As Myanmar experiences a construction boom, those who are building the country’s new structures have few protections if something goes wrong.

Words & Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE | FRONTIER

WALK PAST almost any construction site in Myanmar and there’s a good chance you’ll witness a safety standard not being adhered to; a jackhammer being drilled into the pavement inches from a worker’s flip-flop-clad feet, or a construction worker a few dozen feet off the ground attaching their safety clip to a flimsy piece of scaffolding that looks like it could barely hold the person’s weight.

These sights are so common they have almost become the norm in Myanmar.

“I don’t like wearing this,” said Ko Aung Win, pointing to the safety helmet he had been wearing before taking a break from work in Yangon’s sweltering heat. “It is really heavy and gives me a headache. The weather is so hot and makes me sweaty and dehydrated, but I have to wear it,” he said.

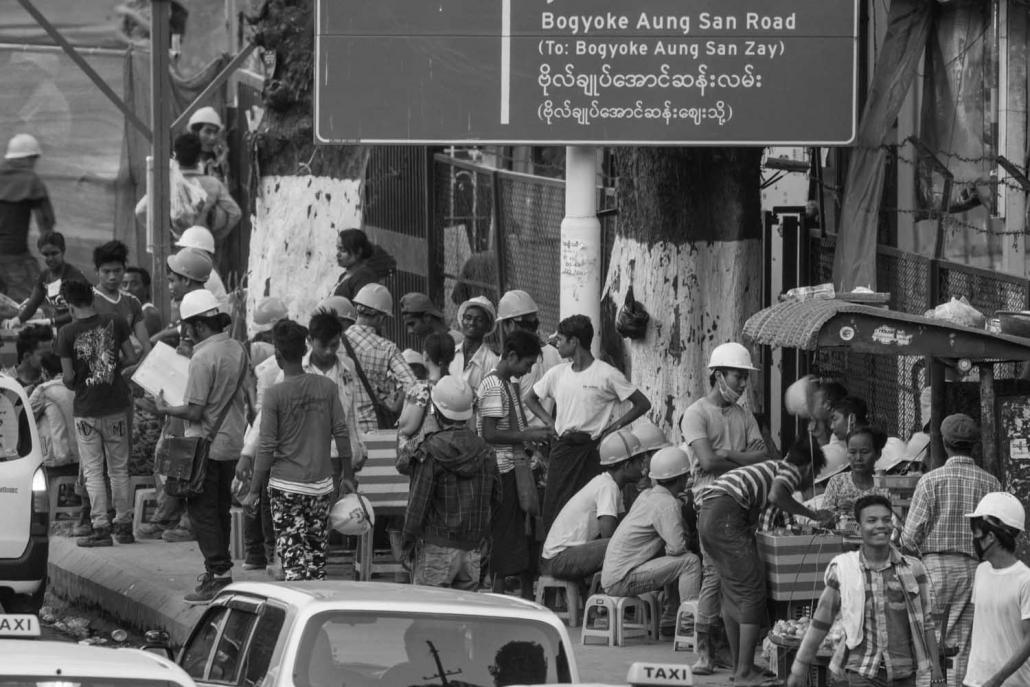

Safety standards vary significantly at Yangon construction sites. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Ko Htin Aye also works in Yangon’s construction industry. He previously worked on the construction of many of the high-rise buildings sprouting up in Bangkok, the Thai capital, where safety standards were higher, he said.

“When I worked in Bangkok they cut a third of our salary if we didn’t wear a safety suit,” said Htin Aye. “We didn’t get much money for our work, so if we didn’t wear our suit we got almost zero. We only wore it to make money – not for safety.”

Many of the construction workers interviewed for this article, whose names have been changed to protect their identity, said deaths and serious injuries had occurred the projects they had worked on.

“I have no idea how they solve the problems,” said one Yangon construction worker. “Maybe they give them money or send them to hospital or something.”

typeof=

Incidents of construction workers being seriously injured or killed are common. In one of the most high profile cases in recent years, two construction workers were killed and dozens injured when scaffolding collapsed at a hotel construction site in Mandalay in June 2015. In September last year, a 20-year-old construction worker died after falling from the third floor at a building site in Yangon’s Insein Township.

Laws protecting workers are severely outdated, critics say, with workplace safety rules currently covered by the 1951 Factory Act. In 2012, government began discussing a draft “Health and Safety Workplace” law but it has not yet been submitted to parliament.

U Kyaw Win Aung, chief mason on a construction site in Mandalay, said that almost none of the workers he knew had any form of insurance in case a serious incident happened.

“If anything happens to our health, there is nobody available to pay for it,” he said.

typeof=

Due to the lack of a legal framework, one of the major issues is that procedures relating to worker safety are left to individual businesses. Few construction companies have insurance for their workers; some pay the workers if an incident occurs. Due to the casual nature of much of the work, though, some companies refuse to pay anything at all.

Ko Thura Aung used to work as a plumber in Malaysia, where he said he earned about K900,000 per month.

“But even that’s a small amount in Malaysia. In Malaysia, if local workers get K1.5 million a month, Myanmar workers can only get K900,000,” he said.

Most construction companies do not take out insurance for their staff. Some – but not all – pay compensation to the worker in case of an accident, or to their relatives if they are killed. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Myanmar labourers earning less while working abroad is an issue, but the situation isn’t better when they return home. Many complain that they earn less than those who have been brought in from abroad.

Ko Swe Win, a worker at a large construction site in Yangon said that local workers earn about K10,000 per day, while foreign workers earn five times that.

“That’s not fair. Wherever we go, our salaries are always low,” he said.

typeof=

U Tin Maung, managing director at Capital Construction, defended the practice of paying foreign workers more, saying it was because they are “very skilful”.

“They are fast and work on time. But Myanmar workers are always late. For instance, our working routine starts at 8.30am, but they don’t arrive on time. They eat their breakfast, drink coffee and come to work at 9am. Even though [foreign construction workers] are more expensive, it is worth it,” he said.

typeof=

Swe Win said in order to make more money, he works overtime as often as he can.

“Sometimes we have to work all night. We get double the salary, but we are so tired,” he said.