The objectives and slogans of anti-junta protests across Myanmar are carefully coordinated and agreed on by a wide array of resistance groups, with the current focus on opposition to the military’s planned elections.

By FRONTIER

Carrying banners bearing revolutionary slogans, around 100 villagers in central Sagaing Region march under the fierce sun in protest against the military regime.

Elderly women with flowers in their braided hair are joined by children, as well as by men holding flags of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions and the General Strike Committee. All chant slogans of the Spring Revolution, some through loud hailers, while fighters of the local People’s Defence Force provide security.

The banners read, “Demolish the fascist army, create a new society”, as well as, “Boycott the fascist election”, and, “Walk boldly along the federal road.”

The demonstration in Ayadaw Township is taking place on March 27 – a date celebrated by the regime as Myanmar Armed Forces Day with a display of its military might in the capital Nay Pyi Taw, but now widely marked by anti-junta forces as Anti-Fascist Revolution Day. This was the original name of the holiday, created to commemorate the fight against Japanese occupation in World War Two.

The scene is repeated across the country, with everything from speeches and slogans to the singing of revolutionary songs coordinated by civilian resistance organisations known as strike committees.

In Myanmar, protests of this kind are called thabeik, a Burmese word that’s generally translated as “strike”, despite these events being closer to demonstrations than workplace walkouts.

“Public strike groups in various places are calling for strikes with the same slogans in other states and regions today,” explained Ma Kaythi*, a member of the Ayadaw Township Public Strike Steering Committee, which was joined by Wetlet and Tabayin township strike groups on March 27.

“The protest themes today are our objectives of getting rid of the fascist army and boycotting the elections they are planning,” she explained.

Increasing coordination

Elsewhere in Sagaing on that day, activists of the General Strike Committee of Nationalities, supported by the Monywa Youth Association, organised a protest rally in Salingyi Township, home of the controversial Letpadaung copper mine. Participants set fire to military uniforms and carried banners with the slogan, “Take the federal way and boycott fascism.”

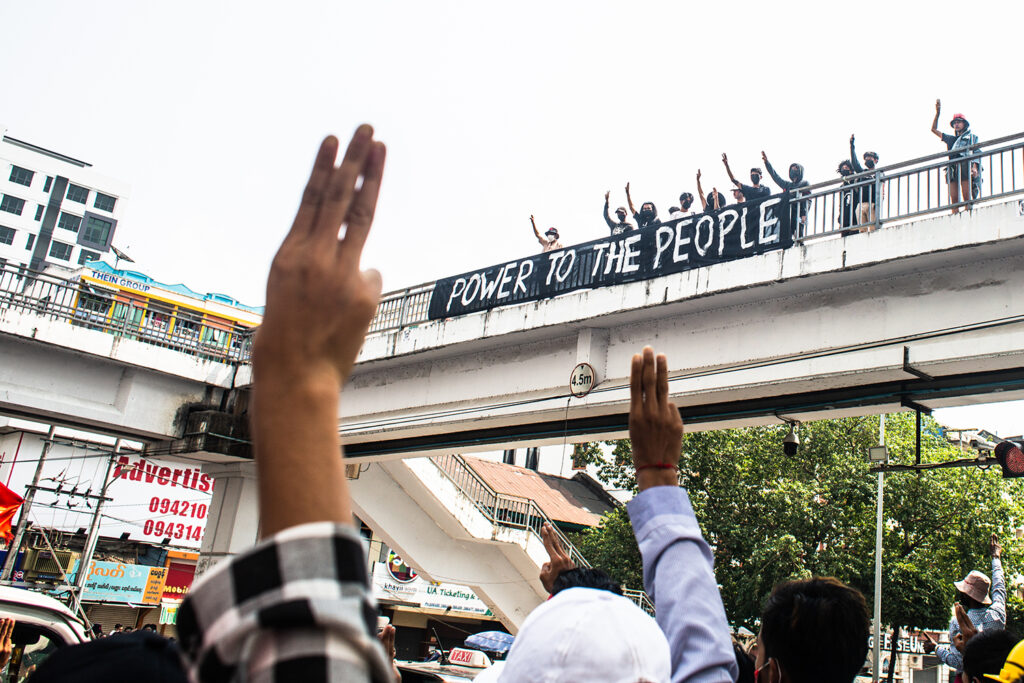

In Yangon, banners of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions hung in public places declared, “Take down the fascist army and bring in a new society.”

Ma Nay Nay*, a GSCN committee member, said strike groups across the country had formed strong networks and consulted each other on when to hold protests and what slogans to adopt.

“GSCN is a multi-ethnic strike group, so we prioritise ethnic and federal issues, while other groups have their own objectives. In early 2021 there were lots of different campaign slogans and strike calls made by the people, but later on our groups would agree on a common direction,” she explained.

“For example, on Anti-Fascist Revolution Day, the GSCN called for the dissolution of the fascist army, progress on federalism and opposing the fascist elections. Other groups supported our calls thanks to the strong connection between our strike committees,” she added.

Some slogans in particular have resonated with the public, such as, “Who are we? We are the people of Yangon”, and, “The mountains and land are now united”, referring to the solidarity in the struggle against the junta between the ethnic minorities, many of which live in mountainous areas, and the Bamar, mostly inhabiting the central plains.

“You can see how these protests and slogans are popular with the people and how they are playing an important role in the revolution,” Nay Nay said.

Strike committees also jointly discuss which commemorative days or particular events – such as military atrocities – merit protests.

These include Martyrs Day, Independence Day and the anniversary of the February 2021 coup, as well as the devastating air strikes on Chin and Kayin states in recent months, and the death of a welder from self-immolation outside a government office in Mandalay Region’s Kyaukpadaung town.

The “no going back to 2001, 2002” hand-written suicide note left by the welder Ko Aung Aung on the first anniversary of the coup was also adopted as a powerful slogan. The years 2001 and 2002 reference the dark days of the previous junta, where Myanmar citizens didn’t have regular electricity, access to internet or mobile phones, and lived in fear of the military regime.

When the junta executed four prisoners in July last year, including former lawmaker Phyo Zeya Thaw and veteran pro-democracy leader Ko Jimmy, strike groups responded with the slogan, “Martyrs never die.”

Creative protest ideas are at work too. The general strike of August 8, 1988, known as the 8888 Uprising, was marked last year by people writing the number 8 on their umbrellas in central Yangon. Youths have also distributed wrap-around longyis with slogans written on them.

From strikes to armed struggle

In the initial weeks following the coup, before the army started shooting protesters in the streets, slogans appeared at random, the most frequent being “We reject the coup”, “We want democracy”, “Free our leaders”, “Justice for Myanmar” and “Save Myanmar”.

Then government employees from various departments started using the slogan “Join the CDM” to promote the Civil Disobedience Movement, a mass strike by government staff aimed at incapacitating the junta. Celebrities and social influencers contributed by joining demonstrations outside government offices that were still functioning, while railway and forestry workers, doctors and lawyers organised themselves in groups to protest on the streets as part of the CDM.

“We designed and distributed placards like ‘Join CDM’ and ‘Support CDM’, so that lots of people would carry the same banners, reinforcing the message for the world’s media to show our country opposes the military,” said activist Ko Ye Aung.

When the military launched its bloody crackdown, Ye Aung felt he had to join the armed revolution, while his friends launched urban strike groups such as Yangon Revolution Force and Octopus. Some were arrested during protests and remain in prison.

“I decided to take up arms and fight back against the army, while my friends have chosen to continue their strike actions and fight alongside the public. We want the people to know that every protest and every slogan preserves hope for the revolution, which young people are risking their lives for,” Ye Aung said.

Sithu, a member of a group called Yangon Guerrilla Strike, recalls what he claims was the very first flash protest in Yangon, at noon on April 23, 2021, organised by the General Strike Committee.

A group of young people suddenly appeared on Anawratha Road in the heart of the city, despite the presence of military vehicles and police patrols in the area. Four young activists held up a black banner with the words, “Who are we? We are the people of Yangon”, while others shouted slogans from an alley behind them.

Bystanders became protesters and joined in, clapping and cheering. The protest group of about 100 people reached the top of Shwe Bon Thar Road, then stopped and shouted slogans. A young man, wearing a black shirt and with his face covered, climbed onto a stool and delivered a speech against the military dictatorship. Then the crowd swiftly disappeared into the alleys.

The words on the black banner “became a popular slogan among the public, and guerrilla strikes continued”, Sithu explained, going on to describe how strike committees and other groups consulted with each other so that slogans and objectives would go nationwide at the same time.

As protests went on, the army responded with more violence, ramming crowds with vehicles, opening fire and making arrests, Sithu said.

Flash mobs and other forms of guerrilla protest tend to be prompted by particular developments, he said. One example was a flash mob that gathered on December 5, 2021 on Panpingyi Road, in Yangon’s Kyimyindaing Township, to declare support for Myanmar’s ambassador to the United Nations, U Kyaw Moe Tun, who has stayed loyal to the civilian government ousted by the coup.

Their slogan that day was, “UN, prove you exist for justice”, to demand that it reject the military’s attempts to replace the envoy with a junta stooge. But before the protest got underway, a military vehicle drove into the crowd, seriously wounding two reporters, sending one of them to a coma that lasted for a month. Twenty-seven people were arrested, and last month 13 of them were sentenced to three years in prison.

“The Papingyi Road action is proof that every time we stage a protest, we have to take risks and pay the price,” said a member of Octopus who was arrested that day and later released.

The current focus is opposing the military’s plan for an election, having dissolved the main political parties that refused to register for it. No date has been set for the vote, but the movement has already come up with slogans like, “Oppose the fascist election, go ahead with the Federal Democratic Charter” – referring to an interim document drawn up by resistance leaders after declaring the military-drafted 2008 Constitution void – and “Oppose the fascist election and demolish the three pillars of military power”, in reference to the armed forces, its business interests and its control over the bureaucracy.

“There may be new slogans depending on the situation, but the current call is to oppose the fascist election of the fascist army,” said Ma Nay Nay, a GSCN committee member.

*denotes a pseudonym for safety reasons