Spectacular displays of acrobatic skill enthral audiences during the annual chinlone festival held at the Maha Muni Pagoda in Mandalay in the two months leading to the end of Waso.

Words & photos IVAN OGILVIE | FRONTIER

THE SCENE is distinctly Burmese and the atmosphere electrifying. Men puff cheroots and pause occasionally to spit betel juice into buckets, while senior monks sit in a VIP section at the front. The venue is within the sprawling compound of the Maha Muni Pagoda in Mandalay.

The occasion is a chinlone festival held annually in the two months leading to the end of the Myanmar month of Waso, which this year fell on the full moon day of July 16. The crowd is pressed to the line of the circular court and every person is transfixed by the action in the centre of the new stadium, which has replaced a teak building that was the festival’s venue for more than 100 years.

Chinlone is perhaps better described as a performance rather than a sport. It involves six players who execute spectacular acrobatic manoeuvres as they move around the court while trying to keep a small cane ball known as a chinlone in the air for as long as possible, using only their feet, knees and head. Players take turns moving to the middle of the circle where they display their best skills while teammates ensure the chinlone is kept in play. A different team performs every 30 minutes from 9am to midnight during the festival, which attracts about 1,800 teams from throughout the country.

typeof=

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The festival culminates on the full moon day – which marks the start of the three-month period known as Wardwin – with performances from the finest teams before a packed stadium.

A traditional sporting event it is not. There are no entry tickets or security. The area outside the stadium jams with motorbikes, and spectators come and go as they please. Players push through the crowd as teams pass each other to or from the changing rooms. There is no break in play all day.

typeof=

There is no winner at the end of this two-month showcase of the finest in freestyle chinlone; the performances are in fact an offering. Each team pays an entry fee to the pagoda in exchange for the opportunity for players to demonstrate their skills and gain appreciation from the crowd, from which they can acquire prestige, and, in turn, private bookings.

Chinlone translates literally into English as “cane ball” and dates back at least 1,500 years. Myanmar often dominates regional chinlone competitions. Although football is popular in Myanmar it is not that widely played by adults; in contrast, circles of chinlone players are ubiquitous.

typeof=

I became interested in the sport when I moved to Myanmar in 2015. My companion and guide at the Mandalay event was U Maung Maung, 62, a decorated veteran of chinlone who began playing at 11, turned professional at 17, played for 11 years in the northern capital’s Division 1, has won gold at international competitions, and is regarded as an ambassador of the sport. He is a renowned teacher and both his sons are chinlone champions.

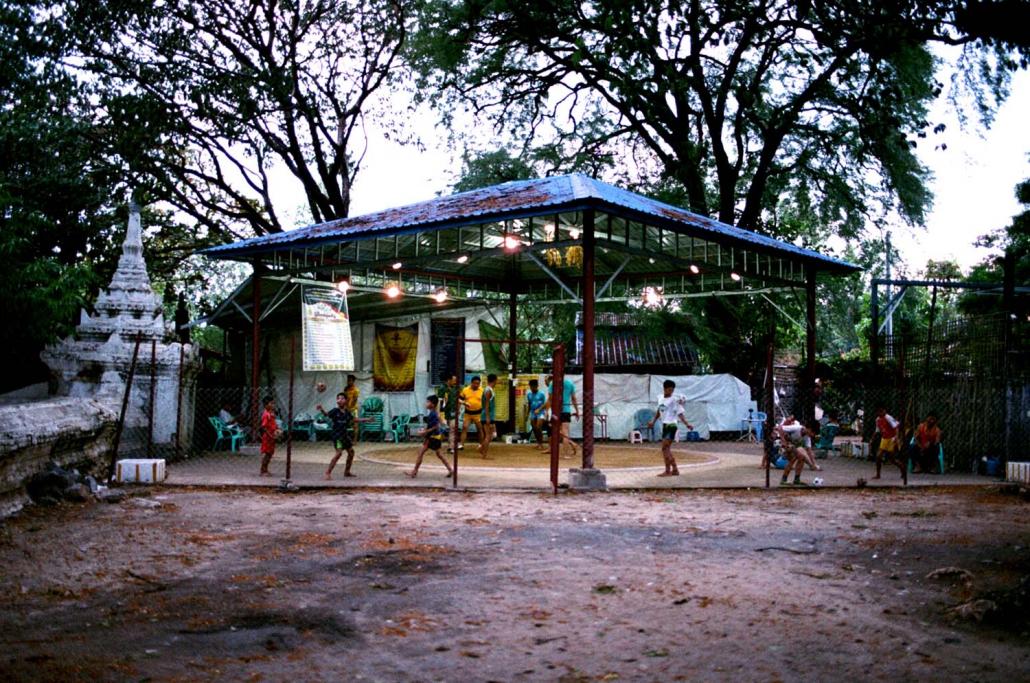

He teaches chinlone at his school, in the courtyard of a small pagoda, just a short walk from his home. Learning can be tough and repetitive as the six basic moves are practised repeatedly until they are mastered. Kids start young and it can be years before they even get into the practice circle.

Decorated chinlone veteran U Maung Maung, who began playing at 11 and turned professional at 17.

One of Maung Maung’s students is Ko Thiha Naing, 20, who is regarded as a prodigy and clearly destined for fame. His shy demeanour contrasts with his acrobatic style on the court. Thiha Naing describes the sport in poetic terms. “Chinlone is like a vast ocean; there is so much to learn. You will never reach the end and must appreciate its beauty,” he says.

I watch Maung Maung’s team perform at the festival in a performance that begins at 2pm. Maung Maung plays with his son, Aung Soe Moe, his prodigy Thiha Naing, and Thiha Naing’s father, as well as two other students.

typeof=

Maung Maung is too old to perform acrobatically, but his timing and movement are impressive and it is easy to see why he is held in high regard. Thiha Naing plays with an abundance of energy as he keeps the ball airborne, while, the older, Aung Soe Moe has a more delicate, intricate style. He plays with a smile on his face, like a man who knows he has already cemented his reputation.

As I watch more games over the next three days, the standards improve and the crowd swells. The auspicious full moon day is the biggest of the festival and features the finest teams. Aung Soe Moe and Thiha Naing perform in the headline 10.30pm slot with players I have not seen before. The standard is awesome, the skill of each player astonishing.

typeof=

Each 30-minute pwe, or performance, begins with the players pushing through and then bowing to the crowd. A bell is sounded at 20 minutes when the game becomes more intense. The spectacle is accompanied by the frenzied music from two traditional saing waing orchestras, as a commentator describes the various trick plays.

At the 25-minute bell, the play becomes faster. The players try the most difficult moves, adding to the excitement. Members of the audience reward the best moves by walking on to the court and pinning money to the back of the players’ jerseys. Aung Soe Moe, a local boy and crowd favourite, has multiple notes pinned to the back of his jersey. Style is king.

typeof=

Regardless of how the ball comes at the players, there always seems to be a way to keep it off the ground. This, of course, comes from years of practice. Behind their backs, over their head, their bodies seem to move in ways that seem unnatural, yet graceful. Chinlone requires a deftness of touch and a quick mind.

As we watch, Maung Maung is welcoming and unfazed by either my questions or camera. His dedication to the game is obvious. “Chinlone has been my life; it has given me everything and now I teach to give something back,” he says.