Since the coup, security forces have protected the wealthy and well-connected in the capital, and left everyone else to deal with a rising crime wave on their own.

By FRONTIER

State security forces in the nation’s capital have largely kept protesters off the streets, but they’ve been less successful at combating what residents say is a surge in crime due to poverty and desperation.

The coup’s greatest impact on ordinary life in Nay Pyi Taw seems to be the devastated economy and the problems that come with it. Political instability and conflict due to the February 1, 2021 putsch have paralysed the banking sector, sent the value of the kyat plummeting, and prompted many foreign investors to head for the exits.

“It’s become harder to make a living since the military staged a coup,” said a woman from Zabuthiri Township’s Wunna Thedi ward, adding she is seeing rising levels of property theft throughout the city.

Her own motorbike was stolen in mid-January, despite being locked up with a metal chain. She has filed a complaint to police but said she has little hope of getting it back.

“Anecdotes about theft and robbery from all over the city are being posted more and more on Facebook. You see it on the local news, too,” she added.

Frontier was unable to request crime statistics from the police for security reasons. But locals agree that soldiers and police seem to have little interest in stopping or solving petty crime: they are focused instead on ensuring protests don’t return, and on protecting themselves, their bosses and wealthy retired generals from armed resistance.

In the so-called “Row of Six Mansions”, where the palatial homes of the Tatmadaw’s retired leaders line Taw Win Yadanar Road in Pobbathiri Township, security officials have installed themselves behind sandbag bunkers. Each of the three entrances to Taw Win Yadanar Road are cordoned off in barbed-wire, and nobody can enter without permission.

The street is currently home to former dictator and retired senior general U Than Shwe, former military-aligned president U Thein Sein and U Shwe Mann, a former general and MP, among others.

Soldiers and police are similarly staked out at major junctions throughout the city where protests were held immediately after the coup, despite residents describing the capital as generally free of political protests or violence over the past year.

“We do not hear bombs exploding like in other parts of Myanmar – we don’t have to worry about that so much,” a resident of Pyinmana Township said. “But we have to be vigilant about thieves.”

Do not enter

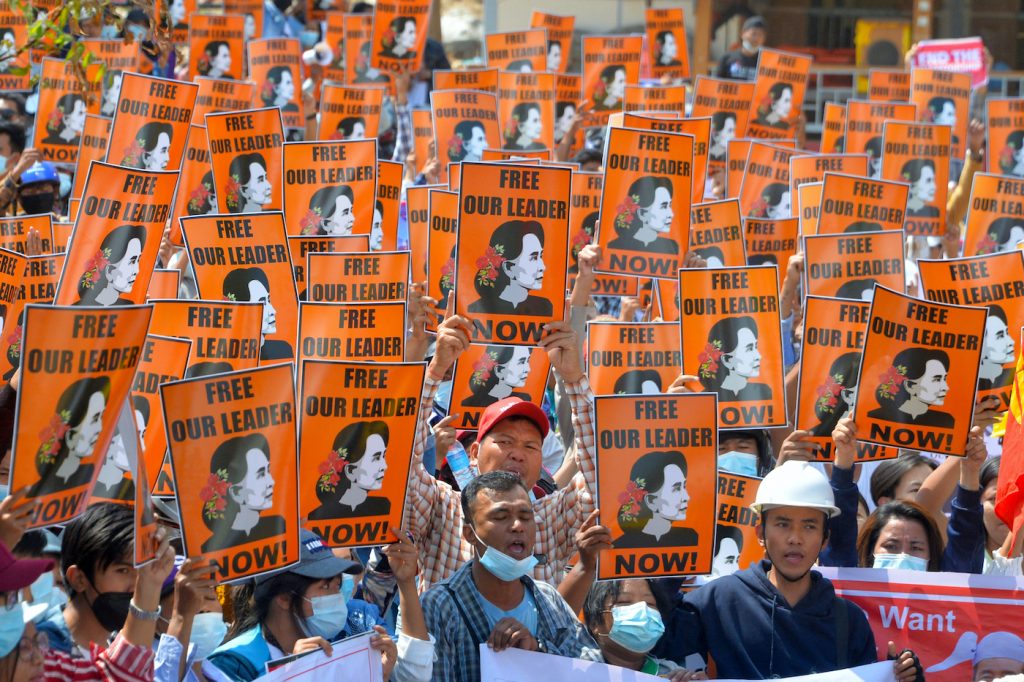

Immediately after the military launched its coup by detaining recently elected MPs and top officials from the National League for Democracy as they prepared to convene for the inaugural session of the new parliament, it turned its attention to locking down the capital. By 6am, police and soldiers were stationed at the city’s major junctions and gathering places.

Four days later, on February 5, residents gathered at the Thapyaygone Roundabout, located along the Pyinmana-Taungnyo Road in Zabuthiri, for Nay Pyi Taw’s first public protests against military rule. Four days after that, a soldier shot into the crowd and killed 20-year-old Ma Mya Thwe Thwe Khine, the first known casualty of the burgeoning national protest movement. By the end of February, protests in the capital had been largely quelled through mass arrests.

Today, five police trucks remain permanently deployed at the protest site, and a section of the Pyinmana-Taungnyo Road surrounding it is blocked off with barbed wire. Only military vehicles are permitted to pass.

“There are no more public protests. I don’t know why the Thapyaygone Roundabout is still closed,” said a frustrated Zabuthiri resident, who also works nearby within the township. “It’s very inconvenient for the people that have to go around to the other road [to get to work].”

The barricade was briefly removed during Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen’s visit in early January and replaced by Cambodian flags, but the barbed wire returned immediately upon his departure.

The streets in front of the Shwenatha football ground at the main entrance to the township – also the site of protests in the weeks after the coup – remain blocked as well. Cars cannot enter, and motorbikers and cyclists must get off and push their vehicles by hand after showing proof of their destination at military-manned checkpoints.

But the military’s presence is perhaps most heavily felt in areas surrounding government buildings, including the Pyinmana-Taungnyo Road entrance to Pyigyizaya Street, which is home to the residences of many senior government and parliamentary officials, including the President’s House. All are now occupied by regime leaders and appointees, safely ensconced in stately homes sheltered from the economic devastation outside.

Like at the football grounds, since mid-February cars are barred from entering and motorbikers and cyclists must show proof of their destination to armed guards stationed by the nearby Food and Drug Administration office. If allowed to pass, they must then push their vehicles by hand.

One of two entrances to the national parliament, the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, has been permanently closed, while security has been stepped up at the other. Only civil servants employed in the hluttaw are allowed to enter.

“The number of security guards has increased,” said one woman, a former hluttaw staffer who worked for two months after the coup before quitting to join the Civil Disobedience Movement. “In the past, they never checked our lunches. After the coup they would open everyone’s lunch boxes and check them.”

On days that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi appears in court, beginning around 8am, soldiers and police guard the roads around the Nay Pyi Taw Council building, where she and deposed president U Win Myint are being tried in a special court. The regime has not disclosed where Aung San Suu Kyi is being held, and no one knows the route she travels to the court.

Security is tightened even further on the days when sentences are handed down. Three police trucks are deployed along the road leading to the Dekkhina district court.

Security is also tight at the toll gate at Shwe Pyi Taw that marks the main entrance to the capital. Officials check all passengers, whether in public buses or private cars, inspecting their IDs and the recommendation letters from ward and village tract administrators that are required to enter the capital. Sometimes they ask questions and search travellers’ belongings.

Aung San Suu Kyi has already been sentenced to six years’ imprisonment on five separate charges and still faces at least 12 further cases that could carry a prison term of more than 100 years. Win Myint has been sentenced to two years on two separate charges and faces another six cases.

Ward administrators have also stepped up the checking of guest lists in the city’s hostels and dormitories, and hosting visitors has become increasingly difficult.

“Our dormitory’s family lists have been checked twice already, but we haven’t heard of any searches or arrests,” a dormitory owner in Zabuthiri’s Thapyaygone ward told Frontier.

The only places that seem free from barbed wire and permanent police patrols are in neighbouring Pyinmana, a town that predates the creation of Nay Pyi Taw.

Here, protests were so comprehensively crushed in the aftermath of the coup that a permanent, visible security presence is no longer needed.

Patrols were initially heaviest around the Rose Roundabout on Yazahtani Road, where some of the first protests in Nay Pyi Taw were held, but they disappeared around May last year. Likewise at the township’s No. 1 Basic Education High School, another former protest site.

“There aren’t really any places in Pyinmana where security police are permanently stationed anymore,” one resident told Frontier. “They only patrol at about 7pm and 8pm.”

‘Like the coup never happened’

Like just about everywhere else in Myanmar these days, Nay Pyi Taw has local armed resistance groups, including People’s Defence Forces aligned with the National Unity Government, but attacks in the capital have been much rarer than in some other parts of the country.

One 20-year-old who left her home in Pyinmana in April 2021 to join a rural PDF in a so-called “liberated area” under the control of an armed group, said PDFs could not expect much support from the capital’s residents.

“People in Nay Pyi Taw live their lives as if politics doesn’t matter. They don’t support the PDFs [financially], even though they could,” she said. “In this liberated area, PDF members have to wait a long time to get their hands on a weapon.”

The Nay Pyi Taw People’s Defence Force, or NPT-PDF, was formed on May 5, 2021, by residents of eight Nay Pyi Taw townships. The group claims to have carried out eight operations since its founding, between August and October, killing 39 soldiers and losing two of their own.

Verifying these numbers is nearly impossible, however, and many observers believe PDFs are inflating the number of soldiers they’ve killed while downplaying the number of fighters they’ve lost. What is certain is that attacks have been fewer in the capital than elsewhere in the country – likely owing to the military’s near-total lockdown of the city.

“There are a lot of checks at the Nay Pyi Taw toll gate. When I left Nay Pyi Taw, I was checked carefully. It’s more difficult to carry out operations in Nay Pyi Taw than anywhere else,” the 20-year-old PDF fighter said.

Official spokespersons for the NPT-PDF refused to speak to the media for “security reasons.”

The group has allied itself with PDFs in Demoso, Moebye, Pekon, Shan Taung and Loikaw – all in neighbouring Kayah and southern Shan states – according to an August 2021 statement the group posted on its Facebook page.

The NPT-PDF said it welcomed soldiers who wish to defect from the military, and will provide them with rewards and necessary security assistance. Other PDFs and armed groups have similarly offered rewards to soldiers and police who defect with their weapons.

However, the shift to armed resistance seems to have had minimal impact on the daily lives of residents in the capital.

“In Nay Pyi Taw now, it’s like the coup never happened. Children are attending schools. Restaurants are full of customers,” said a man who owns a shop in Pyinmana selling second-hand phones. But that doesn’t mean the city has escaped the economic troubles plaguing the rest of the country, he added.

“People are suffering economically. I used to display over 50 phones in my shop but now I can no longer afford so many,” he said.

Indeed, economic hardship – and the troubles that come with it – emerged as the major theme in conversations with residents around the city. The World Bank says the economy likely contracted by 18 percent last year, and is barely expected to grow in 2022-23.

“With so many people’s livelihoods hurt, many are turning to theft,” the Pyinmana Township resident said. “There are also more gambling dens now.”

“Nay Pyi Taw is silent [of fighting and protests]. Whether this is because people are afraid or because they’re just getting used to living this way, I don’t know,” said a 40-year-old woman who lives in the Thapyaygone area. “But under military dictator Min Aung Hlaing, life isn’t easy for anyone – under him, nothing is good.”