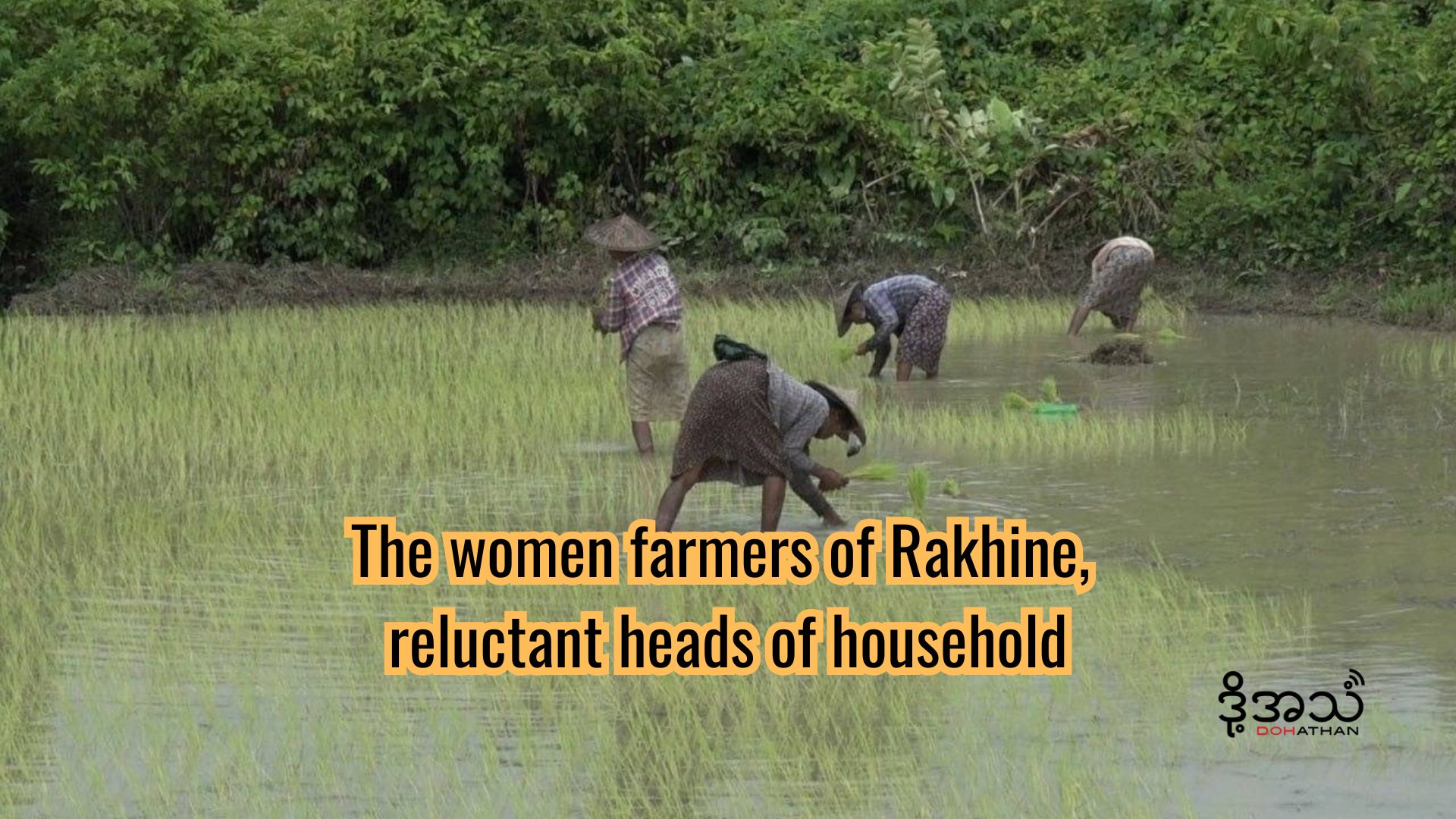

The Ministry of Information regularly arranges trips to northern Rakhine State for journalists and interesting encounters occur when their minders’ backs are turned.

By KONRAD STAEHELIN | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

ALL IT TAKES is a quick turn around a corner to evade the scrutiny of the minders and get a better understanding of the whole picture.

“Please, sir, you need to know that we have been lying to you all along because the government employees are listening,” the young man told Frontier. “We are afraid of repercussions if we don’t say what they want us to say. We don’t have a choice. I am sorry.”

It would be irresponsible to publish the young man’s name or say where in northern Rakhine State that the encounter occurred.

Furtive conversations with journalists are not what the government-appointed commission headed by former United Nations secretary Mr Kofi Annan had in mind when it recommended that “the Government of Myanmar should provide full and regular access for domestic and international media to all areas affected by recent violence – as well as all other areas of the state”.

Support independent journalism in Myanmar. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The recommendation is one of 88 in the final report that the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State released on August 24, 2017. In the early hours of the next day the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army launched a series of coordinated attacks on security posts in northern Rakhine, triggering a response from the Tatmadaw that sent more than 750,000 Rohingya fleeing to safety in Bangladesh.

A group of Rohingya men stand beside police officers in Nyaung Chaung village near Maungdaw town. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The continuing repercussions of the Tatmadaw’s “clearance operation” include the January 23 ruling by the International Court of Justice at The Hague that imposed on Myanmar most of the provisional measures sought by The Gambia in the case it brought under the 1948 Genocide Convention. The measures include requiring Myanmar to take steps to prevent genocide from occurring against the Rohingya community that remains in the country.

Instead of complying with the Annan commission’s recommendations and allowing journalists to assess the situation in northern Rakhine themselves, the Myanmar government tries to convey a narrative that reflects its perspective. It wants the world to believe that the Rohingya community is safe – or, if it is not safe, that this is the fault of the Arakan Army. It’s a position that is heavily contested by human rights groups.

In an attempt to portray its version of the situation to journalists, the Ministry of Information organises tightly planned trips to northern Rakhine that are conducted amid heavy security. Frontier was among the media outlets, along with Al Jazeera, BBC Burmese, Radio Free Asia, state broadcasters MITV and MRTV, and state-run newspapers that participated in such trip in late January.

Rakhine grandmother Daw Aye Thein Nyo, 68, with her grandson, Mg Naing Lon Soe, 4, at the entrance to a bomb shelter dug into a hill behind their house in Myoma Zayti Taung village, Buthidaung Township. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The three-day trip included visits to Rohingya and Rakhine villages in Maungdaw and Buthidaung townships that had been most affected by violence. Villagers were summoned by the dozen to attend meetings and answer questions. For participating journalists committed to professionalism and the concept of a critical media, these contrived meetings could not have been more bizarre.

During a visit to the Rohingya village of Nyaung Chaung, about three kilometres southeast of Maungdaw town, residents told Frontier that they felt unsafe. Asked what or whom they feared, the villagers answered with silence and uncomfortable smiles.

Government officials took notes and several heavily-armed Border Guard Police stood by. “They can’t answer,” said a translator employed by the government. “You are asking a very difficult question.”

In another encounter, a middle-aged Rohingya man told Frontier, as officials and members of the security forces listened, “Thanks to the Tatmadaw, we feel safe here.” Five minutes later, the officials had turned their attention elsewhere and the man had a different message.

“We obviously feel a lot of grief about what the army has done and continues to do to our people,” he said. The pursuit of truth in such situations requires a constant cat-and-mouse game with officials.

typeof=

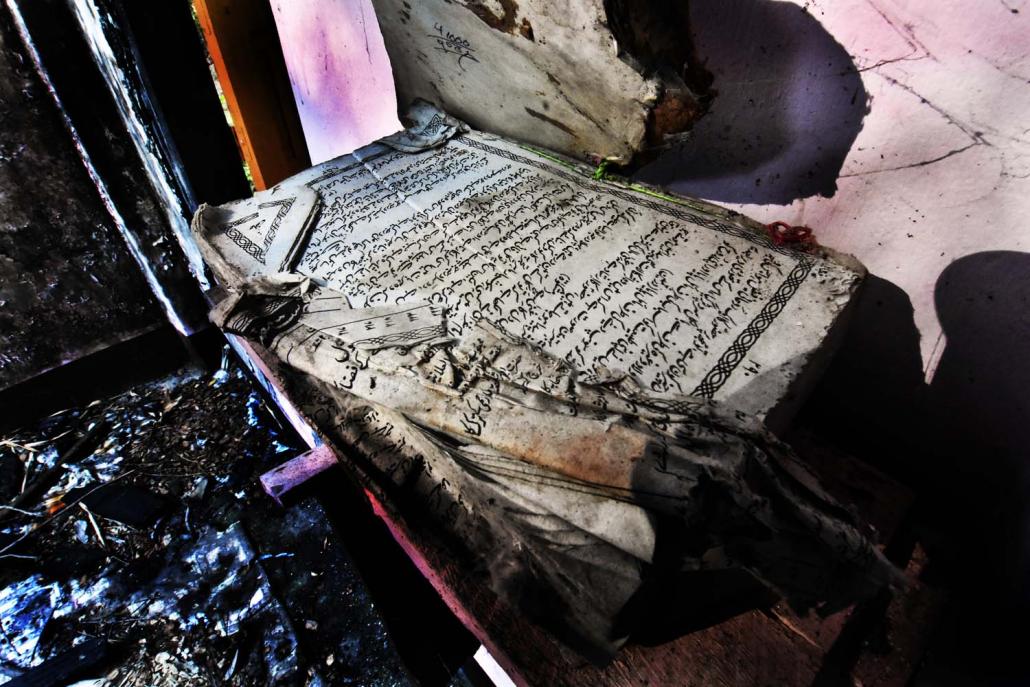

A ransacked and abandoned mosque near the Muslim village of Padin, south of Maungdaw. The village once had a population of 5,000 but now has just 200 residents. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

A change of itinerary

The fighting in Rakhine between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw is claiming the lives of both Rohingya and Rakhine in the north of the state. The AA and the Tatmadaw often blame each other for incidents that claim civilian lives.

On January 25, a few days before the press tour, artillery fire hit the Rohingya village of Kin Taung in Buthidaung Township, killing two women, one of whom was pregnant. The Tatmadaw rejected accusations from a Rakhine Hluttaw lawmaker, a villager and the AA, that it was responsible. The Tatmadaw confirmed the deaths but blamed the AA.

The village had been included on the press tour’s itinerary but was scrubbed after the incident. It’s possible the visit to the village was cancelled for safety reasons.

However, it is highly unlikely that the Tatmadaw and the AA would have clashed when they knew there were foreigners in the area. Perhaps the visit to the village was scrapped because the incident there shows that the Rohingya are not safe, regardless of who carries out attacks. Asked about the change of itinerary, ministry officials gave no explanation.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

In the village of Thit Yin, the journalists were shown a kindergarten for Rohingya children sponsored by the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF. There were sweet scenes of children singing and playing. “See? They’re not in any danger,” seemed to be the message.

No matter how determined the journalists’ minders were to show people living in peace, a different story often emerged. In the Rakhine village of Myoma Zayti Taung, there were bunkers in the back of a family compound. An elderly woman indicated that they were used during air raids. Only one side in the conflict in Rakhine has warplanes and helicopter gunships.

Death is everywhere in northern Rakhine, for Buddhist Rakhine and Muslim Rohingya alike. It is almost impossible to argue that the Tatmadaw is not responsible for most of the violence. The Annan commission was clear about the importance of unfettered media access to areas of Rakhine affected by violence. What is instead occurring looks more like an attempt to cover up the truth.