A myriad of challenges has created a dearth of on-the-ground conflict reporting in a nation at constant war for decades, but the law itself may be the biggest obstacle.

By PYAE SONE AUNG | FRONTIER

Although a temporary ceasefire has momentarily halted the war raging for the last several years in Rakhine State, a flare up between two ethnic armed groups in northern Shan State displaced thousands over the Christmas and New Year’s holiday. This state of endless war is nothing new for Myanmar, which has suffered numerous civil wars nearly since the moment of its independence. But a dearth of on-the-ground war reporting is keeping the grim realities of these conflicts obscured from the population, stifling debate on their true cost to the country.

The challenges for reporters are myriad, from COVID-19 travel restrictions, deep suspicion of journalists from armed groups including the military, and the nature of war itself. But perhaps the most frustrating is a legal code and pliant judiciary designed to cower reporters into silence.

Frontier spoke recently to several veteran Myanmar war reporters about their experience covering conflict. The challenges are staggering, but for each, quitting is not an option.

Mistrust

Ko Kaung Htet tried to concentrate on his camera’s viewfinder, which was focussed on the inside of a tent at a camp for displaced people, when he felt a slap on the back of his neck. The photographer staggered a few steps forward, then turned to find a dagger-wielding soldier of an ethnic armed group – he preferred not to disclose which – standing behind him, shouting in a local dialect he couldn’t understand. Each incomprehensible syllable carried forth the stench of cigarette smoke and alcohol.

Kaung Htet immediately realised there’d been a miscommunication. He began explaining to the soldier in Burmese that he was a news photographer and had permission from the group’s commander-in-chief to be shooting there. He said he meant the soldier no harm and tried to pantomime an apology, offering up the press pass hanging around his neck.

A wounded Kachin fighter is helped back to safety during heavy fighting near Laiza in early 2013. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

For a moment, the soldier disappeared into an army tent. Kaung Htet thought about running, but before he could, the soldier reappeared, his dagger replaced with a rifle aimed right at Kaung Htet. He got onto a motorbike and ordered Kaung Htet to start walking toward another tent, following him on the bike with the rifle trained on his back. Kaung Htet heard the rifle cock, sending shivers up and down his spine as if a thousand ants were crawling up his back.

“I summoned my wits and started to think of a survival strategy,” he told Frontier of the 2012 incident. “I feared I would be tortured or killed in the next tent.”

Within a few steps they reached a ditch about three feet wide with a rickety bamboo bridge slung across it. He could jump across, he figured, but the motorbike likely could not. Just then, a local elder emerged from a nearby tent and began speaking in the local dialect to the soldier. The soldier cut the engine on his bike and set the rifle down. Kaung Htet seized the moment, leaping over the ditch and sprinting behind a cluster of tents.

He learned that day that communication flows are unreliable in combat zones. The most senior-levels of the ethnic armed group had okayed his reporting on the frontlines and in the camps for internally displaced people, but the clearance had clearly not filtered down to the soldiers on the ground, who too often look on journalists with suspicion. Even if granted official permission, a war reporter’s fate can be left to the whims of a single soldier’s judgements and inclinations.

“Journalists get shot, they get injured or die on the frontlines, because armed groups believe they are spies or enemies,” Kaung Htet said.

That suspicion runs even more deeply through the Tatmadaw. One well-known example is that of Ko Par Gyi, who was taken into custody by a Tatmadaw battalion on September 30, 2014, while covering fighting between the military and the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army. On October 4 he was shot dead. The military claimed Par Gyi was working as a “communications officer” for the DKBA, but relatives, journalists, international rights group and the DKBA itself dispute this claim. His family was never notified of the burial, and the military only acknowledged his death on October 23. When his body was later exhumed, it was riven with signs of torture.

Like so much else in the country, ethnicity compounds these trust issues. Many ethnic armed groups harbour deep suspicions of journalists generally, and Bamar journalists particularly. The chief enemy and greatest threat to many of these groups is the Tatmadaw, a deeply Bamar institution. The first assumption for the soldiers and commanders of ethnic armed groups is that any Bamar person posing as a reporter is actually a military spy. (Kaung Htet is both Bamar and Mon.)

This is not just limited to Bamar reporters. If a journalist is clearly Myanmar but not obviously of the same ethnicity as the ethnic armed group in question – if a commander cannot immediately tell whose ‘side’ they’re one – the reporter will likely be denied access. The armed groups are more trusting of foreigners, who they assume have no Tatmadaw connections and no dog in the fight.

“I’ve taken Myanmar journalists to visit some of the ethnic armed groups, and they’ve straightaway said, ‘you can come, but these guys need to be sent back’,” said Frontier photo editor Mr Steve Tickner, an Australian who has been covering Myanmar’s war zones for nearly a decade.

Indiscriminate killers

Of course, if reporters do make it past these significant hurdles, they face the same threats that any other reporter faces in a war zone. But, while some militaries at least try to avoid targeting journalists and aid workers, many in Myanmar do not.

In 2015, when MRTV-4 reporter Ko Myat Thiha Maung was covering the conflict between the Tatmadaw and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, in 2015, his news van was stopped behind a Red Cross vehicle. It didn’t take long for him to realise the vehicle had been attacked; a Red Cross volunteer was lying on the road bleeding. His colleagues had abandoned the vehicle and were hiding in a nearby ditch. Bullets flew in the distance.

When he and his crew began taking photos, the bullets turned toward their news van. One made it through the siding and struck Myat Thiha Maung in the arm. The news crew made their way to the ditch as well, where they huddled for six hours, until Tatmadaw troops came to their aid. Myat Thiha Maung was later hospitalised for two months and operated on four times.

“To this day, a few fingers on that arm have still not regained their original flexibility,” he told Frontier.

There are more than just bullets to watch out for. Myanmar is one of just 32 nations that have not signed on to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty (see page 18), and the many landmines scattered across its frontier areas are yet another indiscriminate killer that reporters must contend with. Ko Lawi Weng, a veteran freelancer and regular Frontier contributor, recalled the aura of suffering and death he felt while covering the Ta’ang National Liberation Army’s conflict with the Tatmadaw in June 2017, when every step brought the possibility of death. Between 1999 and 2019, landmines have killed or maimed some 5,000 civilians. “My knees were shaking the whole time,” Lawi Weng said. “The whole scene chilled me to the bone. I wanted good photos but dared not approach too close.”

Even with a major media house backing them, Myanmar journalists’ jobs rarely come with medical or life insurance.

The law

But sadly, the greatest threat journalists face is the law itself. The Tatmadaw and the government have a plethora of legal tools with which to punish journalists simply for reporting.

In the current conflict in northern Rakhine, the government, at the Tatmadaw’s urging, has branded their rival Arakan Army as a terrorist organisation – a designation that has allowed it to charge any journalist that seeks a comment from the AA under the 2013 Anti-Terrorism Law, which bars associating with designated terrorist groups. This likely goes a long way in explaining the paucity of first-hand reporting on that conflict since last April, when the government gave the ethnic armed group the terrorist designation.

Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law, which deals with defamation and has perhaps garnered the most attention from international rights groups, “has been used repeatedly to restrict freedom of speech and expression” for “reporters, politicians, and social media users”, largely by the military, according to the rights group Burma Campaign UK. According to the free expression group Athan, between 2016 and March 2020, 34 journalists had been charged under this law, and another nine under similar laws in the Penal Code.

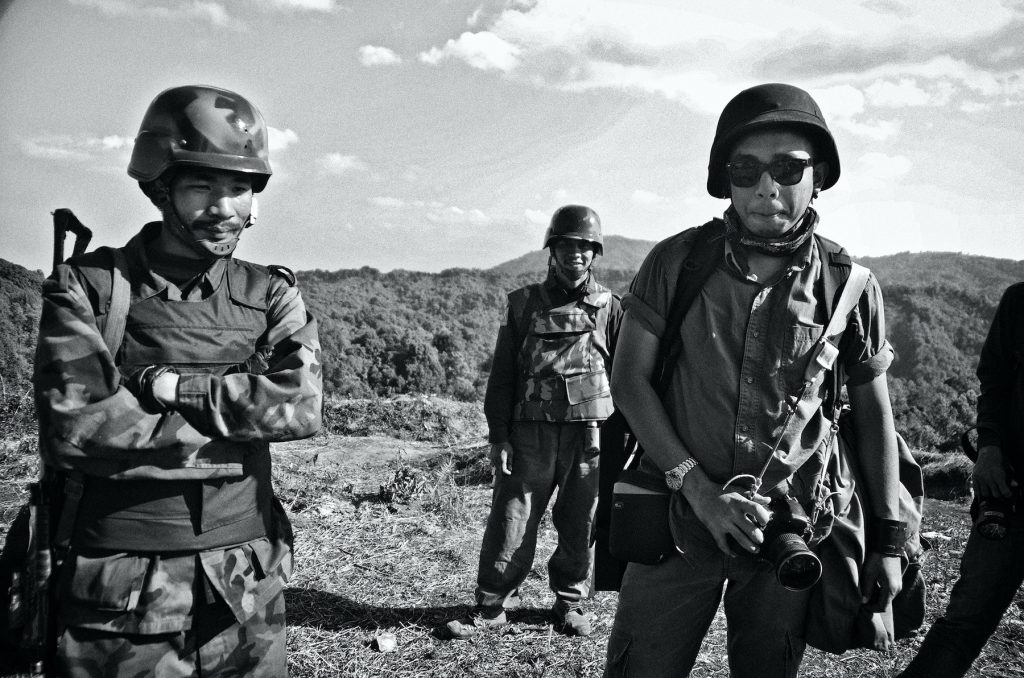

Photographer Steve Tickner reporting on conflict in northern Shan State in February 2016. (Lawi Weng)

Like the Anti-Terrorism Law, the Unlawful Associations Act makes it illegal to meet with or “assist” any “unlawful association”, and carries a two-year prison sentence. The editor-in-chief of the Rakhine-based Development Media Group, Ko Aung Marm Oo, has been in hiding for nearly two years after being charged under that law for reporting the outlet published on the conflict there. In 2015, Lawi Weng and two other journalists were arrested at a military checkpoint while returning from covering the conflict between the Tatmadaw and the TNLA and charged by the military under the law. They were jailed for three months, but the military ultimately dropped the charges.

Between 2016 and 2020, under these and other laws, the government has brought charges against 34 reporters, the military against 11 and ethnic armed groups against two, according to Athan. With a judiciary still heavily under the sway of the military, convictions are often forgone conclusions as soon as charges are brought – unless the military or government decides otherwise, as in Lawi’s case.

“It doesn’t matter if you can prove what you said was true. If the military takes it as an insult, the court will deliver a prison sentence,” said Tickner.

Bearing witness

Tickner keeps a photo he took in Kachin State in January 2013 on the wall of his Yangon apartment. In it, a bloodied civilian lies lifelessly in the middle of Laiza town. One night, while he and others sat around a fire, the Tatmadaw shelled the town centre at random, killing him and another civilian.

“That was a war crime, and the Tatmadaw commits them on an almost daily basis,” said Tickner. He believes suchphotographs most viscerally show the truth of Myanmar’s conflicts, and are the most powerful evidence of the atrocities of war. They are a way for the whole nation to bear witness.

Filling the vacuum of war reporting and photography that now exists in Myanmar is the propaganda, disinformation and hate speech promulgated by interested parties to any conflict. This is no accident. By depriving people of the tools needed for a robust, critical, and public deliberation on the means and motives of the Myanmar military’s battles, true democracy over matters of war and peace will remain out of reach in Myanmar.

This is helping push the country dangerously down the path of ethnonationalism. The majority Bamar, under decades of state and military propaganda, have grown to believe that ethnic minorities are the enemies of national unity. This will only help swell the ranks of ethnic armed groups, whose people have more than enough grievances – inequality, ethnic and religious discrimination, outright oppression – to rally around. But only truth can lead to unity, peace, and progress. To that end, an open and free media is essential.