Most analysis of the November 3 by-elections has naturally focused on the results, and what they can tell us – if anything – about voting trends in the 2020 general election.

Given the low turnout, we should be cautious about drawing conclusions.

Less attention has focused on the process of overseeing the elections. Electoral reform has simply not been on the agenda since the 2015 general election. Any sense of urgency about tackling the serious deficiencies within Myanmar’s electoral system has disappeared.

This is not because those problems were resolved or addressed in any way.

The National League for Democracy’s strong performance meant the result – and, importantly, control of the civilian portion of the government – was never in doubt. Overall, the 2015 poll went so smoothly that the Union Election Commission has rested on its laurels ever since.

Since the NLD took office, the only electoral reform of any note has been the proposed consolidation of the separate laws for elections in the Amyotha, Pyithu and state and region hluttaws into a single text. The laws were already almost identical, so this will hardly count as an achievement when it does eventually receive approval from lawmakers.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

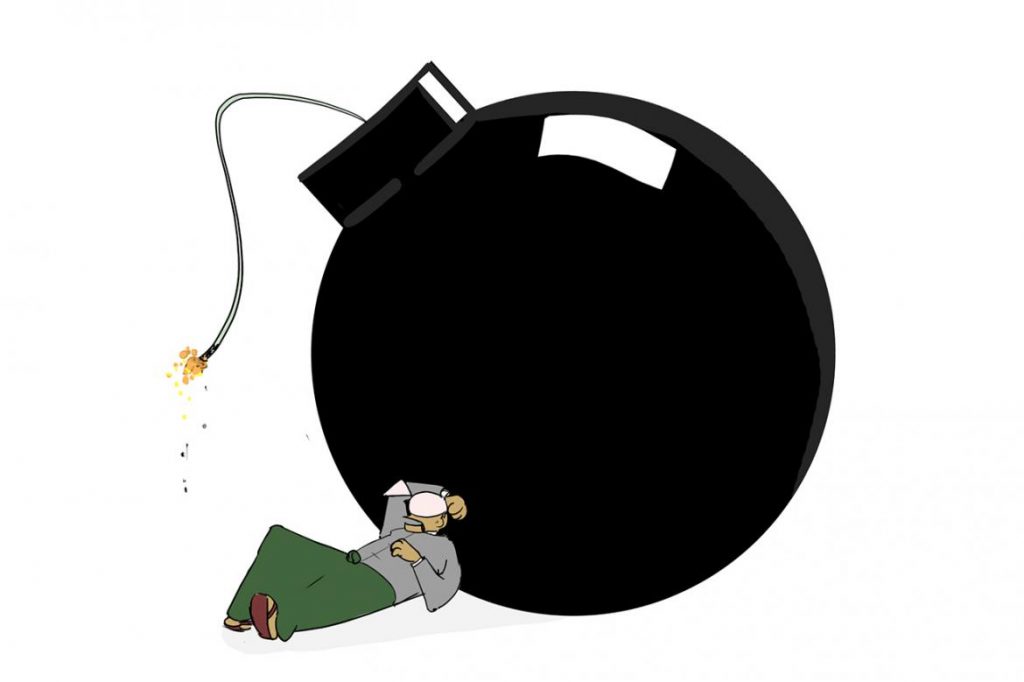

This is short sighted and, one could argue, dangerous. With little at stake in the by-elections, they should not be considered a serious test of the electoral system. It is not unreasonable to expect that the 2020 general election will be just as hard-fought as 2015 and that the result will be closer. The UEC may even have to make a decision that affects the balance of power in a state or region hluttaw, or even the ability of a party or political bloc to choose the president and thus control the government.

So, what are the likely stress points in the electoral system that may come to the fore in 2015?

The vote counting in one constituency on November 3 has already highlighted one of these: advance votes. In the Kachin-2 Amyotha Hluttaw constituency that encompasses Myitkyina, they came close to deciding the outcome.

Out-of-constituency advance voting by military personnel and their families is still a black box: votes are sent by local election sub-commissions to forward bases, where votes are cast beyond the gaze of electoral officials or observers, before being sent back to be counted. In 2010 and 2015 these overwhelmingly went to the Union Solidarity and Development Party (as they did in Kachin-2 on November 3).

In 2015 there were numerous anecdotal reports of irregularities – for example, military personnel admitting that their senior officers voted on their behalf – that for reasons of political expediency went largely un-investigated. In future tight races in constituencies with large army cantonment populations, these votes could flip results.

The low turnout masked issues related to the electoral roll. Although the UEC has updated it since 2015, scepticism among parties over the voter list is still very high. The list should be audited independently, as happens in many other countries, both to make it more accurate and to build general confidence in its integrity.

Campaign finance regulations are still minimal, and allow a considerable loophole in the distinction between “party” and “candidate” spending. As elections become more competitive, we can expect bigger budget campaigns.

The restrictions on the government and its members from taking part in campaigning remain unclear. Many observers noted that during the campaign period for the by-elections, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi visited two of the constituencies in play, Kachin-2 and Kanpetlet in Chin State.

Another problem observed by Frontier is that the UEC in Nay Pyi Taw still does not have a functioning communication system. Several fairly basic requests for information received no official response, despite repeated follow-up attempts.

This underlines that the UEC is a fundamentally unaccountable institution. Post-election disputes are heard by a tribunal made up of UEC members, and their decisions are final and cannot be appealed to an independent court. The commissioners are also appointed at the change of each government by the new president. This undermines confidence in the UEC as an institution and leaves it open to politicisation.

Addressing this last issue may require constitutional change. But many of the other issues around the electoral system can – and should – be taken up now, well before campaigning for the 2020 general election gets underway.