USDP candidates and supporters spread conspiracy theories about the ruling party colluding with Muslims against Buddhism, which may have encouraged violence against NLD members.

By BANYAR KYAW, PHONE HTET NAUNG, ALEX BEATSON, ANDREW NACHEMSON | FRONTIER

In late October, U Myo Win Soe was killed in Sagaing Region’s Kantbalu Township after a clash with supporters of the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party. It was the culmination of weeks of violence on the election campaign trail between the USDP and the ruling National League for Democracy, which Myo Win supported.

“He was a calm person,” said his sister, Daw Wai Mar Soe, who claimed her brother was beaten while trying to protect children from violent USDP supporters. “My brother said not to threaten underage children. Then they replied, ‘beat the adult’,” she told Frontier. He was taken to a hospital with severe head injuries before being discharged.

“When we brought him home, he could not speak properly, and his ear was bleeding. He vomited twice,” she said. Two days later, he was dead.

The October 22 incident came after multiple clashes that left other NLD supporters hospitalised and property destroyed. Although the USDP and the NLD blamed each other for the incidents, video footage tends to show USDP supporters instigating the violence, often chasing NLD counterparts while wielding large sticks.

Although the Union Election Commission is still certifying the results of the November 8 election, it is already clear that the NLD has won a landslide victory and taken most of the USDP’s remaining seats outside of Shan State, where the USDP is set to keep its status as the largest party. A humiliated USDP has rejected the results of the vote, alleging widespread fraud, and demanded that it be held again with Tatmadaw assistance.

There is concern that the party’s refusal to concede defeat could result in some of the same deadly violence seen during the campaign period. These campaign brawls, which were confined to USDP-NLD rivalry in the Bamar-majority regions, are a largely novel phenomenon in Myanmar elections and have had analysts reaching vainly for explanations. While there are likely multiple factors at play, Frontier has identified an upsurge in hateful rhetoric among pro-USDP networks on social media in the weeks before the vote that may have helped to incite or justify violence against NLD supporters.

Disinformation and hate speech shared by USDP candidates and their supporters on Facebook had sought to portray the NLD as being in a conspiracy with Muslims, alleging they posed an existential threat to Myanmar Buddhism. This trope has had the added effect of placing Muslims, already a vulnerable group, dangerously in the middle of party rivalry.

USDP candidate U Soe Soe Tun, who was defeated in the race for the Mandalay Region Hluttaw seat of Kyaukse-2, on September 23 made a post on Facebook in the form of a fictional conversation between a young, undecided voter and a group of USDP supporters. The post falsely claims that the NLD receives “millions of dollars” from the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and makes xenophobic attacks on State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi for marrying a foreigner.

“What kind of person would you be if a Myanmar woman married an Englishman and had a child? You can’t say what race he is, so it’s like losing his race,” the post says. “When the race disappears, so does the religion.”

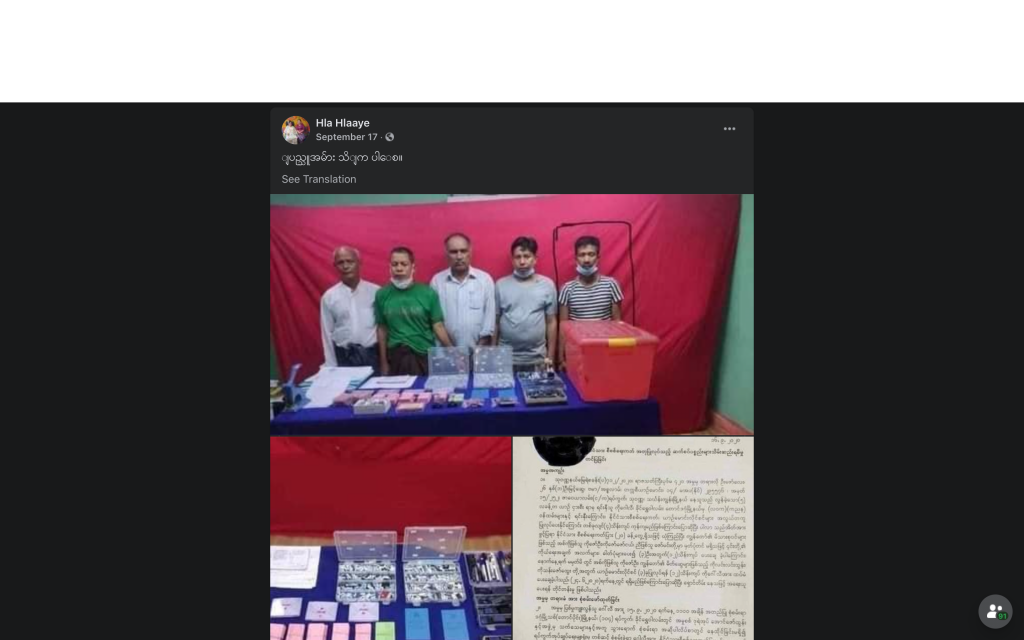

USDP candidate Daw Hla Hla Aye, who failed to win the Pyigyitagon-1 seat in the Mandalay regional hluttaw, also shared a racially charged post claiming that a group of men had been arrested for making fake identification cards for “illegal Bengalis”, a derogatory term for Rohingya that implies they are all illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. The unverified post also claims that the NLD was aware of the fraud and allowed it to continue. The post was first made by an account that mainly promotes the military, and especially Tatmadaw commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

Online monitoring group Loka Ahlinn said 188 posts relating to race and religion were made by the 99 political pages under observation between September 8 and October 7, the vast majority of which were negative. The USDP was the main propagator of this racially charged content, making 40 such posts in that time period, followed by the newly formed People’s Pioneer Party with 25.

USDP spokesperson Nan Mya Mya Mie Mie Zaw was one of the most persistent spreaders of this content, once calling Aung San Suu Kyi “a traitor of the state”.

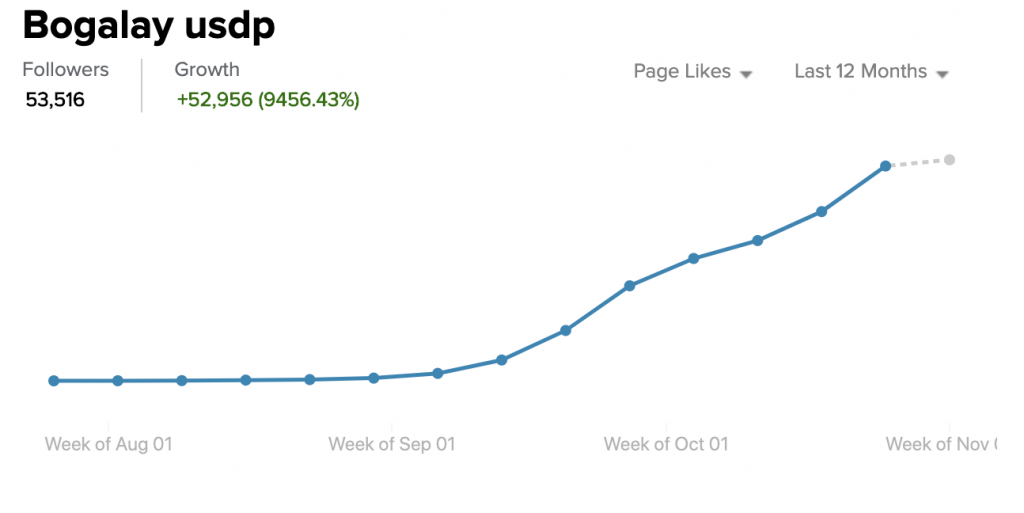

Pro-USDP Facebook groups have also been a breeding ground for hate speech and disinformation. Frontier found one particularly egregious group, called Bogalay USDP, which was removed entirely from Facebook after repeatedly sharing threatening and bigoted content that sometimes seemed to call for violence. One post, with over 1,000 shares and nearly 5,000 likes, said “we will learn the Dharma under the boots of the military, instead of the Kalar language under the [high]heels.”

References to high heels are commonly associated with Aung San Suu Kyi. Another accused Aung San Suu Kyi of “destroying the hearts and minds of Buddhists”. “Remember, this is our country, our land. I cannot be patient if you attack our race and religion,” it said. This post had nearly 2,000 likes and over 1,700 shares.

The Bogalay USDP group’s interactions, followers, and post activity all sharply increased at the start of September as the election neared. Between October 18 and October 24, it had over 575,000 total interactions and in the last week of October it made more than 2,600 posts.

Facebook said its “advanced automated enforcement technology” took down the group for “repeated violations of our Community Standards”.

The Burma Human Rights Network, a United Kingdom-based human rights group, also found rampant hate speech and disinformation circulating on Facebook, most of which “alleges conspiracies between the NLD and Muslims”. A BHRN report published on November 4 warned that “the hatred lingering after the election will easily be used to justify mass violence and conflict”.

One post found by BHRN that had more than 1,300 shares said the November 8 election was more than a contest between the NLD and USDP. “It is like a final match for the Buddhists,” it said. “If we lose this time our entire generation will be wiped out.”

U Kyaw Win, director of BHRN, said associating the NLD and Muslims is a “very dangerous narrative created by USDP supporters” which had likely inspired the attacks on NLD supporters.

Election-related violence also erupted in Mandalay Region’s Meiktila Township, the site of savage anti-Muslim violence in 2013, and a USDP stronghold until the election, when it lost all four seats to the NLD. As of publication, the USDP candidates have refused to accept the results, in line with the party’s central policy, and are calling the vote illegitimate.

In September, video footage showed USDP supporters wielding large sticks and throwing rocks at the homes of NLD supporters. On October 26, a man was stabbed, and a video appeared to show USDP supporters again instigating violence, chasing NLD counterparts with large sticks.

In a group called “Meeting Place for Meiktila Natives” which has since been removed from Facebook, a USDP supporter seemed to call for violence the next day. “We will conquer the township in the final battle,” said the now-deleted post. “They might bring stones, sticks, knives and weapons. If anyone does not want to see bloodshed, then other parties should not try to disrupt us.”

NLD spokesperson U Myo Nyunt declined to comment on the USDP’s internet activity but did say that the pro-military party “is using force” and is “not willing to control their supporters”.

As Loka Ahlinn found, it was not just USDP members who were spreading hate that could incite violence. Saw Yu Mar, a People’s Pioneer Party candidate who was unsuccessful in the race for the Pyithu Hluttaw seat of Thegon in Bago Region, shared a picture of an incendiary sign on October 1 that read: “Message to the patriots: Wake up brother, sharpen the knives. The evil race and empty-minded Myanmar people are betraying our country and our land. Let’s give a lesson to them!”

Another post, by a supporter of the National Democratic Force, a party founded in 2010 by breakaway NLD members that is now allied to the USDP, claimed that the “lion” was under threat by the NLD, a reference to the USDP’s logo. “We, the bamboo hat, have to gather and store knives and sticks,” the post read, referring to the NDF’s own farmer’s hat logo.

U Aung Htay, an administrator of the Karbo village tract where Myo Win Soe was fatally beaten, said the USDP supporters had arrived that day carrying “sticks and knives”.

“I never thought such violence would happen and, in the past, such violence has never happened in this area,” he said, speaking before the election. Aung Htay said people were also worried about post-election violence. “I worry about it, too,” he said.