Myanmar should rethink its electrification plan to acknowledge the worldwide growth of personal energy, which could make traditional grid connections redundant in some areas.

By DAVID FULLBROOK | FRONTIER

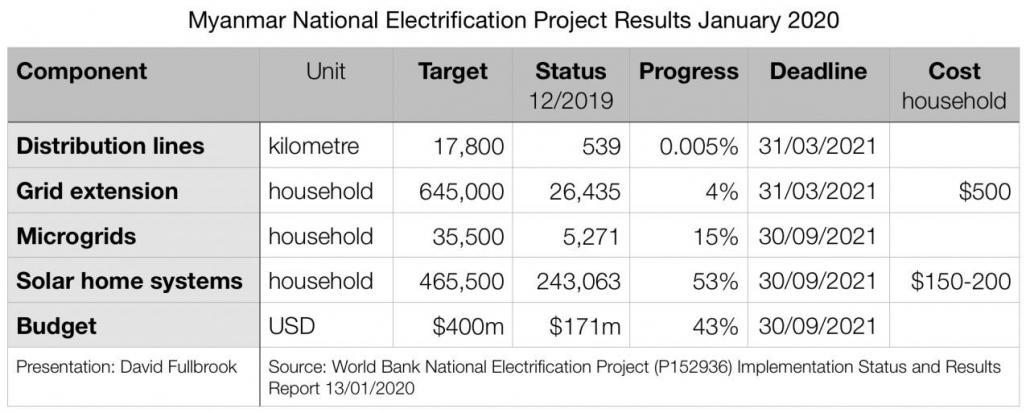

The task of electrifying Myanmar is proving hard. Recent data shows that the Ministry of Electricity and Energy’s National Electrification Project, funded through a US$400 million World Bank loan, is likely to miss many of its targets when phase one wraps up in 2021.

Although disappointing, these results hold important lessons for capitalising on advances in technology to rapidly accelerate access to electricity.

The project began in late 2015, with the goal of universal access to electricity connections by 2030. At that time, between 50 percent and 70pc of Myanmar’s 52 million people lacked an electricity connection.

The goal of phase one of the electrification project is to provide household electricity connections for 5.67 million people, through a combination of distribution lines, grid extension, microgrids and solar home systems. After four years, the project has reached 1.5 million people.

Progress on the different components of the National Electrification Project has been strikingly uneven (see table). Solar home systems, for instance, have reached half of the 2021 goal. This is three times better than for microgrids, which in turn is four times better than for grid extension. Distribution lines, meanwhile, have not even reached 1pc of the 2021 goal. Or put another way, solar home systems are connecting households 13 times faster than grid extension.

db2e7cfb-040e-49ef-a7c9-04811f7ecaae.jpg

/></p><p>The task of ensuring there are enough power plants and high-voltage transmission to increase electricity supply for households connecting to the central grid lies with other projects backed by the Asian Development Bank.</p><p>One way to read the National Electrification Project is as an experiment pitting 21st century, silicon-based solar home systems against the 19th century grid concept. In terms of speed and reliability, solar homes systems are the clear winner, echoing global trends in energy, electronics and information.</p><p>The success of solar home systems is due to their simplicity. They come in a kit comprising a 50 to 100-watt solar module for generating electricity, a battery, a few lamps and low voltage sockets. These standardised components are mass-made in factories and shipped in a box ready for use.</p><p>Solar home systems give households plug-and-play electricity. That is a radical alternative to the conventional model of waiting for dozens of departments to coordinate budgets, materials and technicians to build distribution lines and install grid connections. The complexity of this process is illustrated by the lack of progress towards the grid-focused targets of the National Electrification Project.</p><p>Moreover, even once installed, a grid connection will only supply sufficient electricity reliably if there are adequate distribution lines and grid maintenance, plus parallel projects to develop utility-scale power plants. As existing grid consumers know, in Myanmar that too has proven challenging.</p><p>The relative success of solar home systems in Myanmar is an example of the worldwide personal energy revolution, which is at a stage comparable to the late 1970s or early 1980s for the personal computer. Elsewhere in the world, families and firms are plastering the roof of their house or factory with solar modules, tailoring personal energy systems built with generic components to meet their needs.</p><p>In Africa, personal energy is booming, powered by innovative business models. Such are the opportunities that during the past decade investors, including global energy firms like Engie and Total, have poured more than $1.5 billion into personal energy in developing countries.</p><p>Rapidly advancing technology for personal energy points to a time when many households and small firms will disconnect from grids because it will be cheaper to produce all their electricity themselves. It is already happening in parts of Australia and the United States.</p><p>For that reason, many households in Myanmar may never need conventional grids. Unlike earlier models, the latest generation solar home systems, supplied by firms like Fenix, Fosera and Zola, are designed for upgrading. Consumers can add more solar panels and batteries to meet growing energy needs, from ultra-efficient fridges to electric motorcycles.</p><p>Networked personal energy is also emerging. Neighbours connect solar home systems or generic solar panels to form local grids that allow them to share energy using a novel smart controller innovated by Cambodian company Okra Solar. InfraCo Asia’s Philippines Smart Solar Network is scaling up use of the Okra controller to connect solar panels on family rooftops. </p><p>If the desired outcome is access to electricity, rather than deployment of a particular technology, the evidence points in a clear direction: towards expanding the role of upgradable solar home systems compatible with networked smart controllers.</p><p>The success of solar home systems in terms of actually providing electricity, not just a connection, does not mean the end of grid extension and microgrids, however. In a country with a sufficient level of institutional and technical capability to build power systems, such as Thailand, they still make sense in most contexts.</p><p>And, although there’s likely to be some additional delays due to COVID-19, progress towards those National Electrification Project targets might improve. The World Bank expects another 38 microgrids will be commissioned by July 2020, joining 35 already operational. Grid extension contracts for connections in a further 4,700 villages are due by the end of 2020. Even if all households in those villages are connected by 2021, it’s unclear whether they will receive a reliable supply of electricity given that a struggling grid frequently suffers voltage drops and blackouts. </p><p>Meanwhile, there has clearly been a global shift towards modular, mass-made personal energy technology like solar home systems. This poses a challenge for grids and power utility companies, because they will increasingly be competing for customers with personal energy.</p><p>This trend also presents risks for both investors and policymakers. Projecting grid extension or microgrid demand using historical data from a time when personal energy didn’t exist can be misleading. Consequently, too much grid could be built in the wrong places.</p><p>To reduce risk and hasten universal electricity access, Myanmar should rebalance its energy strategy in two ways.</p><p>Where demand density is low, such as villages and rural towns, it should prioritise personal energy. More people will receive electricity faster and the risk of premature grid extension without sufficient supply can be mitigated. This approach will also ease stress on the grid by reducing new customers. </p><p>Next, Myanmar should sharply focus the expansion and upgrading of grids and microgrids in places where demand is dense and economic output greatest, such as central Yangon and emerging industrial zones across the country.</p><p>Now is the time for Myanmar to make this strategic shift. If done properly, the country can align with global technology trends, attract more private investment and, most importantly, improve prospects for universal electricity access by 2030 – or maybe even 2025. </p></body>