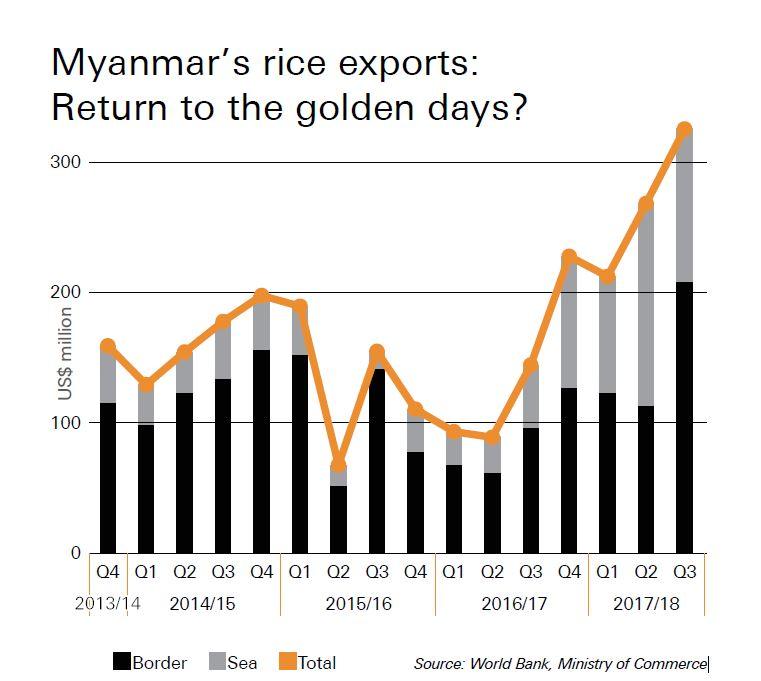

Myanmar shipped a record 3.2 million tonnes of rice in 2017-18 amid a steady growth in paddy production that has enabled the country to regain its position as one of the world’s top exporters.

By HTUN KHAING | FRONTIER

MYANMAR RICE exports achieved a milestone in the 2017-18 financial year, earning more than US$1 billion (K1.3 trillion) from the record sale of 3.2 million tonnes shipped from the country once known as the “rice bowl of Asia”.

However, it will be a challenge for Myanmar to regain its title as the world’s largest exporter of rice, the nation’s most important crop, grown on more than 8 million hectares, (19.7 million acres) or half the arable land.

India, the world’s largest exporter, shipped about 12.5 million tonnes in 2017, followed by Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, Myanmar and the United States, showed the Statista website.

The boom in rice exports, which increased 23 percent in 2017-18, follows a five-decade slump caused by misguided policies and underinvestment. In 1963, the year after General Ne Win seized power in a coup and nationalised most businesses, Myanmar’s exports stood at 1.7 million tonnes.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But in December 1963, Ne Win’s socialist government banned all private sector activity in the rice sector under a policy that prioritised self-sufficiency in the staple. By 1973, exports had plunged to a low of 145,810 tonnes, according to figures on the ricepedia.org website.

The military government that took power in September 1988 retained strict controls on exports but introduced changes in the industry, including requiring farmers to sell at least 12 baskets of paddy an acre (0.4 hectares) to the government at a fixed price.

In April 2003, the military government abolished compulsory paddy sales and permitted farmers to buy and sell freely, but it was not until the 2007-08 fiscal year that restrictions were lifted on exports by the private sector. Since then exports have gradually risen to last financial year’s peak.

The government has set an export target of 4 million tonnes by 2020-21, which at current prices would earn about $1.5 billion in revenue. It also wants Myanmar to become the world’s third biggest exporter by 2020-21, but that’s an ambitious target because of production challenges, including poor seed quality and low mechanisation.

typeof=

In its latest Myanmar Economic Monitor, released on May 17, the World Bank said that rice output grew by 3.1 percent in 2017 because rising demand and higher prices prompted some to switch crops. However, it said that prospects for continued increases in agricultural growth would be limited by constraints to productivity. While the sector employs around half of the workforce, it contributes just 26 percent to GDP.

“Mechanisation rates are improving but remain very low in relation to peers. Myanmar’s agricultural productivity is constrained by an insufficient supply of quality seeds and lack of knowledge of soil nutrients, compounded by a lack of proper storage and transport facilities and processing techniques,” it said.

State-run newspapers have reported that the cost of a bag of urea fertiliser in Myanmar is 17 percent more expensive than in Vietnam, 12 percent more expensive than Thailand and 8 percent more expensive than Cambodia. Fertiliser quality is also a problem in Myanmar.

When Myanmar was under colonial rule, the fertile fields of the Ayeyarwady Delta helped to make the country the largest rice exporter in the world.

U Sein Win, an independent Pyithu Hluttaw MP for Maubin, in the heart of the delta, said that life can be extremely difficult for rice farmers in Myanmar.

He said paddy prices often slump at harvest time, hurting farmers’ incomes. Some of the major challenges to overcome include low quality seeds and fertiliser, as well as a lack of modern agricultural systems.

In 2016-17, total production of paddy was 1327.23 million baskets (each basket weighs 20.9 kilograms), government figures published in state media show. This was harvested from 15.24 million acres (6.1 million hectares) cultivated during the rainy season and 2.46 million acres (995,526ha) of summer crop, according to the figures.

During colonial rule, Myanmar was the world’s top rice exporter, but now ranks fifth behind neighbours including India and Thailand. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

In early March, the Myanmar Rice Federation introduced a basic floor price for paddy. The price, which does not include high-grade varieties, was set at K500,000 per 100 baskets. All MRF member rice mills, traders, as well as agents and private companies will purchase paddy from farmers at the set rate, but pay the market price if it rises above K500,000.

Sein Win questioned the move, saying that farmers were more likely to trust a minimum price set by the government rather than the private sector. He questioned what would happen if the market price fell below K500,000 per 100 baskets.

“Would [the MRF] borrow from the government to cover the loss? The money of the government and traders should not be mixed,” he said.

The floor price policy was announced by State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi at the MRF Stakeholder Forum 2018 in Nay Pyi Taw on March 6, but since then there has been little detail about the policy.

U Ye Min Aung, secretary general of MRF, said the federation will announce more detailed regulations about the new rules in the near future.

He said that 90 percent of rice traders and mill owners in Myanmar are federation members, so he was confident the policy would be adhered to.

“If they don’t follow the designation, what should we do? We are drafting the plans relating to this,” he said.

Many farmers did not know about the fixing of the minimum price, said U Sithu, who farms 50 acres of paddy at Phayataung village in Ayeyarwady’s Ngapudaw Township.

Paddy farmers have received increased support under the National League for Democracy government. When the party took office, farmers could borrow K100,000 per acre from government banks, but soon after that number was raised to K150,000 per acre.

Ye Min Aung said that the floor price was an indication of the government’s appreciation for the country’s farmers, by guaranteeing them a certain income.

Asked why successive governments focused on rice policy, he said, “Rice is politics.”