Here they are, for better or worse: those who made headlines during 2017, from a beloved canine to political leaders and imprisoned journalists.

By FRONTIER STAFF

Illustrations JARED DOWNING

ko_ni_1.jpg

PERSON OF THE YEAR: U Ko Ni, lawyer and prominent Muslim

For many, January 29 was the date that any residual optimism in Myanmar’s “transition” to civilian rule was permanently shattered. A respected lawyer, scholar and adviser to Aung San Suu Kyi, U Ko Ni was on that day shot in the back of the head at point blank range on the outer concourse of Yangon Airport. Moments before, he had been cradling his young grandson. A taxi driver pursuing the gunman, himself a former bodyguard to the State Counsellor, was also killed before the assailant was subdued.

No words can convey the shock and outrage that fell upon the country’s legal and media fraternities in the aftermath of the murder. Many had considered him a mentor and a friend, and thousands attended his funeral. The motive for his assassination has never been satisfactorily explained. Police implied, unpersuasively, that the murder was racially motivated — Ko Ni was one of the most prominent Muslim figures in the country. Others have suggested his role in Aung San Suu Kyi’s elevation to de facto leader of the government, a workaround of the military-drafted constitution that prohibited her from taking the presidency.

Four people have been arrested in the murder plot and an interminable court case against them continues. The conspiracy’s ringleader, Aung Win Khaing, is still at large despite being spotted in Nay Pyi Taw in the days after the assassination. Three of the accused are former military officers.

assk.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, State Counsellor

For reasons that were sometimes out of State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s control, it’s been an “annus horribilis”. The Rohingya crisis has left her international reputation in tatters, despite her decision to seek sustainable solutions to the situation in Rakhine State by appointing the Annan commission. The violence that followed the August attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army in northern Rakhine – launched just hours after the commission’s final recommendations were released – has also created fresh strains in the already uneasy relationship between the government and the Tatmadaw.

The year began with the quest for peace and national reconciliation on Aung San Suu Kyi’s mind. She chose January 1 to open the National Reconciliation and Peace Centre in Nay Pyi Taw and marked the 70th anniversary of Union Day on February 12 with a symbolic visit to Panglong, where her father, Bogyoke Aung San, agreed a formula for federalism with ethnic leaders in 1947. The second 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conference in May ostensibly advanced the process by agreeing 37 points to be included in a future agreement, but also opened up rifts with both signatories and non-signatories to the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. As the year wore on, economic development – especially roads and electricity – increasingly became a priority for Aung San Suu Kyi, who already has her eyes on the next election.

Aung San Suu Kyi came under increasing criticism during 2017 over her management style, reluctance to delegate, tendency to micromanage and failure to groom a new generation of leaders. The use of 66(d) has raised doubts over her government’s commitment to freedom of expression and there has been disappointment among the media that she has not been more open and accountable. While April by-elections suggested support was mostly unwavering – the NLD won 9 of 19 seats – critics point to the lack of strong opposition and the party’s poor handling of a bridge-naming controversy that likely cost it a seat in Mon State. In 2018, the biggest challenges Aung San Suu Kyi faces will likely involve the peace process, the repatriation of refugees from Bangladesh and relations with the Tatmadaw.

Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Commander-in-Chief

It’s been a busy year for Tatmadaw leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. More fighting in northern border areas, another Union peace conference, a major operation in Rakhine State, tactical manoeuvres in the power game with the government and extended visits to India and China. There was also a trip to Austria and Germany in April, but Min Aung Hlaing won’t be returning to Europe any time soon: The European Union in October suspended invitations to the Tatmadaw C-in-C and other senior officers because of what it called the “disproportionate” use of force by the military in northern Rakhine after the August 25 attacks by Islamic militants.

Min Aung Hlaing has clearly resented the international criticism of the Tatmadaw over an operation that has broad popular support; when Britain suspended a training programme in September and Myanmar soldiers were sent packing at short notice, he responded angrily that the military would never send its troops there again. Reports that a large number of “Bengalis” had fled to Bangladesh were an exaggeration, he said in mid-October, when the United Nations put the exodus at about 530,000 people. An internal Tatmadaw investigation released on November 13 exonerated itself of accusations of widespread murder, rape and arson, saying there had been no use of “excessive force”. The US did not agree and joined the UN in declaring that ethnic cleansing was taking place. “Those responsible for these atrocities must be held accountable,” said US Secretary of State Mr Rex Tillerson after a November 15 visit for talks with State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the Tatmadaw chief. The foreign condemnation rankled. On November 29 thousands rallied in Yangon to show support for Min Aung Hlaing and the Tatmadaw operation in Rakhine.

On the peace process, Min Aung Hlaing was resolute that the key to success was for all armed ethnic groups to sign the so-called 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. His stand is being resisted by an alliance of seven armed groups headed by the nation’s most powerful, the United Wa State Army, which is demanding that the NCA be re-negotiated. A furious Min Aung Hlaing has accused non-signatories of blocking the people’s aspirations for a federal Union.

On the diplomatic front, Min Aung Hlaing visited China in November and thanked Beijing for its international support for Myanmar over the Rohingya crisis. The Tatmadaw chief will also be appreciative of India’s support. During his second visit to India in two years, in July, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, said New Delhi wanted to strengthen bilateral defence cooperation. India followed up in November when it began training a group of Tatmadaw officers for UN peacekeeping duties.

Atta Ullah, Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army leader

The communal violence in Rakhine State in 2012 hardened attitudes among young Rohingya weary of discrimination. Despair deepened in 2015 when the Rohingya were disenfranchised after the government nullified their temporary identity cards, losing their political voice, and a crackdown on people-smuggling across the Bay of Bengal ended hope of a better life somewhere else.

Ata Ullah, a Rohingya man born in Karachi and raised in Mecca, and other leaders of the group now known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, found a receptive audience when they began recruiting and training in northern Rakhine in 2012. It was time for the persecution to end and the Rohingya to become citizens, Ata Ullah said. Hundreds were trained, most with farm tools as weapons. The first attacks on security posts, on October 9, 2016, marked the emergence of what the International Crisis Group called “a new Muslim insurgency in Rakhine”.

The Tatmadaw was ready when ARSA launched a second wave of attacks on August 25, hours after the release of the final report of the Annan commission and its prescriptions for sustainable solutions in Rakhine. The military response to the attacks was ferocious. Ata Ullah announced a unilateral ceasefire on September 9 but the government said it did not negotiate with terrorists. The violence continued and so did the exodus of Rohingya to an uncertain future in Bangladesh. If Ata Ullah’s strategy in launching the August 25 attacks was to focus global attention on the plight of the Rohingya it was spectacularly successful, but at what cost in human misery for his people?

kofui_annan.jpg

Kofi Annan

The quietly-spoken Ghanaian with a reputation for strategic thinking seemed an inspired choice to lead the nine-member commission appointed by the government in August 2016 to propose lasting solutions to conflict, displacement and underdevelopment in Rakhine State. Mr Kofi Annan, 79, had devoted much of his 45 years with the United Nations, including two terms as its secretary-general, to trying to end conflict. The commission was needed “to heal all the wounds of our nation”, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said a few days later.

The commission’s appointment was the first serious attempt for a solution in Rakhine since Prime Minister U Nu created the short-lived Mayu Frontier Administration in 1961. There was hope and confidence over the appointment of Annan’s team of six Myanmar and three foreigners, but also criticism. The Arakan National Party condemned the involvement of foreigners in Rakhine affairs and there was irritation among the state’s lawmakers that they had not been consulted in advance about the commission’s appointment. The hope invested in the commission was shaken by the attacks of October 9 last year, but worse was to come. In a cruel twist of fate, or a deliberate act of sabotage, the optimism virtually evaporated in the aftermath of the second round of attacks by the ARSA on August 25, a day after the commission’s final report of 88 recommendations was released in Yangon.

The report was titled, “Towards a peaceful, fair and prosperous future for the people of Rakhine”. Annan acknowledged that the commission’s recommendations on citizenship and freedom of movement were “profound” concerns of the Rakhine population. “Nevertheless,” he continued, “the commission has chosen to squarely face these sensitive issues because we believe that if they are left to fester, the future of Rakhine State – and indeed Myanmar as a whole – will be irretrievably jeopardised.”

charles_bo.jpg

Charles Maung Bo

Cardinal Charles Maung Bo offered a trinity of realpolitik suggestions to Pope Francis when he met the pontiff at the Vatican ahead of his historic visit to Myanmar in late November. They all displayed an aptitude for diplomacy that Charles Maung Bo, 69, has often demonstrated since becoming the country’s first cardinal in 2015.

His suggestions also showed a determination to ensure the nation’s small Roman Catholic community remains uncontroversial at a time of rising Buddhist nationalism, though the advice to the pontiff to avoid using the word “Rohingya” during the visit did make headlines. The cardinal also suggested the meeting between the pope and Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, which took place soon after the visit began. There had been no dialogue between the church and the Tatmadaw for 60 years. “Now, a relationship has started and we hope the dialogue will improve,” the cardinal said.

The third suggestion reflected the cardinal’s efforts to support and promote interfaith dialogue and it resulted in the pope’s meeting with Buddhist, Christian, Muslim and Hindu leaders. Sometimes the cardinal feels a need to speak out, as he did in a September statement that defended State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi against criticism over her response to the crisis in Rakhine State. It was unfair and counterproductive to lay all blame on Aung San Suu Kyi, he said, praising her government’s initiative to appoint the Annan commission to propose lasting solutions in Rakhine. The situation in Rakhine was a tragedy that should never have happened and Myanmar needed to move “from a wounded past towards a healing future”, the cardinal said in the statement. “Let the lessons of the past enlighten our future. Peace based on justice is possible, peace is the only way.”

Ko Lawi Weng, journalist

“This is democracy in our country,” Irrawaddy journalist Ko Lawi Weng told reporters in July, gesturing to his handcuffs, partway through a tirade dripping with sarcasm and fury. The acclaimed journalist, a peerless reporter of Myanmar’s numerous civil conflicts, had been detained after returning from an anti-drug trafficking ceremony organised by the Ta’ang National Liberation Army in Shan State. He and two other reporters from DVB were held unlawfully at an army camp for several days before their transfer to police custody in Lashio.

Every stage of the proceedings against the trio made a mockery of the legal system. The defendants faced unlawful association charges for communicating with a group that had met with Aung San Suu Kyi in Nay Pyi Taw the previous month. Proceedings moved at a snail’s pace as prosecution witnesses from the military failed to appear at court. After two months in custody, charges were dropped against all three in a transparent attempt by the military to curry favour with the press as the devastating crackdown began in northern Rakhine State.

Many journalists had hoped for warmer relations with the NLD government than what they had weathered under the Thein Sein administration. Instead, more than a dozen reporters and editors have spent time behind bars in Myanmar this year. Foreign governments, rights watchdogs and local media associations have all warned of a fresh crackdown on press freedom.

U Phyo Ko Ko Tint San

If you’re going to illegally accumulate a cache of guns, it’s probably best not to pose with them on Facebook. The arrest of U Phyo Ko Ko Tint San, 41, in October marked a sudden decline in fortunes for the high-flying son of former sports minister U Tint San and chairman of the ACE Group of Companies. A well-connected fixture of Myanmar’s sporting community who regularly flaunted his playboy lifestyle on social media, he was arrested at Nay Pyi Taw airport after a search revealed there were two handguns and illicit drugs in a bag he was carrying. Subsequent searches of his family’s Nay Pyi Taw hotel and office in Yangon turned up an arsenal of high-powered weapons.

Perhaps signs of a fall had been coming: A month earlier, the football club Phyo Ko Ko Tint San owned, Nay Pyi Taw FC, had been expelled from the Myanmar National League for non-payment of players. Phyo Ko Ko Tint San claimed to police he had collected the guns with the intention of establishing a security company. How he managed to build up such a stockpile of weapons in the country’s capital remains unclear.

myo_ko_ko_san.jpg

Ma Myo Ko Ko San, beauty queen

An LGBT beauty queen and a soap opera superstar bear the joint distinction of becoming embroiled in Myanmar’s most absurd celebrity feud in recent memory. Ma Myo Ko Ko San, the 2014 winner of the Miss International Queen transgender beauty pageant in Thailand, was arrested in January on her return from Bangkok. She had been accused of administering a Facebook page spreading gossip about actress Ma Wut Hmone Shwe Yi and her alleged romantic dalliances with a number of prominent high-society men.

Fears had been raised for the safety of the model, who was detained in a male cell in Yangon’s Yankin Township. Myo Ko Ko San, who had stridently maintained her innocence, was released four days later after a judge concluded it was impossible for her to have been responsible for the salacious social media posts. The affair once again raised troublesome questions about the treatment of LGBT people in Myanmar, and shone a spotlight on the spiralling use of the Telecommunications Law to criminalise activity on social media.

U Than Myint, Minister for Commerce

It was the great missed opportunity. Get the clunkers off the roads and rectify a long-standing safety problem: right-hand-drive vehicles being driven on the right side of the road. Instead, the U Thein Sein government replaced all the old, right-hand-drive cars with… newer right-hand-drive cars. For several years there had been talk of restricting all imports to left-hand-drive, which would make used cars from Japan off limits, but dealers have put up a fierce fight. Finally in October the Motor Vehicle Import Supervisory Committee closed the last loophole – far too late, to be sure, but it was still a brave call and Minister for Commerce U Than Myint deserves applause for making it.

U Tun Tun, NLD lawmaker

For years, U Phone Maw Shwe ran Magway Region as his personal fiefdom, first as military commander and then chief minister. His word was law – as journalists, activists and anyone who got in his way would soon find out. So many were delighted when he was unceremoniously turfed from office in the 2015 redwash, with his USDP losing every single seat in the region. But if Phone Maw Shwe was hoping for a quiet retirement he was soon to be disappointed. Earlier this year, it was discovered that more than K7.5 billion in taxes collected from the region’s artisanal oil industry had gone missing on his watch. He has been forced to repay more than K3 billion and several vehicles to the regional government.

Many say he got off too lightly. But there’s a good chance nothing would have happened if U Tun Tun, the NLD lower house lawmaker for Pwintbyu, hadn’t campaigned hard on the issue from 2016. In a parliament that seems too often under the thumb of the autocratic NLD leadership, Tun Tun has shown that lawmakers can still play an important role in righting past wrongs.

U Tay Za, Htoo Group owner

We told you he was back! In October, U Tay Za graced our cover, as we detailed his recent moves to resume a more active role in Htoo Group, which had recently undergone a rebrand. What we didn’t realise was that he would soon be back in the headlines for all the wrong reasons. Soon the Kandawgyi Palace Hotel, the jewel in the Aureum Palace crown, was a smoking ruin. Two people were left dead and several injured, and guests were accusing hotel management of negligence due to the apparent failure of fire alarms and sprinkler systems.

To top it off, an oil refinery project in Dawei involving a Htoo affiliate was recently cancelled, and Asian Wings, which Tay Za reportedly owns through a proxy, was grounded in late November. It’s only meant to be temporary, but at the time of writing there was no sign of it heading back to the skies. With concerns about the banking sector growing, Tay Za will be hoping his bad run doesn’t continue into 2018.

bao_youxiang.jpg

Bao Youxiang, United Wa State Army leader

Myanmar’s beleaguered peace process was dealt yet another setback in April when seven non-signatories to the government’s Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement agreed to form a bloc, calling itself the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee.

The United Wa State Army, the country’s largest ethnic armed group, has taken a lead role in the FPNCC, hosting its first meeting at its headquarters in Panghsang, and in September UWSA chief Bao Youxiang was installed as its chairman.

The FPNCC and the military-government axis have differing viewpoints on the peace process regarding a number of issues. The FPNCC rejects outright the NCA and has called for a new path to peace to be forged, while the government insists on meeting with FPNCC members individually, rather than as a group.

As the Tatmadaw appears intent on ending the civil war through a show of military strength, a tactic that has not worked for the past 70 years, significant political manoeuvring will be required for any progress to be made on the peace process in 2018.

U Win Myat Aye, Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement

The former paediatrician was nominated as the Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement by the National League for Democracy when it came to power, and remained largely on the sidelines until the Rakhine violence erupted in late August.

U Win Myat Aye was among the first government officials to visit Maungdaw Township in the immediate aftermath of the August 25 attacks by fighters from the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, and he has played a prominent role in the government reaching a repatriation agreement with Bangladesh. The process is due to begin early next year, despite concerns from human rights groups that the situation in northern Rakhine is not conducive for the return of refugees.

In October, Win Myat Aye was nominated as vice chairman of the Union Enterprise for Humanitarian Assistance, Resettlement and Development in Rakhine, a public-private enterprise aimed at bringing humanitarian assistance and development to the restive state.

thaung_tun.jpg

U Thaung Tun, Minister for Office of the Union Government

In January, U Thaung Tun was announced as the country’s national security adviser. A career diplomat, he had previously served in roles in the country’s foreign service in Brussels, Geneva, Manila, New York and Washington when the country was under military rule, before his retirement in 2010.

His role as security adviser was to instruct the government on internal and external threats “by assessing situations from a strategic point of view,” according to an announcement by the President’s Office at the time of his appointment.

In an address to the UN Security Council in late September, Thaung Tun dismissed reports of human rights abuses by security forces in Rakhine State as terrorist propaganda and said they were nothing more than “malicious and unsubstantiated chatter”.

In November, the government announced that Thaung Tun would remain in his current position as security adviser, but also take on the role of Minister for the Office of the Union Government, one of two new ministries established by the government aimed at easing the administration’s workload.

Ko Michael Kyaw Myint, political prisoner

Until June 1, the name Michael Kyaw Myint meant little to most people. That evening, he sent invitations to journalists promising that at a press conference the following day he would blow the lid on corruption in the regional government, including chief minister U Phyo Min Thein’s office. Few believed he would follow through, but he did – despite harassment and pressure from local officials that forced him to shift venue.

Within 24 hours he was arrested and facing five charges, including online defamation, staging an illegal protest and being a “habitual offender”. He would spend more than two months in prison before being bailed in August. The following month he told Frontier that he could be “put in jail at any time”. They were prophetic words: in September he was arrested again, for sedition, ahead of a planned protest against the regional government.

Michael Kyaw Myint is hardly an anti-corruption crusader. He freely admits that he paid money to a Phyo Min Thein associate for his help to secure land in North Dagon Township. But the government’s response – to repeatedly prosecute him in an effort to force his silence – has turned him into something of a martyr. As Myanmar’s political realities have been upended by the tumultuous events of recent years, so have its heroes. Michael Kyaw Myint is the perfectly imperfect icon of justice for these strange times.

U Aye Ne Win and Ma Shwe Eain Si, nationalist power couple

True love or marriage of (political) convenience? Few pairings got tongues wagging in 2017 as much as U Aye Ne Win, the grandson of dictator Ne Win, and beauty queen Shwe Eain Si. Of course, there’s the age difference – Aye Ne Win is 41, Shwe Eain Si just 19 – but that’s the least interesting aspect of their partnership, which has a distinctly nationalistic flavour.

While his brother has been cutting deals with the Yangon government to import buses, Aye Ne Win has spent much of his time socialising and supporting the nationalist movement, encouraging protests against the government and meeting figures such as U Wirathu. He also likes to court controversy: in October, he attended Shwe Eain Si’s Halloween birthday party dressed as the pope. Although Aye Ne Win seems to pride himself on his good taste – he regularly gets around in a cravat and in 2016 upbraided Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on Facebook for serving Lipton tea at a state function – to many his behaviour is proof of the opposite.

Given their contrasting physiques, the relationship with Shwe Eain Si appears to be more a meeting of minds. In October, she became a household name when she was dethroned from a beauty pageant for posting a video “explaining” the Rakhine crisis, complete with conspiracy theories and images of mutilated bodies. Later that month she appeared at a pro-military rally in downtown Yangon, delivering a fiery speech to the baying masses.

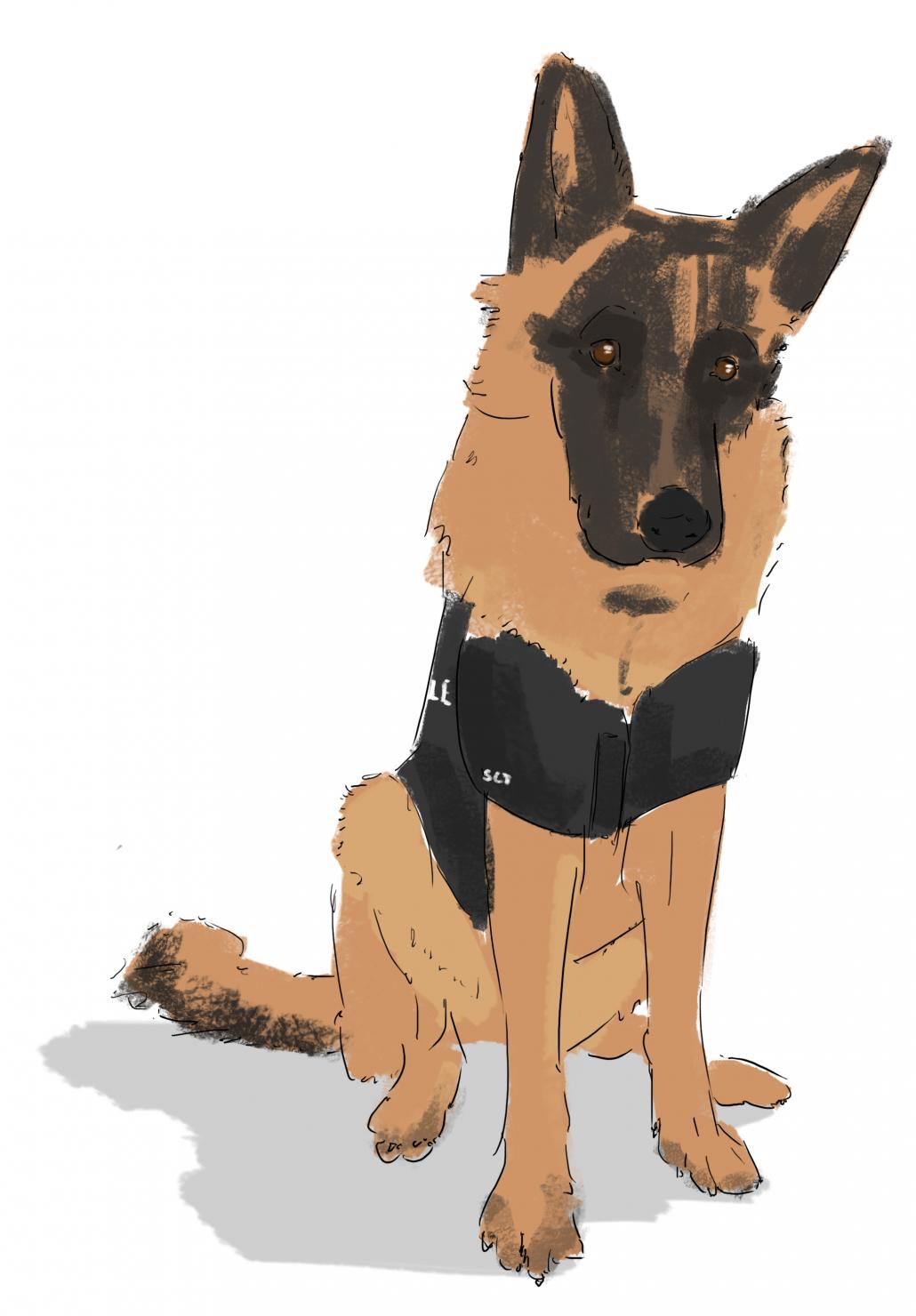

sgt_michael.jpg

Sergeant Michael, beloved canine

Few would have predicted the outpouring of grief that followed news of the death of police bomb squad dog Sergeant Michael on April 15, in the middle of the water festival holiday. Michael, who died from a stomach ailment, had clearly touched the lives of many with his always-friendly demeanour and commitment to service (he was Yangon’s only in-service sniffer dog when he died).

Michael’s death drew attention to the inadequate rations that the country’s small crew of sniffer dogs receive from the state, and prompted dog-lovers to form a non-profit group, For Brave Dog, to help provide better care. After learning that Michael had been buried in a nondescript grave next to a creek in Yangon, they also paid for a tomb – complete with Myanmar Police Force logo – out at Thanlyin’s pet cemetery. On May 15, the tomb was unveiled and Michael was honoured with a few minutes’ silence that, Frontier’s correspondent noted at the time, was “broken only by the barking of stray dogs”. While Michael has since been replaced by Rambo, his memory – and legacy – lives on.

daw_nan_khin_myint.jpg

Nang Khin Htwe Myint, Kayin State Chief Minister

It takes a brave leader to promote an unpopular project, but Nang Khin Htwe Myint has done precisely that. These days, coal power is a tough sell. But she’s announced that a 1,280-megawatt coal plant will be built in Hpa-an Township. When complete in 2023, it would almost certainly be the biggest plant of its kind in the country.

Perhaps brave isn’t the word: crazy brave might be more appropriate. Most political leaders would seek to distance themselves from the project, palming off responsibility to the developer (in this case Toyo Thai) or their underlings. She’s done precisely the opposite, campaigning for the plant at every opportunity and personally meeting with affected communities. Arguably, she’s staked her reputation on the coal plant and it’s still not clear whether that’s a wise move: Aside from the unpopularity of coal, some question the plant’s viability given the need to truck in about 11,000 tonnes of coal a day.

Khin Htwe Myint’s confidence reflects her elite standing within the party, as a central executive committee member. Since the resignation of Mon State Chief Minister U Min Min Oo in February, Khin Htwe Myint has also wielded increasing influence across the state border, regularly dispensing advice to Min Min Oo’s replacement, Dr Aye Zan.

U Win Khaing, Minister for Construction, Electricity and Energy

It’s fair to say that most members of the NLD cabinet have not exactly covered themselves in glory. But if Frontier had to name one who seemed to be getting down to business, it would be Win Khaing. He initially caught Aung San Suu Kyi’s eye as construction minister but in August was also given responsibility for the hugely important electricity and energy portfolio, in the first major change since the government was formed. Many breathed a sigh of relief when his predecessor, former Tatmadaw officer U Pe Zin Tun, left the building.

The review of Win Khaing’s performance leading the electricity and energy ministry is mixed: while there have been lots of positive indications, there is also still little to show on the key issues in the energy sector, such as tariff reform and the long-mooted liquefied natural gas contract. A big question for 2018 is whether Win Khaing can continue to lead two very important ministries – as the peace process stalls, delivering better roads and power have become the new objective for the NLD. It seems likely that he’ll give up one portfolio, but it’s still unclear which. Whoever takes energy and electricity will have some big decisions to make.

fmv3i16_white_rider_graphic.png

DISHONOURABLE MENTION: White Rider, foreign outlaw

In November our columnist called out the moped-riding foreigner known as the White Rider, who continues to defy the city ordinance against motorcycles. Some readers rose up in support of the White Rider, others derided him as a scofflaw, and Coconuts Yangon published a response urging authorities to spare riders of e-bikes (which are technically legal) as they hunt for the suspect. At the time of writing, the identity of the White Rider remains unknown, and sightings of his 125cc Chinese scooter continue.