An emerging group of young film directors is delighting audiences with original creations that challenge a tired movie production formula little changed in decades.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

EXCITEMENT WAS building among movie fans for weeks ahead of the commercial release of the psychological thriller Nya (“Night”) last July. But the eagerly anticipated event nearly turned into a real-life nightmare for director Htoo Paing Zaw Oo, 31, who began working on Nya in 2014.

It happened to coincide with an outbreak of potentially deadly H1N1 influenza. The risk of catching the highly infectious virus kept ardent fans – and even some of Htoo Paing Zaw Oo’s relatives – away from his debut movie.

But as the H1N1 scare eased, audiences flocked to see Nya. It has not only turned a profit, but was even screened several times in Singapore in late April and early May – a rare achievement for a Myanmar-made film.

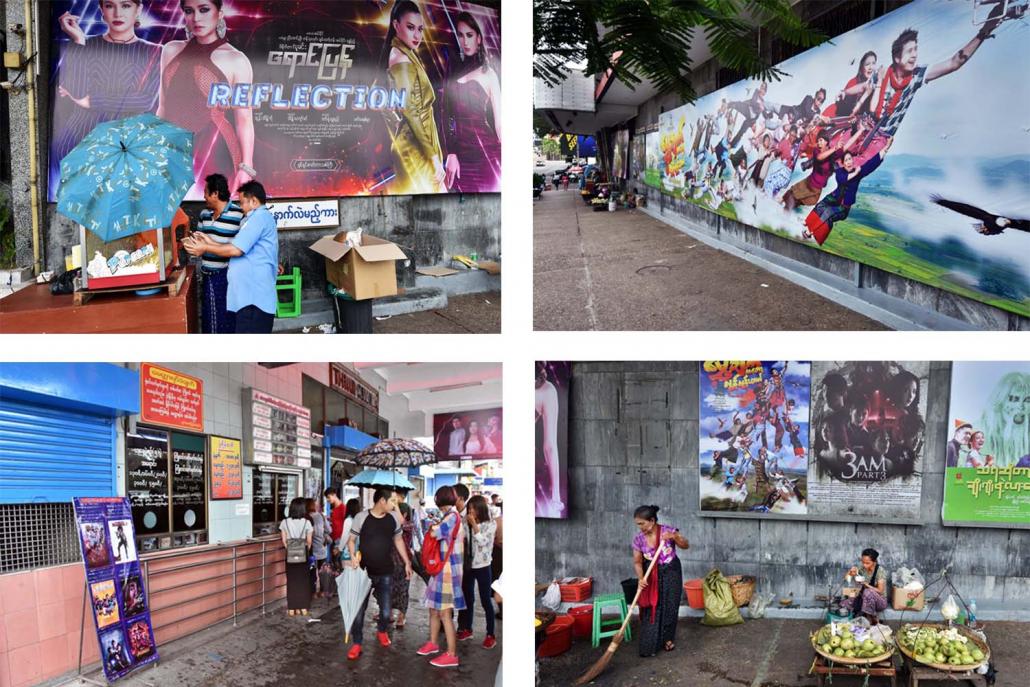

The box office successes of Nya and subsequent releases – the action drama Myet Hnar Pyin Myar (“Dimensions”), directed by Nyan Htin, 35, and Mudra Yae Khaw Than (“Mudras Calling”) by Christina Kyi – are being driven by audiences hungry for a new approach to movies that spurn the tired formulas of the past.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Critics say cinemas have been ringing with the loudest applause heard in decades, as audiences show their appreciation for the innovative productions.

Fans get the chance to meet the stars of Mudras Calling in Yangon (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

The success of these “new wave” films has laid down the challenge for the film industry establishment, which is increasingly seen as lacking imagination and more interested in making money than art.

Recently, a group of young movie fans has stepped up their Paw Kar Myar Yat (“Stop Silly Movies”) campaign against films and videos made by established directors and starring prominent actors.

“When great movies such as Nya come, they show that the reasons given by famous filmmakers and actors for not making good films are just baseless excuses,” a senior member of Paw Kar told Frontier.

(The campaign leaders seek to remain anonymous due to concerns that they might be prosecuted for online defamation.)

Paw Kar’s four founders – a poet, lawyer, part-time university lecturer and a student studying for a Masters in Political Sociology – say the movies that dominate the market often resort to cheap humour that can have a negative effect by reinforcing stereotypes.

It’s not unusual for these movies to have scenes ridiculing disabled people, or to make fun of differences in gender, ethnicity and religion.

“Making movies that laugh at these things needs to be denounced. It is shameful for society that this is happening. The script writers of silly movies keep writing screenplays that degrade those who have chosen their sexuality, or who have dark skin,” the Paw Kar member said.

Paw Kar blames the situation partly on an education system that fails to develop critical thinking. It says prominent actors are influential and when they deliver harmful or negative messages these are easily absorbed by audiences.

A director’s struggle

More than six years ago, Ar Kar left his high-income job as an IT technician in Singapore to follow his dream of becoming a film director. It was a struggle in the early years because a dearth of producers, who fund movies, meant that Ar Kar, 29, was unable to make the kind of movie he wanted.

Ar Kar left his high-income job as an IT technician to follow his dream of becoming a film director. (Supplied | ARKAR Production)

He didn’t give up. His company, ARKAR Production, made music videos and commercials, and he participated in independent film festivals. They included the Wathann Film Festival and the Art of Freedom Film and Music Festival, which were first held in 2011 and 2012, respectively, as the country was emerging from decades of military rule.

Ar Kar’s creations caught the discerning eye of some of the few producers keen to invest in movies made by emerging young directors. He got his first big break as a director with The Mystery of Myanmar: Beyond the Dote-Tha-Waddy, which has been praised by many moviegoers.

“The biggest challenge for this new production was having to jostle very hard to have it screened in cinemas,” Ar Kar said.

Cinemas owners prefer to preview movies in private before deciding to screen them. ARKAR Production had to wait a few months before a private screening could be arranged. The Mystery of Myanmar: Beyond the Dote-Tha-Waddy premiered in Yangon cinemas on May 4, months after Ar Kar hoped it would be released.

One problem is simply a lack of cinemas: decades of neglect mean many have closed or been sold off, and there are only 102 working cinemas left. There are no cinemas in Chin and Kayah states and the only movie house in Rakhine State, in the capital, Sittwe, is closing.

Of the working movie houses, about three-quarters are owned by the Mingalar Cinema Group chain, which can mean intense competition to arrange private-screenings with the company.

The opportunity to show their film on Mingalar’s screens can mean the difference between a crippling loss and a handsome profit.

untitled-2.jpg

Beyond the Dote-Tha-Waddy, which was released on May 4. (Supplied | ARKAR Production)

“Now we all just have to compete just to show our films [with Mingalar] first,” Ar Kar said. “If all stakeholders can work together on this, we wouldn’t need to rush … we can just focus completely on filmmaking.”

The stakeholders include the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization, which has pledged to help tackle the cinema shortage. Thailand and Malaysia each have at least 1,000 cinemas.

“We are trying to solve this problem,” MMPO vice-chairman U Zaw Min told Frontier. “Some cinemas are being built and in a few months I think the total number in the country could reach 150.”

Asked to assess movies made by the new crop of directors, Zaw Min said such a question was best answered by numbers from the box office.

“Their creations may be good, but there’s huge variation in what moviegoers like; some like sweet, some like salty and some may like spicy. Cinemas are guided by what audiences want to watch,” he said.

Ar Kar suggested the government support the creation of a fund for investors to finance the building of more cinemas.

However, the emerging young directors are concerned that expanding the number of cinemas may create more opportunities for makers of the low-quality films that have predominated until now.

It’s a concern that also troubles prominent director Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi. Although he’s not among the new bloods, since returning to Myanmar in 2003 he has also sought to create original, high-quality movies, as well as helping to train the next generation of filmmakers.

Movie posters on the wall of Thamada Cinema in Dagon Township. The lack of cinemas means directors have to lobby cinema owners for the chance to have their film screened. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

“I’d like to ask the movie industry what kind of films would it make if there were enough cinemas. Except for the very few new-blood directors, all the remaining directors will continue to make easy, silly movies,” Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi told Frontier.

To prevent this, Ar Kar suggests the introduction of a quality control system.

“Regulators like MMPO should set quality control standards under which movies are classified, otherwise the silly movies will continue to dominate the market,” he said.

‘Silly’ movies?

There’s a consensus among the new wave directors, critics and audiences about what meets the definition of a “silly movie”.

They tend have a weak story line, feature exaggerated scenes and use the same, unrealistic dialogue repeatedly. They are produced with minimal preparation and rely on a cast of stars to maximise audience appeal.

Plagiarism is also an issue, as many of these movies are based on foreign productions or those made in the glory days of the Myanmar film industry – before it lost its edge under the stifling censorship regime introduced after General Ne Win seized power in 1962.

Tar Tay Gyi, a copy of a Bollywood horror movie titled Kanchana, was among the prizewinners at this year’s Myanmar Motion Picture Academy Awards in Yangon in March. Some said the decision to give a prize to a copy film at the industry’s main annual event was unethical.

Emerging directors were disappointed by this year’s Academy Awards ceremony. They included Htoo Paing Zaw Oo, who was hoping to receive a technical award for Nya, but went home empty handed.

But many actors and directors have been angered by the Paw Kar campaign and the suggestion that the industry needs to be shaken up by a “new wave” of filmmakers.

Myanmar Motion Picture Organization patron U Soe Moe, 72, said some may be using the campaign to build their own popularity.

“If you can really produce good films, you will last a long time. The film industry is not just about one year. I’ve been here for over 50 years and won academy awards, and my movies have been shown in other countries. And in my experience, the new faces tend to come out frequently [but then] they disappear.

“So, how many decades will they [new wave directors] last, and how many awards can they get? These are the measures by which we should judge them. For me, at the moment, it’s still early to judge them. Time will tell.”

Interference

Veteran director Win Pe said the Academy Awards had never been on the right track since they were inaugurated in 1952.

“The key problem has been government interference in honouring the artists,” Win Pe said.

Another problem was that the government had allowed officials to sit on the selection board rather than experienced movie industry professionals, he said.

Win Pe said the situation had improved compared to previous decades.

“However, if compared with the film industry in other developing countries, we need hundreds of board members to finalise specific Academy Award titles and we also need to give audiences a bigger say in choosing the nominees,” he said.

Director Win Pe. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Ar Kar said the board needed to become more transparent and if it did not there was a risk another industry organisation would emerge to bestow awards.

Ar Kar said he accepted that the board had the authority to decide award winners but added that to avoid controversy it needed to be accountable and explain its choices.

The awards presentation night this year was attended for the first time by State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, accompanied by Minister for Information U Pe Myint.

In a speech at the event, Aung San Suu Kyi pledged government support for the development of the movie industry and also urged artists to strive to raise production standards to the levels achieved when she was a child.

The Myanmar Motion Picture Development Department, under the Ministry of Information, is the main regulator of the film and video industry and its tasks range from censorship to making DVDs.

Return of the golden days?

Veteran director Win Pe has encouraged the new wave directors to make up for lost time.

“They need to keep striving, to develop more awareness, to read more. They cannot walk at the same pace as their peers around the world; they need to walk much faster because we have been left behind for a long time,” he said.

The founders of Paw Kar reject claims by the makers of low-grade movies that their productions are a response to audience demand.

They said that because of a lack of education, many people did not realise that they were being exploited by those producing these types of films.

“The producers might say they willl just keep making these movies because they still have viewers. But … that’s not a very professional attitude.”

Yangon movie fan Ko Zaw Min Aung, 29, spurned Myanmar movies for a decade; he abhors the “silly movies”. But then, in late April, he watched Oo Pel Tamyin (“Deception”) by Christina Kyi. He described it as a satisfying entertainment experience.

“The makers of silly movies are cheating audiences by wasting their time,” Zaw Min Aung said. “The time that we give them – maybe one or two hours out of our day – is even more precious than the money we give them.”