A Frontier investigation has uncovered a network of Facebook accounts sharing disinformation attributed to “Radio Free Myanmar”, with a spike of activity targeting the ruling party and Rohingya Muslims during the lead-up to November’s election.

By BANYAR KYAW, PHONE HTET NAUNG, ALEX BEATSON and ANDREW NACHEMSON | FRONTIER

It looks like Radio Free Asia, sounds like Radio Free Asia and even purports to be from the same country as Radio Free Asia. But anything beyond a cursory glance reveals that Radio Free Myanmar is nothing like the United States-based media outlet that was such an important ally of Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement.

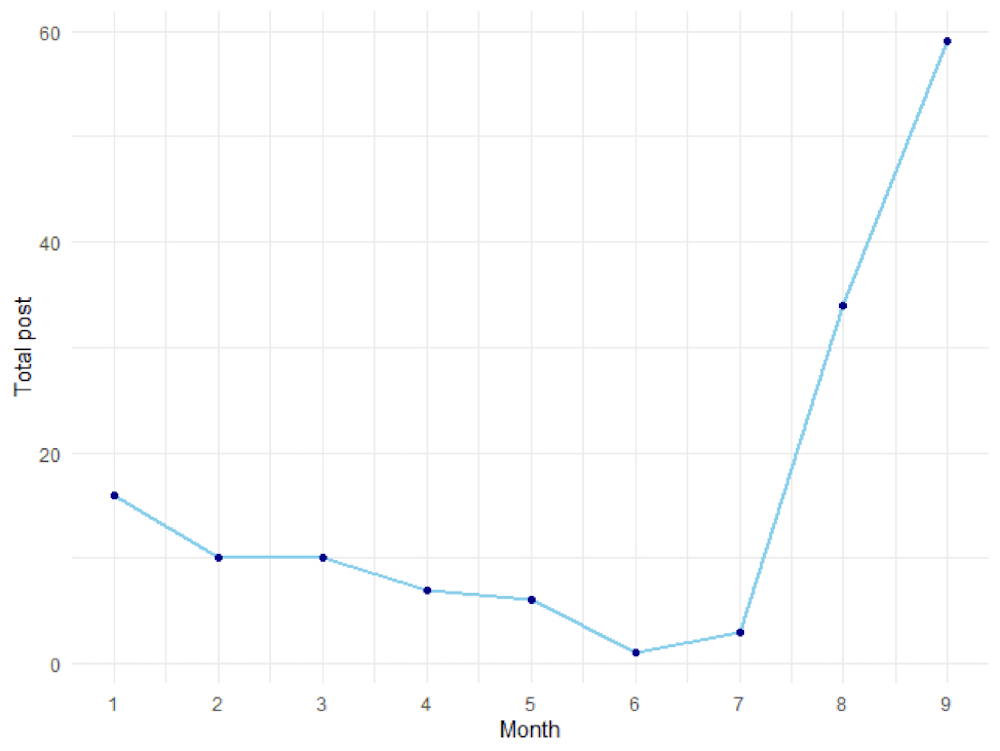

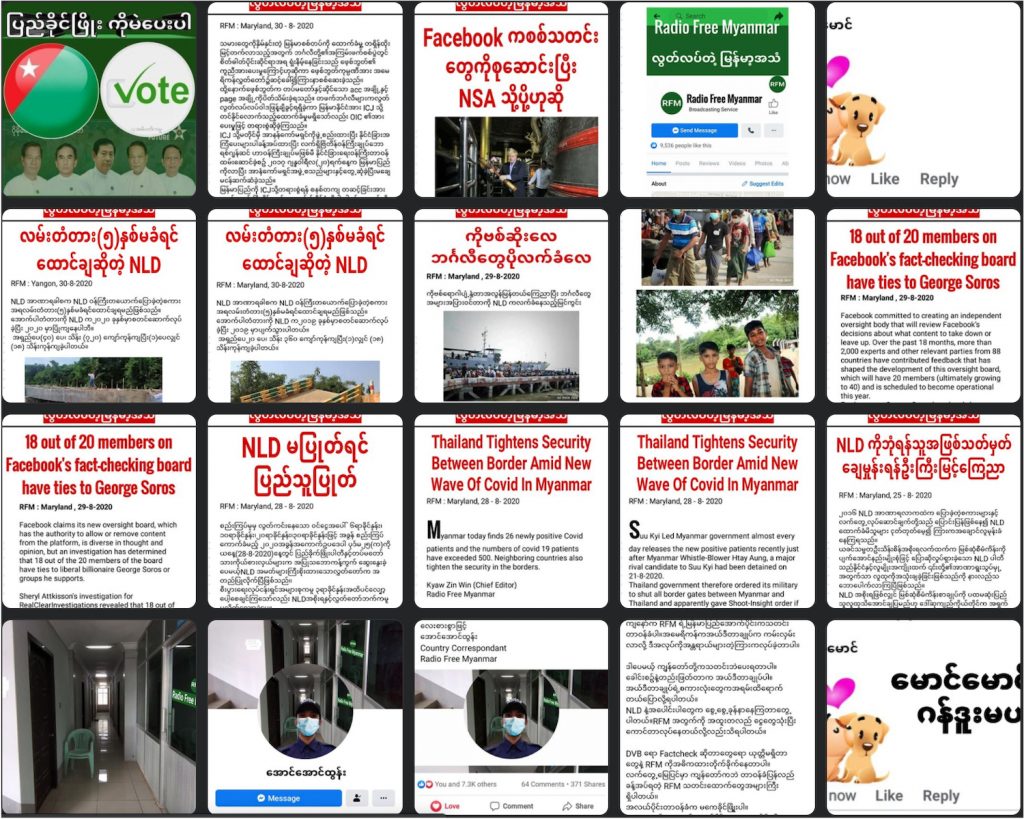

Rather than a reputable news organisation, RFM is spreading disinformation – usually about the ruling National League for Democracy and Rohingya Muslims – that is almost certainly aimed at influencing Myanmar’s November 8 election. Although RFM emerged in late 2019, the amount of RFM content surged in August and September as the election drew closer. The vast majority of RFM content is disinformation.

Frontier’s investigation into RFM over the past two months has uncovered a network of linked Facebook accounts and pages that are being used to spread RFM misinformation through the social media platform. The users have been reported to Facebook, which is conducting its own investigation as a result of Frontier’s work and has locked their accounts until they verify their identity.

To combat disinformation related to the November 8 election, Facebook has introduced a range of measures, including AI to proactively detect hate speech before it becomes widely spread, partnerships with third-party fact checkers, and increased political ad transparency. Those behind RFM, who appear to be supporters of the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party, have employed methods that appear to be aimed at avoiding detection and removal from Facebook, where much of its content is shared.

For example, there is no RFM Facebook page; individual pages and users post content purporting to be from RFM. Disinformation posts attributed to RFM usually originate as photograph templates that look like screenshots of news articles (often no such articles exist). These templates seem to be created off Facebook before being shared as original posts on Facebook. Less frequently, disinformation posts originate on a WordPress blog and are then shared to Facebook. By doing this, it makes it harder to simply search a link and find every time it’s been publicly shared, and multiple different accounts are sharing content, rather than it being concentrated in one group.

Inside the RFM network

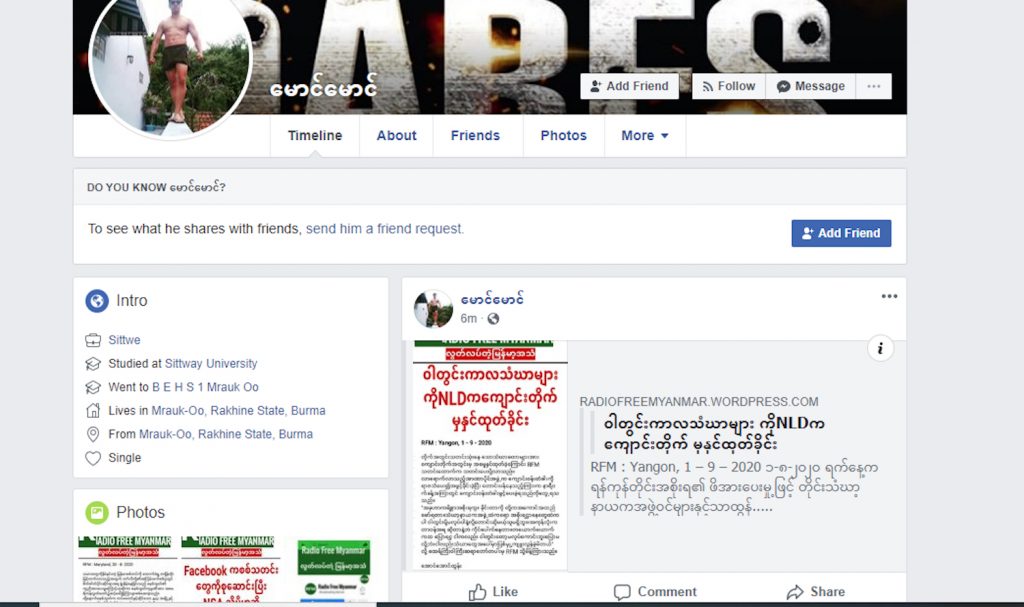

Much of the recent RFM content seems to originate from one profile, Maung Maung, whose profile picture and cover photo both encourage people to vote for the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party. Although the account was only created in August, it has posted over 400 pieces of content attributed to RFM and is often the first place RFM content appears on Facebook.

Maung Maung has been posting progressively more pro-military content. For example, on September 27 and 28, the account posted or shared 20 posts, all either pro-military and USDP or anti-NLD. Of those, nine were RFM content, and eight of these were original posts rather than shares. The account also shared two posts from official, verified USDP accounts during that time.

Maung Maung frequently posts content from RFM that criticises, attacks and insults the NLD, often while spreading false information. On August 26, the account posted an RFM template falsely accusing the NLD of restarting the controversial China-backed Myitsone Dam, which was suspended nearly a decade ago. The post accused State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi of “shamelessly lying” about the dam and called the NLD “our enemy”. In another post, Maung Maung shared an RFM template claiming falsely that under the NLD’s new tax law even a beggar with an income of K1 will be forced to pay 6 percent tax, leaving them with only 94 pya (K1 is equal to 100 pya).

Although those posts were among the most widely shared on Maung Maung’s page, they were only shared 169 and 375 times, respectively. This appears to be deliberate: Maung Maung reminds its followers, “Don’t share my post – just copy and paste.” The account seems to be attempting to limit the amount of attention it gets directly, perhaps to avoid being shut down.

Some users follow this advice, copying and pasting the content, allowing it to spread to an even larger audience without directly implicating Maung Maung. For example, a Facebook user named Thuya Kyaw shared an RFM template on September 3 claiming falsely that the NLD had banned food donations to monks on the full moon day of Waso, which he described as a crackdown on Buddhism. The post, which also claimed falsely that the NLD permitted exceptions to COVID-19 regulations for Muslim religious ceremonies, attracted nearly 4,000 shares and 1,400 likes. The same template, however, was published a day earlier by Maung Maung – visible to his friends only – and received just four shares. The accounts that go on to share Maung Maung’s content are usually friends with the page and sometimes interact in the comment sections of Maung Maung’s posts.

Facebook told Frontier that it is aware of RFM and has “taken action on a number of pieces of content”. “In fact, the first piece of content that we removed under our specific Myanmar elections misinformation policy was content attributed to RFM,” said Mr Rafael Frankel, director of public policy for Facebook in Southeast Asia. According to Facebook, that post falsely claimed that the NLD was replacing its candidates with Rohingya – an attempt to smear the NLD by playing on racial and religious prejudices against the Muslim group. Facebook verified that the post was “misinformation” and removed it as “content that could damage the integrity of the Myanmar election”.

U Myint Kyaw, joint secretary of the Myanmar Press Council, called RFM “propaganda”, “psychological warfare” and “fake news”. He said it is “difficult to say” who is behind the RFM content, but in his view they are clearly “trying to gain an advantage for extreme nationalists and the USDP”. He warned that such content could not only influence “decision making” around the election, but even “lead people to violence”. Despite Myint Kyaw’s clear warning, the MPC has not yet added RFM to its list of websites and social media pages it says are peddling “fake news”.

RFM has also caught the attention of digital rights group Myanmar ICT for Development Organization, better known as MIDO, whose fact-checking initiative “Real or Not” flagged RFM as disinformation. Fact checker Ko Thet Min said RFM posts are “spreading in USDP and Tatmadaw groups” but added that MIDO has not been able to confirm if it is directly linked to the military. “Their aim is to distort the ruling party with fake news during the election,” he said.

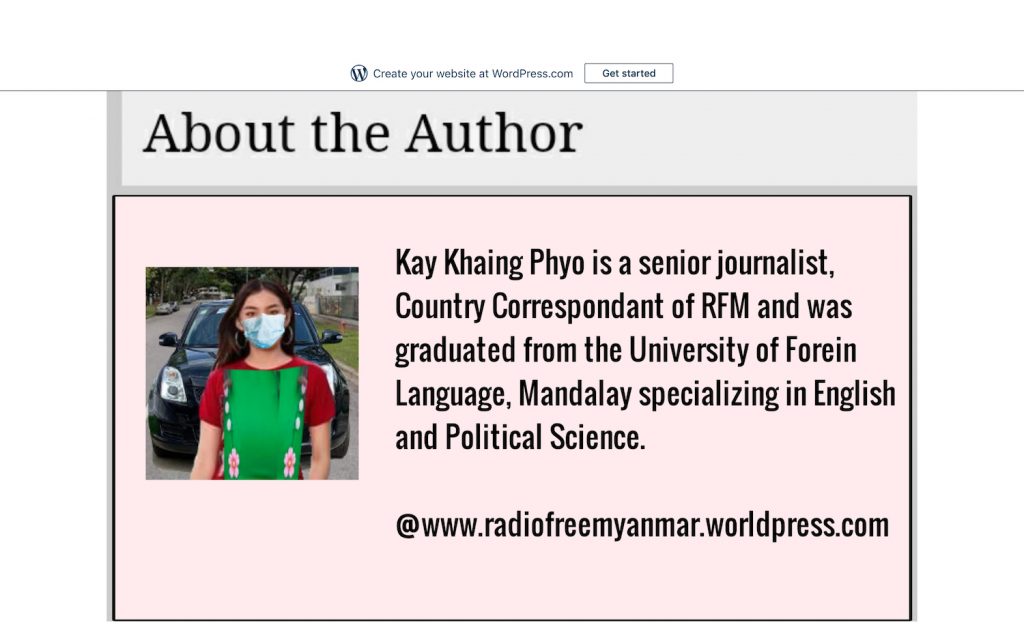

He said the WordPress website appears to have been created in an effort to build RFM’s credibility by making it look like a real news outlet. Content is often bylined and has photographs of the supposed authors, but Thet Min said these profiles were likely fake.

The authors include “executive editor Kyaw Zin Win”, which the page claims to have gone to the University of Maryland. The biography for “country correspondant [sic] Kay Khaing Phyo” claims she studied English and political science at the “University of Forein [sic] Language” in Mandalay.

MIDO traced the photo of “Kyaw Zin Win” back to a Chinese news outlet – the man in the photo is actually a photographer from Nepal. The photo of “Kay Khaing Phyo”, meanwhile, has clearly been taken from somewhere on the internet, but is so heavily photoshopped – a green Myanmar blouse has been crudely pasted over a red t-shirt that is still visible – that it is difficult to trace with reverse image search technology.

Avoiding detection

The earliest example of an RFM post Frontier uncovered was published on November 8, 2019 by an account named Poe Boroz, which used a photo of a Myanmar model as its profile picture. The account posted frequent references to RFM and portrayed it as a US-based media organisation. Poe Boroz shared a job advertisement from RFM that claimed it was based in “Lexiton”, Maryland – a misspelling of Lexington. A few days later, the page shared another RFM post attempting to refute accusations that RFM spreads disinformation. Again, the post claimed that RFM is based in Maryland, but the accompanying map pointed to a location in Mandalay. Poe Boroz has since gone quiet, with no posts of any kind since May.

Frontier found that Poe Boroz and Maung Maung are both admins of a group called Sett Lwin Moe that is a breeding ground for pro-USDP and anti-NLD content, including RFM templates. The other admins of the group, like the similarly named Seh Lwin Moe, also share RFM templates to other pro-USDP pages with larger audiences, like this post which claimed a news presenter cursed people who mocked Aung San Suu Kyi.

Seh Lwin Moe has created posts claiming to be a member of the Tatmadaw stationed in Shan State and his profile picture depicts a man in a Tatmadaw uniform reclining while holding a gun. Another admin, Pyi Sount Thar Kaung, has over 27,000 followers and has shared 300 RFM screenshots and videos since 2019. In January, the page posted an RFM video falsely claiming that Rohingya were studying in Yangon at government expense that received 1,300 reactions and 4,400 shares.

All three of these pages went quiet in May – Poe Boroz and Seh Lwin Moe both made their last posts on May 16 – but Pyi Sount Thar Kaung has shown brief signs of life again recently, making three posts since the end of August.

Frankel said RFM poses a challenge, because it doesn’t have an official page or account on Facebook. “What we can do is somewhat limited,” he said. Facebook has also investigated RFM, but “can’t really tie it to” any specific organisation or group. However, RFM has become something of a red flag for Facebook, with Frankel saying that any time they see the RFM logo, they know the information is “likely false”. Frankel said Facebook can take action against pages and accounts if they are found to be “serial spreaders of misinformation”.

After Frontier shared its findings with Facebook, the admins of Sett Lwin Moe were put into a fake account checkpoint, meaning the users will not have access to their accounts unless they can prove their real identities. During this period, the accounts are not viewable to the public.

When Frontier contacted the Maung Maung account, it denied having any affiliation with RFM, despite frequently sharing content that could not be found elsewhere. The user said they were simply a fan of RFM’s “strong” reporting on issues that other media outlets “are afraid to mention”.

The USDP also denied any relation to RFM. Spokesperson Daw Nan Mya Mya Mie Mie Zaw said: “I do not know RFM … I do not want to comment on an unknown case.”

She acknowledged that USDP supporters may be spreading disinformation, but said supporters of other parties had been doing the same.

Myint Kyaw from the MPC said one of the difficulties in combatting disinformation in Myanmar is that the major political stakeholders only care about the issue when disinformation affects them negatively. Otherwise, they show little interest. “They say nothing,” he said, “when fake news has the same purpose as their policy or ideas.”