As life becomes ever more digital and fast-paced, some Yangon youth are discovering the slow, unpredictable and life-affirming qualities of analogue film photography.

By TANVI RIISE | FRONTIER

FOR MY birthday last year my mother gave me her old Olympus compact, the same camera that she had used to capture my childhood on film in the 1990s. I was thrilled about the prospect of bringing the aesthetic and feel of those captured memories to moments in my life. At the time I did not have any idea how difficult it would be to buy film rolls in Yangon, where the use of digital technology has belatedly exploded over the past decade. Unexpectedly, in my quest to find analogue materials, I found a young generation of Myanmar photography enthusiasts eager to declare the revival of film photography.

Family tradition

Film photography has a long history in Myanmar, although little of it had been systematically archived until Austrian artist Mr Lukas Birk began digging through Yangon’s antique shops and old photo studios, establishing Myanmar Photo Archive in 2013. Although the first and most renowned photographs were shot by foreign professionals seeking to construct a distinct exotic expression of Burma tailored for the European market, Birk found that Burmese photographers had began to bring their own cultural perspective and lived experience to photography by 1910.

Photography by Burmese remained a restricted phenomenon, however, until materials became cheaper and more accessible to middle class families in the years after World War II. As the market for amateur photography gradually expanded in the 1950s and 60s, families began to document their lives in a new way, capturing informal get-togethers and occasions beyond the rigid format of studio portraiture.

The deepening isolation of the country and the military government’s nationalisation of the photography industry in the 1970s later made amateur photography an exclusive pursuit, with materials for photography in short supply. In an interview with Myanmar Times in February 2018, Birk noted that the photos he found from this period, including portraits of students wearing Western style disco clothes, nevertheless challenge the narrative of a country in decline. Through photography, a sense of joy persisted.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

U Aye Myint, 59, belongs to one of the families in Yangon that had a camera in the 1970s. He clearly remembers his first camera, a so-called “spy cam”, which he obtained in 1974 at the age of 14. His father, already a photography enthusiast, taught him how to use it. His next camera, a Nikon FM2, would become his all-time favourite, cementing his love for photography. He has kept all the photos of his friends, family and travel experiences, including holiday memories from Ngapali beach in Rakhine State.

Recently, Aye Myint’s 23-year-old son, Ko Thein Htike Zaw, who prefers to go by the name Frederick Lee, browsed through these photos. “It’s fascinating to learn about what life and culture was like in Myanmar in the 80s from the photos my father took,” Frederick told Frontier at his father’s clinic in downtown Yangon. In line with family tradition, he started taking photos with his father’s old point-and-shoot camera when he was six, and now has his own Nikon FM2.

In 2011, the advent of digital photography put Frederick’s passion for film photography on hold. As the economy was liberalised, digital cameras and smart phones became increasingly common and cost efficient vis-à-vis the precarious process of developing film. The last remaining film lab in Yangon closed four years ago, and it became almost impossible to buy film rolls except by mail order from suppliers in Singapore or Bangkok.

Yet while film seemed increasingly obsolete in Myanmar, young people still remembered, or had parents or grandparents who remembered, the magic of analogue photography. Their photos and cameras are still to be found in shelves and boxes tucked away in homes across the city.

Analogue photography enthusiast Ko Thein Htike Zaw (left), aka Frederick Lee, with this father and fellow enthusiast U Aye Myint (centre) and younger brother, who goes by Alex Lee. (Tanvi Riise | Frontier)

The lab

Some of these cameras are now resurfacing thanks to Film Lake, a film processing lab in Yangon founded four months ago as a side-project by photographer and film maker Ko Htoo Tay Zar, 30. He became interested in film photography as a hobby nine years ago and eventually taught himself the craft of film processing to avoid the hassle of buying and developing film from overseas. He watched videos on YouTube, bought the processing chemicals abroad, exchanged knowledge with foreign film photographers whenever they were in town, and experimented on his own film rolls.

After about six months of practicing different techniques, he felt confident enough to mix the chemicals correctly and develop various types of film with precision. Finally, his friends convinced him to open a film lab in his studio on Aw Bar Street in Tarmwe Township, and to import film rolls from Bangkok for them to buy. After noticing the camera hanging around Htoo Tay Zar’s neck at a wedding of a mutual friend, Frederick joined the community of young film enthusiasts whose interest in analogue photography was gaining momentum.

I found Film Lake and Htoo Tay Zar through a photographer friend of a friend when I needed to develop two 35mm Kodak film rolls. He used the rolls to demonstrate the process in his studio kitchen, carefully heating two glass bottles of chemicals to the required temperature before pouring them in a light proof container and tossing it a specific number of times between measured intervals. I was struck by how much it resembled an advanced culinary preparation. After a day of air drying, my strips of processed film were ready to be scanned and enjoyed.

“Besides the fact that I use a digital scanner once the film is processed, the process is very similar to how the photo studios in Yangon used to do it. They never got to the commercial scale it did in the West,” Htoo Tay Zar said.

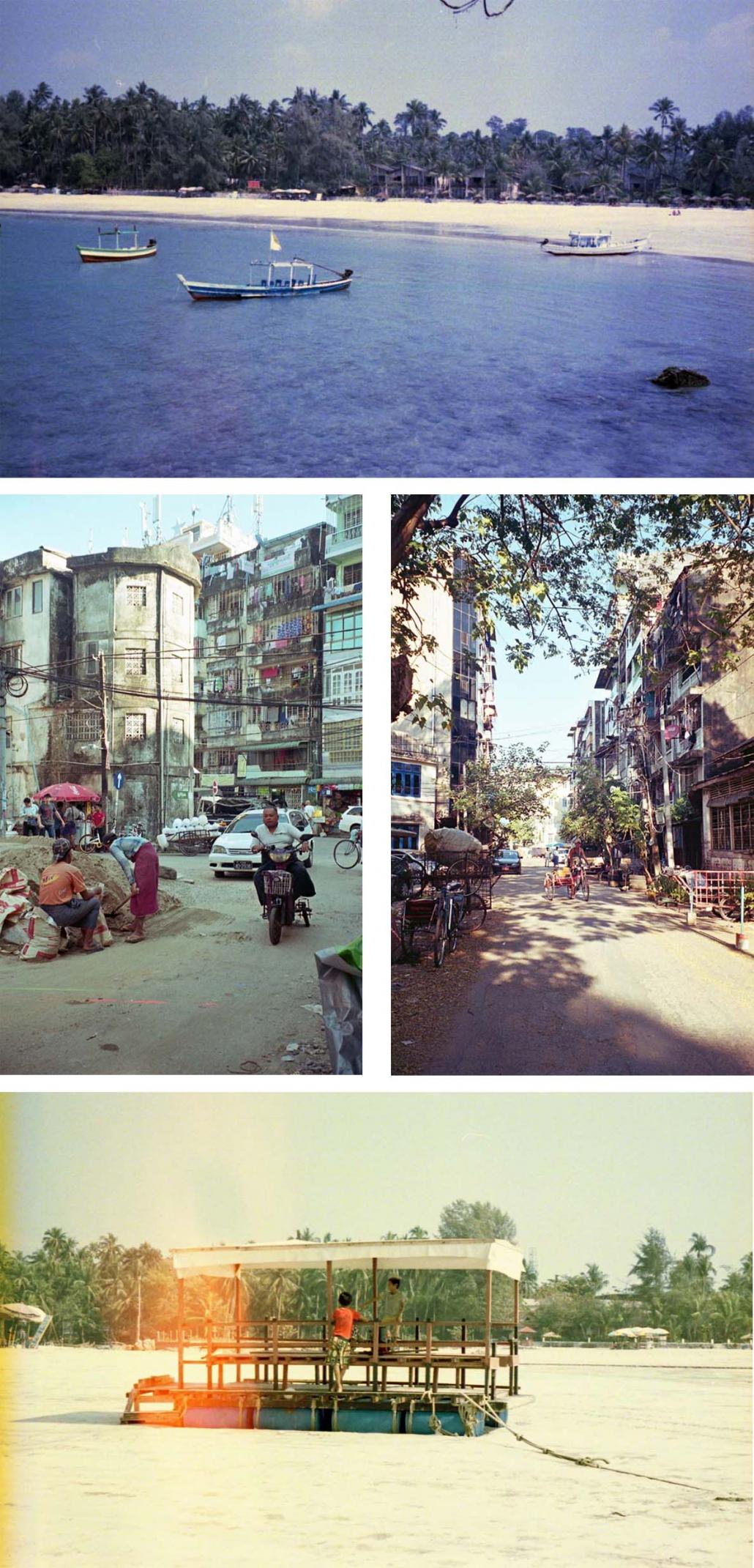

Analogue photographs taken in Myanmar by Tanvi Riise

Blurs and scratches

Htoo Tay Zar’s hobby project has grown rapidly since he began to serve the analogue needs of his 10 or so photographer friends. “Each month more and more people have been joining. There are around 40 people in Yangon shooting on film now, each of them using 1-2 film rolls per month,” he said. Most had never used an analogue camera until they found one owned by their parents or grandparents and took it to Htoo Tay Zar to ask if it was still usable.

“I have to answer at least two or three people every day, asking me how to operate their camera, how to choose the right film, and how to develop. I think they like the feeling of holding the camera that their parents used to use,” he said.

The aesthetic quality of film photography is being embraced by young people as a more original and authentic alternative to the popular trend of adding digital filters of grains, scratches and vintage colour schemes to photos taken with digital cameras or smartphones.

For Frederick, the unpredictable imperfections of analogue photographs – blurs, light leaks and scratches – are what elevate a photo to something greater than what meets the eye. “People always say detail and sharpness are important for good photos,” he said. “But since you can see everything in nature with the sharpness of your vision, and now also through digital cameras, I think it can get boring. I want photography to bring something different from what we can see with our eye. Sometimes inaccuracy makes a photo valuable and moving.”

Ko Htoo Tay Zar inspects film rolls at his studio in Yangon. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Stealing the moment

Above the benefits of inter-generational exchange and aesthetic resonance, however, is the heightened focus that analogue photography demands of the photographer. It’s a mixed blessing that might seem purely inconvenient: you are limited to only 36 frames a roll; it takes a week before you see the result, making it harder to continuously evaluate your work; and it’s not connected to the internet.

Yet both Htoo Tay Zar and Frederick say these apparent limitations are exactly what pushes photographers to improve their skills. The more precious the frames are, the more conscious the photographer is in selecting which moments to capture, actively choosing how to frame a situation rather than filling up megabytes with near identical versions of the same, gradually stiffening scene. “If you miss the moment, you won’t take the photo after all,” said Htoo Tay Zar.

For Frederick, the restrictions of film ultimately breed confidence. “When you take a photo with a film camera, you’re sure that you’ve shot a good one. I can’t explain why, you just know. It’s about the authenticity and instinct in the moment,” he said. “With digital photography you may feel less certain, struggling to select a good one out of the hundred photos you took of the same thing.”

Moreover, the excess capacity in digital photography may cause people to lose out on the moment they’re trying to capture in the first place. “I think the digital transformation is making people lose the moment,” said Htoo Tay Zar.

“You may see a beautiful sunset with your family but you’ll be busy taking 50 photos of it, forgetting the people around you as you’re looking at the screen trying to select the best one out of the 50,” he said. “The limit of 36 frames gives you more time to be present so you can enjoy the moment with the people you love. It’s like a detox.”

With billboards advertising the latest camera-equipped smartphone towering over the streets of Yangon, the idea that the moment and content of a photo is more important than the technical specifications of the device that took it can be liberating to a generation increasingly pacified by the speed and excess that are inherent in digital technology. As more people rediscover the value of the slow and unpredictable, film photography can offer a more human mirror to Myanmar history, as it continues to be lived as a series of deeply felt personal moments.