A handful of tourism projects around the country are seeking to deliver real benefits to host communities, but national-level policies are still heavily focused on regulations that act as a barrier to entry for smaller operators.

By JAKOB KREMBZOW | FRONTIER

QUESTION: Which tourism destination is already fully booked for the whole of next year? It’s not Bagan, with its thousands of temples. And it’s not Inle Lake, with its unique leg-rowing fishermen.

Not many would have identified four humble villages in Myaing Township, Magway Region. But a community-based tourism project initiated by ActionAid Myanmar has transformed this sleepy area of the dry zone into a highly rated stop on Myanmar’s tourist trail.

Mr Lee Sheridan, general manager of Journeys Adventure Travel, said his company plans to send about 1000 guests to the four communities in Myaing throughout the coming year. A project to help develop the villages was initially launched by ActionAid, a British NGO, several years ago, and Journeys Adventure Travel came on board in 2015 help develop the tourism component of the program.

Community-based tourism encompasses several aims. It should be inclusive, delivering some of the revenues to residents in the area where the tourism activity takes place. But it also tries to the create something Sheridan describes as “experience-rich travel” – providing a unique, memorable experience for tourists.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

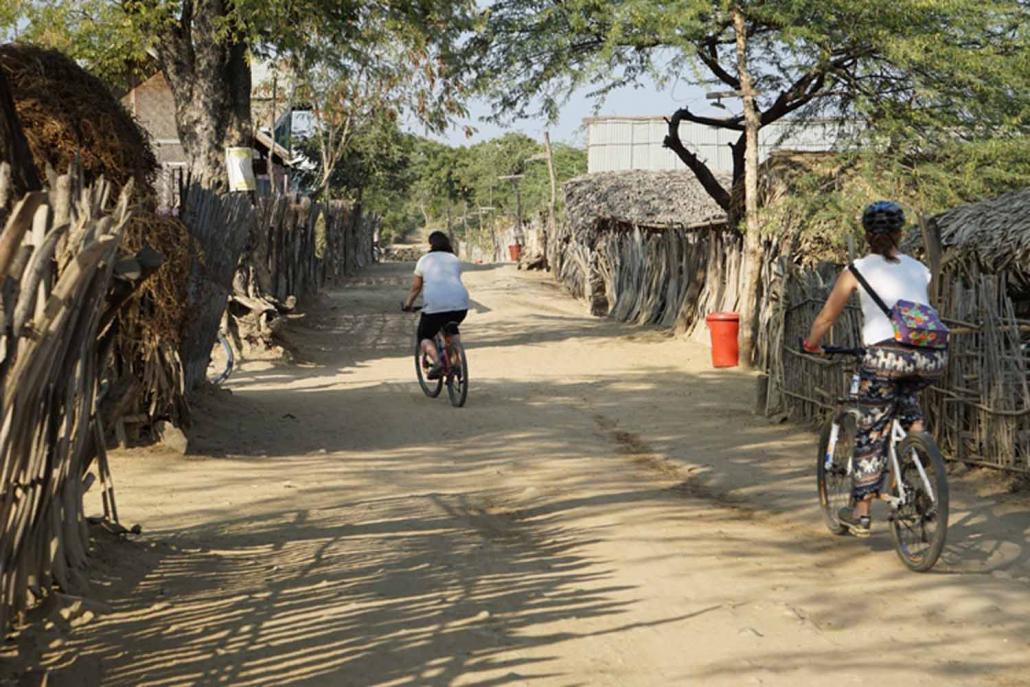

Tourists participating in a community-based tourism project ride bicycles through a Myaing Township village. (Supplied)

At Myaing, visitors spend one day and one night in the community, eating with the families and watching performances from a local group. The host households are paid for the meal they provide visitors. Besides this direct payment, Journeys pay US$10 per person to a community development fund, which is managed by the residents.

Daw Nan Khin Hmwe is the head of a women’s advisory group in Kan Gyi Taw West, one of the four participating villages. The group has played an active role in the project, and she is enthusiastic about the benefits it has brought. “It’s not only for one [person], but for all members of the community,” she told Frontier during a recent visit.

Even those who don’t spend much time with the tourists seem pleased. Resident Daw Ma Thint Lay said the project had delivered funds for a range of community projects: most recently, a new library.

The project has also received international recognition; last month, it received second place in the sustainable category of an awards program run by German magazine Travel One.

Visitors to Myaing Township are encouraged to help out with a community greening project. (Supplied)

Although the project has not yet been through a full high season, which in Myanmar runs from October to April, the feedback from travellers so far has been outstanding, Sheridan said. Most visitors are on a multiple-week tour of Myanmar, and at the end of their trip they describe spending the night in a small village in Myanmar’s central dry zone as one of, if not the, highlight.

The project remains tightly controlled by ActionAid and Journeys Adventure Travel. To ensure the incoming tourist money does not get viewed as a substitute for farming income, Journeys works with ActionAid to ensure tourism numbers are restricted to sustainable levels.

It’s expected that after the two-year period the communities will be able to manage much of the project themselves. Sheridan said he hoped that this did not result in the villages becoming heavily dependent on tourism, as it could damage their social structures and also undermine the quality of the experience for tourists.

Tourists visit a thanakha plantation in Myaing Township before having some of the tree’s bark paste – a traditional cosmetic – applied to their face. (Supplied)

The Myaing example is relatively rare in Myanmar, which has an otherwise not-so-proud history of community involvement in tourism. The industry has in the past more often served the needs of the military government and wealthy individuals.

Over the years there have been countless examples of land confiscations – particularly at beach destinations such as Ngapali, Ngwe Saung and Chaung Tha – and inappropriate and insensitive development, such as at Bagan and Inle Lake. Area residents have typically only had access to menial jobs at tourism sites, such as construction and cleaning hotels.

In an effort to avoid some of the mistakes of the past, the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism launched a Responsible Tourism Policy in 2012, which was drafted after consultations with a wide range of stakeholders.

It commits the government to community involvement in decision-making and earnings, and ensuring cultural and environmental preservation. This was followed in 2013 by the Community Involvement in Tourism Policy and Tourism Master Plan, which also touched on the issue.

In the intervening years, the industry has grown strongly, largely thanks to Myanmar’s political reforms. Tourist numbers have taken off, although they are inflated by the inclusion of day-trippers in border areas. Many new hotels and other tourism-related businesses have opened to cater to the increased demand.

There is a widespread consensus that the tourism sector will grow for the years to come. At a Tourism and Hospitality Conference in Yangon in early August, Victor Pang, the vice president of AccorHotels, declared, “This country will be a leading country in tourism in Southeast Asia.” While not everybody at the conference shared his confidence, the general expectation that tourism will grow is not really contested.

Visitors to the Myaing tourism project watch a dance performance. (Supplied)

The question is where most of the benefits from this growth will flow, and how widely they will be felt. Ms Nicole Haeusler, a rest, said the Tourism Master Plan offers a pathway to ensuring that a broad cross-section of society enjoys the fruits of tourism.

The problem, she said, is that little effort has been made to implement the proposed action in the master plan, which covers the period 2013 to 2020.

Projects like the one in Myaing are valuable, she told Frontier, but have a limited impact as they tend to operate in isolation. They do not ensure at a national level that the profits of tourism are well distributed. Nor do they ensure that the potential negative impacts of tourism are minimised.

Measures that would help achieve these goals include environmental and social impact assessments for tourism infrastructure, promotion of green technology and environmental awareness training, and regional-level destination management plans, Haeusler said.

She recommends that the ministry in Nay Pyi Taw loosen its grip on planning, instead allowing the state and region governments to develop their own strategies. However, she cautioned that training would need to be offered to support this approach.

Asked about what steps the ministry is taking to ensure the benefits of tourism are spread evenly, director general U Tint Thwin suggested that the ministry did not think it was an important issue at this stage.

Photo supplied

He said the industry should be focused on growth and consolidation, and suggested branding was the key challenge for now.

For many small entrepreneurs, the cost of establishing a business and getting the necessary permits from the ministry remains a significant burden.

But it’s not just the cost – it can also take a long time. Mr Achim Munz, Myanmar country director of the Hanns Seidel Foundation, said those wanting to open a guesthouse can be forced to wait up to two years for a licence. He added that the ministry needed to do more to create an attractive business climate for small enterprises – not only guesthouses, but also restaurants, rental shops and so on. Access to finance is also a major challenge, he said.

There are a few places around the country that offer hope for a fairer tourism economy. Another bright spot is Thandaunggyi, where the Kayin State government has introduced a pilot project for the licensing of bed and breakfast (B&B) accommodation.

Since the licences were first offered in late 2015, at least seven properties have since opened their doors to foreign guests, and all are owned and operated by members of the Thandaunggyi community.

This article originally appeared as part of Discover Myanmar, Frontier’s special report on the tourism industry. Top photo: Visitors to Myaing learn about the importance of agriculture to the area’s economy. (Supplied)