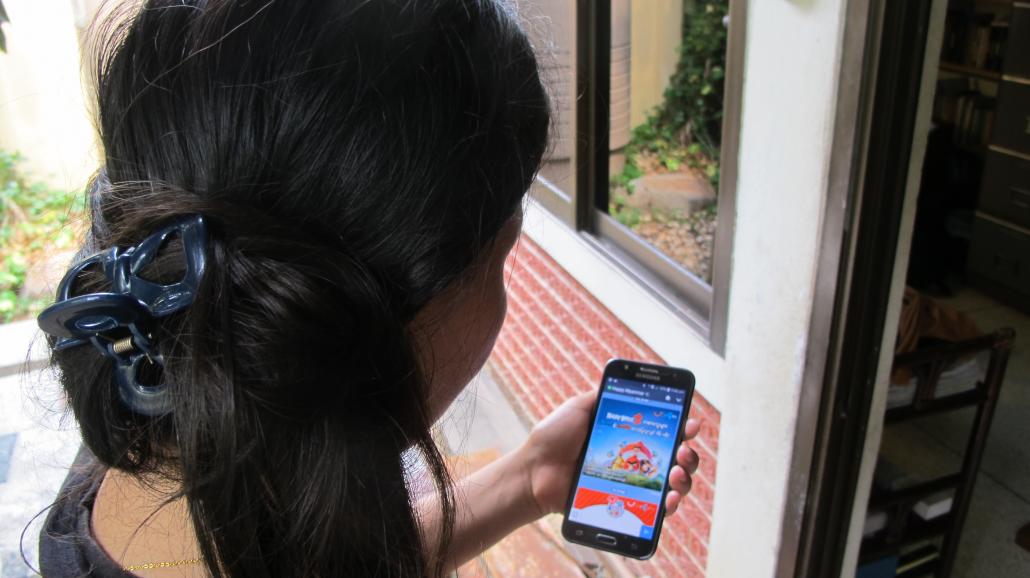

A user in Bangkok demonstrates DTAC’s Happy Myanmar service. (Peter Janssen / Frontier)

“Most of our revenue comes from air time business but IDD accounts for a big proportion of it,” Supavas said. DTAC is banking on people like Teng calling her home in Myanmar once a month. An IDD call on the Happy Myanmar platform normally costs 3 baht a minute, about a baht cheaper than what AIS charges, but six times more than the 50 satang (just over $0.01) DTAC charges for local Thai calls. This is the main reason that DTAC’s Myanmar customers are valued.

“The Myanmar market is more profitable because the IDD provides a good margin since normally they are calling within the DTAC network,” Supavas explained. “So we don’t need to pay the inter-connection charge, because if DTAC calls AIS we have to pay AIS some money.”

Many of the IDD calls made to Myanmar from Thailand are actually within the DTAC network because DTAC is also popular in the Myanmar states bordering Thailand, such as Kayin and Shan states. “Everyone uses DTAC in Kayin State because their relatives are in Thailand, not in Yangon,” Teng said.

DTAC, which is majority owned by Telenor, is hoping to further exploit its Myanmar connection through the Norwegian telecom giant’s growing regional network. Telenor Myanmar was one of two foreign telecommunication companies to win licenses in 2014 to operate mobile phone systems in Myanmar. It is currently the second largest mobile phone operator in Myanmar, with about 15.5 million users.

“What DTAC has that is special is Telenor Myanmar. The other two operators in Thailand don’t have a sister company. So what we need to do is to improve our cooperation between DTAC and Telenor. That is our next step,” Supavas said.

DTAC would like to use the Telenor Myanmar network to hook Myanmar nationals up with a DTAC’s Happy Myanmar platform even before they cross the border in search of employment. And by keeping IDD calls within the Telenor network they could either boost margins or reduce prices. “This is our ambition.”

DTAC’s main competition is arguably not other telecom operators but rather new technologies, which are making old-fashioned IDD calls an unnecessary expense. “Nowadays Burmese people in Thailand, whether they are migrant workers, activists or academics, are using less costly methods such as Facebook Messenger, Viber or LINE to communicate with friends and relatives in Burma,” said U Soe Aung, a long time Thailand resident and spokesman for the Forum for Democracy in Burma.

“These days the Internet in Burma is not as bad as before, so you can communicate on Facebook Messenger, or Viber, or LINE which is more popular in Thailand,” he said. “And they are free. I don’t know how many Burmese are still using telephone operators such as DTAC, AIS or TRUE.”

In fact, according to industry statistics compiled by the main Thai mobile phone operators, subscriber numbers declined last year for the first time in a decade of steady growth, from 98 million in 2014 to 82 million in 2015. In the same period, Internet users jumped from 29 million in 2014 to 40 million.

The shift may be ominous for the mobile phone business on a whole that is still heavily dependent on people using phones to make phone calls. “Whatever we have done can be copied on the computer right away, so we need to find something that can’t be copied,” Supavas said.

“Everyone can offer local calls, so the one unique selling point for us will be IDD. That is our only selling point.” And the most lucrative market is the Myanmar market which, while it may be able to use free applications to contact friends in the big cities, will still need IDD to contact relatives in the remote hinterlands where many migrant workers hail from.