Even as factories close and many people stay home, air pollution in Yangon has remained stubbornly bad, and the agriculture sector may hold the answer.

By EAINT THET SU | FRONTIER

It has been described as a silver lining of COVID-19 – albeit one that is likely to be temporary.

Stay-at-home orders and factory closures due to pandemic have resulted in vast improvements to air quality in many of the world’s largest cities, including Wuhan in China, where the pandemic originated late last year. The Finland-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air has even estimated that declines in air pollutants may have prevented 11,000 deaths across Europe.

But in Yangon, there has been much less change to air pollution levels in recent months. At times, the city has had among the worst air quality in the world, according to monitoring sources such as Air Quality Index and PurpleAir.

The main sources of the particulate matter that contribute to air pollution in Yangon include vehicles, factories, generators, smoke from cooking fires – especially those using charcoal – and the burning of rubbish.

Support independent journalism in Myanmar. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

As in other cities, though, social distancing and other precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Yangon mean that fewer people are travelling to work, leading to much less traffic on the roads, and many factories have closed. The stubbornly poor air quality readings suggest that these are not the key causes of poor air quality, at least during the March to May hot season.

Air Quality Yangon, managed by a group of students from American University Yangon, is a platform that aims to create awareness about air pollution in Yangon, mainly on social media. Each day it posts two updates to Facebook using data collected from air quality sensors installed at different sites throughout the city, and information reported from a reference grade monitor at the United States embassy.

Farmer burn organic matter in Dala Township, Yangon Region, on May 8 in preparation for the planting season. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

AQY uses what’s known as the Air Quality Index – a standard for measuring a range of pollutants, such as the PM2.5 and PM10.

PM2.5 refers to particulate matter in the air that has a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometres, or about three percent of the diameter of a human hair. Particles smaller than 2.5 micrometres can penetrate deep into the lungs and may even enter the blood stream. The World Health Organization says the health effects of exposure to high levels of both PM2.5 and PM10 are well documented and include respiratory and cardiovascular illness, sometimes leading to premature death. Those with pre-existing lung or heart disease, as well as elderly people and children, are particularly vulnerable, it says.

The AQY page features a colour-coded chart to indicate air quality based on the level of particulate matter. It ranges from green, for good air quality (PM measured at 0-50), to yellow, moderate (51-100), orange, unhealthy for sensitive groups (101-150), red, unhealthy (151-200), purple, very unhealthy (201-300), and burgundy, hazardous (301-500).

Air quality data collected by AQY shows there has been only a modest decrease in particulate matter pollution in Yangon. The group told Frontier by email that many people wanted to know why air quality had not noticeably improved.

“We have received many comments and inquiries as to why the air has not gotten much better,” AQY said. “[The enquiries] state that with so many cars off the road and many factories shuttered, there should have been drastic improvements in the particulate matter pollution and why are we still seeing these ‘spikes’ in pollution.”

The group said there is evidence suggesting that the stay-at-home order in Yangon may even have contributed to pollution. It has received “many reports” from its followers of people burning trash and leaves in their neighbourhoods while being told by the government to stay at home. “One AQY-page follower posted a picture of ash falling from the sky during a period correlating to a high AQI. While our results and investigations are not definitive, we can say that there are other contributing factors to the particulate matter pollution and we believe that other major contributors are burning of waste and biomass [dry leaves and crop stubble].”

The group identified agriculture as a potentially key driver of Yangon’s poor air quality.

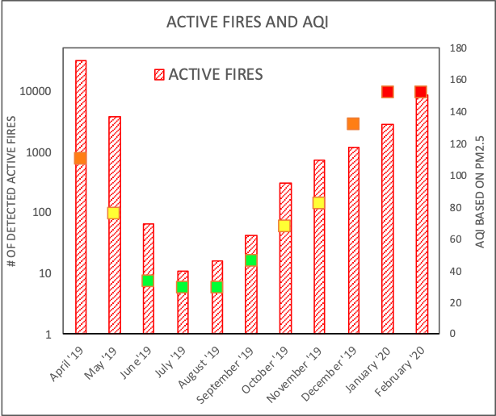

AQY shared with Frontier NASA satellite images showing that large numbers of fires are detected in Myanmar from January to May, when air quality is normally at its worst and rainfall is sparse.

“This corresponds to the dry season and is also the time one is likely to see crop-stubble burning,” the group said.

This chart shows the correlation between active fires and air quality. (Supplied | Air Quality Yangon)

The air quality then typically improves during the June-October rainy season, AQY said. The months after the harvest season from December to March are when farmers burn crop stubble. It is also when fire is used to clear land for shifting agriculture, known as taungya, in upland areas of ethnic states.

Dr Ohnmar Khaing, an agribusiness consultant, said the three main reasons why farmers burn stubble after the harvest are to clear weeds before the next planting season, kill pests in the soil or on crop residue, and to replenish soil.

“About 75 percent of the burning in Myanmar happens in hilly regions,” she told Frontier.

But Dr Tin Htut Oo, the chief executive of Agribusiness and Rural Development Consultants Co Ltd, said in the absence of any studies it could not be said conclusively that agricultural burning is the main reason for Yangon’s poor air quality.

Asked about burning that Frontier observed this month in rural Dala Township in Yangon Region, he said it was past the time when farmers would be burning off post-harvest, but they could be preparing to plant the monsoon crop by burning waste, such as straw, and plant residues.

Tin Htut Oo pointed to the burning of leaves and waste in suburban areas of Yangon and the regions surrounding it, including Ayeyarwady and Bago, as an overlooked cause of poor air quality.

Regardless, Ohnmar Khaing said there were alternatives to agricultural burning that could help to improve soil quality, including growing and applying grass-dominant pasture to the soil, applying organic fertilisers, and making productive use of crop stubble. In other countries, she said, crop stubble is being turned into a wide range of products, including environmentally friendly packaging and pellets for use in energy production.

However, she said lack of technology and knowledge were major barriers to adopting farming techniques that minimise the need for open burning.

Asked about the readiness of farmers to adopt alternatives to burning, Ohnmar Khaing said farmers were more concerned with other problems, like controlling pests. But experts were raising awareness about the impact of burning fields, she said.

“Maybe in five years’ time,” she said, “most farmers will have awareness [about the problems with] this burning tradition too.”