Reports about a busy month in the courts for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and confusion over symbols used on party flags ruffle feathers at censorship headquarters.

The Lady was always big news in the outside world but any mention of her name or activities in the commercial media in Myanmar before August 2012 raised big red flags at censorship headquarters on Wingaba Road in Bahan Township.

Rejected for publication in the October 11, 2010 edition of the Myanmar Times was an Agence France-Presse report about a Supreme Court hearing involving Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The hearing was to consider a “special appeal” she lodged the previous May to challenge her house arrest, which was due to expire a few days after the election.

Appeals against her house arrest had already been twice rejected, the report said. It was a busy month in the courts for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The report mentioned that on October 5, 2010, she had filed a Supreme Court appeal against the government over the decision to deregister the NLD ahead of an election the party decided not to contest.

The only other report rejected from that edition was one of the many censorship decisions that gave rise to bewilderment. After nearly 10 years of censorship rulings at the Myanmar Times, first under Military Intelligence until it was purged in 2004 and then on orders from the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division, I could make an educated guess about a likely reason for its rejection.

It was a report about comments to a group of Myanmar journalists in New Delhi by the joint secretary of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs. Vishnu Prakash had spoken at the inauguration of a training course for 25 Myanmar journalists at the Indian Institute of Mass Communication in New Delhi. Cooperation on security issues was India’s major priority in its relations with neighbouring countries, including Myanmar, he said. My guess for the likely reason of the rejection was that it had nothing to do with the comment about security cooperation. It was because it publicised New Delhi’s praiseworthy move to help build capacity among Myanmar journalists.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

There were people in Nay Pyi Taw who would be thinking that might give the journalists ideas about media reform or the urgent need in Myanmar for similar professional training, which has only become a reality since 2011. It was curious that the 25 journalists included four from state-run media but their participation may have been at the behest of the many progressives in the bureaucracy. There were many of them.

The red pen was wielded more gently in a report about campaigning by the pro-junta 88 Generation Student Youths (Union of Myanmar), which many suspected was so named in a ploy to win votes from supporters of the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society group. The cuts were about confusion among voters over the 88 Generation Student Youth’s use on its flag of a fighting peacock, a symbol used by the NLD.

A man asked about flag-brandishing members of the 88 Generation Student Youths as they passed his tyre shop in Sanchaung Township, replied: “It’s the NLD, right?” Also cut was his response to a question about the parties contesting the election. “I only know the NLD,” he said, an indication he might not have known it was boycotting the election.

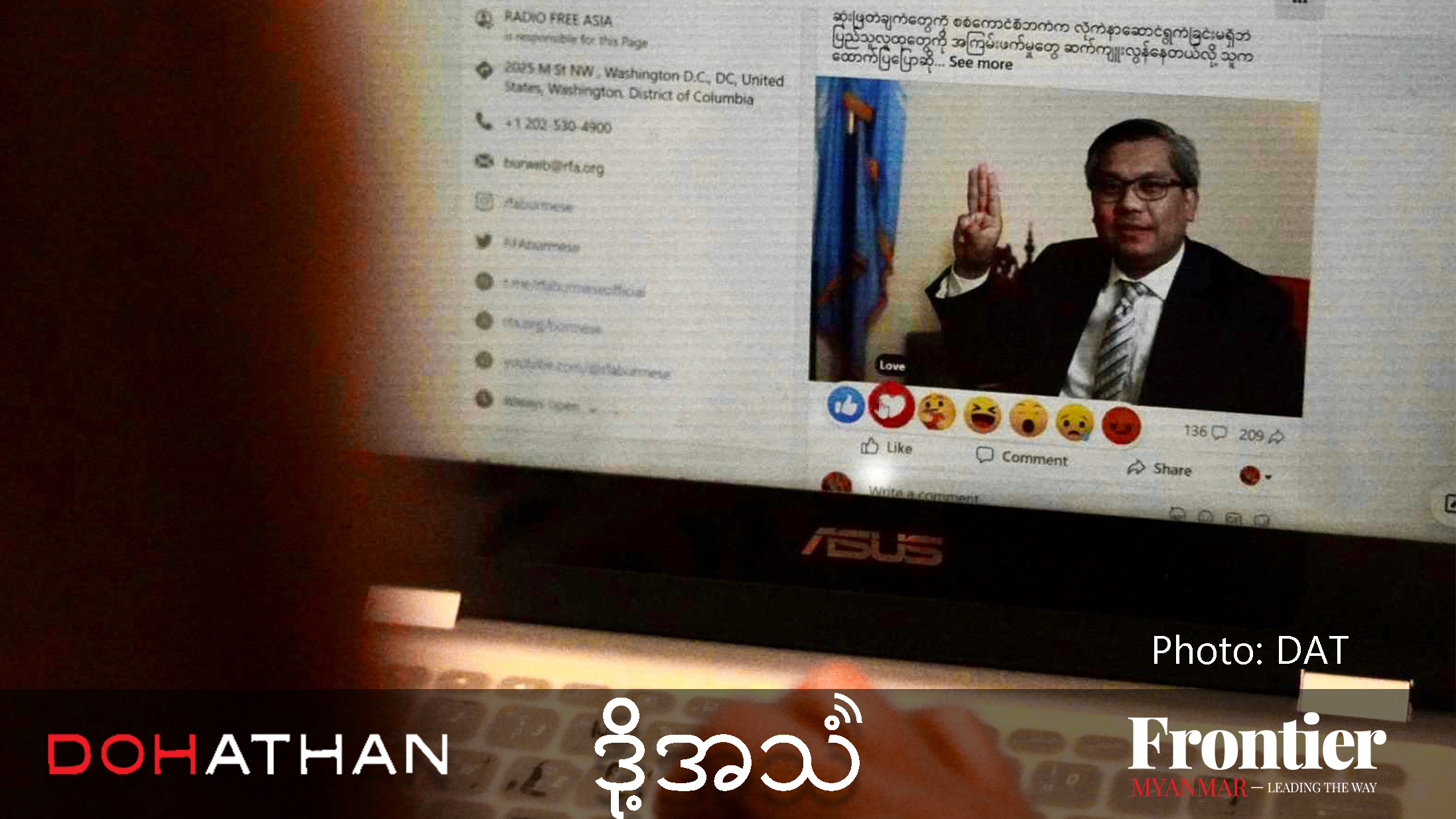

Perhaps he had not been taking evening strolls with a short-wave radio held close to his ear, listening to the Burmese services crackling through the ether of the BBC World Service or Radio Free Asia, a fairly common sight in those days. It was news listeners knew they could trust and trust was an issue explored in a feature report that had the censors’ reaching for the red pen after the first sentence.

The report was about the challenge that reporters in the private-sector print media faced building trust with news sources and their reluctance to speak on the record, even though many were happy to provide information.

Then came a sentence which red-lined to the max, because in explaining a reason for a reluctance to speak on the record it also revealed information about the censorship process. It was about requests by the censors for publications to provide “letters of recommendation” signed by news sources attesting to the accuracy of information they had provided before it could be published. No letter? End of story.