Most of the nation’s children are educated at government schools, which are facing some significant challenges over a range of issues.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

WHEN THE rainy season arrives every June, parents and children begin preparing for the start of a new school year. Except for a small minority of children who attend private or international schools in Yangon, Mandalay or Nay Pyi Taw, most youngsters are educated in the government system. Here’s the basics of how it works:

Admission

Admission to government schools is simple and cheap. Lunch is not provided so students have to bring a gyaint (tiffin carrier). Most schools have snack bars, many of which were run by teachers until the 2005-2006 academic year, when the government ordered them to stop. Since then outsiders have been permitted to operate snack bars at schools. In Yangon, it’s common to see food stalls – many of them selling deep-fried snacks – outside school gates.

Some government schools are better than others and parents keen to ensure their children have the best possible education will not hesitate paying a bribe to secure admission to the school of their choice. This often happens when parents want their children to attend a school outside the township where they live, such as the highly-regarded former Christian-run schools that were nationalised after General Ne Win seized power in 1962. It is understood that parents can secure admission to such schools by paying a “donation” ranging from K100,000 to K1 million.

The corruption of the system is condemned by U Soe Win Oo, a private tutor, education reform campaigner and vice chairman of the National League for Democracy in Yangon Region.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“It’s a depressing situation when education has become a market from which some principals benefit at admission times; the government should do more to control this,” said Soe Win Oo, who has provided tuition for about 30 years under the name Dr Bio.

Corporal punishment

The use of corporal punishment appears to have declined slightly, but many former students speak of receiving beatings from kindergarten to high school.

Teachers hit students for many reasons, such as not paying attention, causing disruptions in class, falling asleep or failing to achieve high marks in tests. For example, in a test marked out of 10, students are expected to score at least seven. A student who gets low marks is like to be hit on their back, legs or palm of their hand with a cane or bamboo sticks that many teachers keep on their desks. Teachers who have big classes often believe they need to hit students to maintain control.

Education experts say corporal punishment can be eliminated if teaching methods are reformed. They say more awareness is needed to address the issue in Myanmar, where culturally and traditionally, beating is considered to be an effective way of dealing with rowdy students.

The role of parents

Each government school has an association of parents and teachers, similar to those in many other countries. A key difference in Myanmar is the way the associations are run. Parents cannot make suggestions and or raise concerns at the annual meetings of the associations. They have to sit and listen to what the teachers say.

Because of the importance of education to their children’s lives, many parents would like to play a more active role in the associations and are dissatisfied that they have to follow decisions made by teachers. Many parents are pushing for the government to reform the associations so they can have a greater say.

The curriculum

Discussions about the education system in Myanmar often tend to be dominated by the curriculum. Education specialists agree that the curriculum is badly in need of reform and would also benefit from the introduction of modern teaching methods and technology.

Some private school teachers said they would like to see some of the subjects taught in Myanmar schools updated.

Students at a mathematics tuition class in Yangon. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

“I think the topics in the textbooks of the current curriculum are quite old, and don’t really fit with the modern days,” said one private school teacher in Yangon. “This needs to be reviewed.”

Any revision of the curriculum would require careful consideration about subject content, including what languages would be taught.

The curriculum for primary students should incorporate classes in morality, and any such teaching should be secular and not religion-based. There are Buddha images and Buddhist shrines in every government school. Every morning after the assembly to sing the national anthem, the Buddhist students recite a prayer and teachers tell students of other faiths to be still and say their prayers in silence.

Any reform of the government school curriculum will be of little value if it cannot be taught effectively and more attention needs to be paid to teacher training.

Another issue affecting teachers is their pay and consideration must be given to providing a decent income.

Mother-tongue teaching

It should be no surprise that in a nation with 135 officially-recognised ethnic nationalities and eight main ethnic groups, mother-tongue teaching has been emerging as an important education issue and one linked to the peace process. A policy paper issued last month by the Ethnic Nationalities Affairs Center discusses mother-tongue based multilingual education.

The paper notes that teaching children in their mother-tongue is globally recognised as the most effective way for early learning to occur. Mother-tongue teaching is also mentioned in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities. Article 4.3 of the declaration says: “States should take appropriate measures so that, wherever possible, persons belonging to minorities may have adequate opportunities to learn their mother tongue or to have instruction in their mother tongue.”

The Naga Self-Administered Zone in the far north of Sagaing Region on the border with India provides examples of the disadvantages of using Burmese as the only medium of instruction. Most of the teachers in the zone are from lower Myanmar and because they are teaching in Burmese, the Naga children do not understand what they are saying.

“They also teach the kids the history of Bamar dynasties and kings, but it can be difficult for them to understand the terms used by the ancient Bamar kingdoms, and most students can only try to imagine the meaning of these words by closing their eyes,” said Ko Nok Tun, chairman of the Naga Cultural and Literary Committee in the zone’s Namyun Township.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

The teaching of history is a controversial issue in Myanmar and many in ethnic areas believe they should be taught the history of their own people as well as that of the Bamar.

Ma Nang K Thwe believes that more needs to be done to teach the history of the country’s ethnic minorities in public schools.

“We can look at the language issue from a human rights perspectives, or we can look at the language issue and the history issue from a transitional justice perspective, if Myanmar is really willing to genuinely reform,” Nang K Thwe said, adding that there should be a comprehensive education sector review involving all stakeholders, including ethnic nationalities, the government, the Tatmadaw and the United Nations. She stressed the importance of the language issue in the peace process.

The curricula at government schools should encourage democratic values, morality, tolerance of diversity and Myanmar’s social and cultural heritage. Achieving these objectives would require a sharp increase in funding for education.

Matriculation and beyond

The importance that almost the entire population places on the final matriculation exam cannot be underestimated. The exam decides the future direction of a student’s life and career and if they do not pass they will not have another chance to qualify for admission to university.

There is no equivalent in Myanmar of the General Educational Development test (also known as the General Educational Diploma and General Equivalency Diploma) in the US, which allows students who did not complete high school to qualify for university admission.

Anyone wishing to attend university in Myanmar must pass the matriculation exam. There are no options, which is unfair to those who could not or did not finish high school and decide after working for a few years that they would like to further their education.

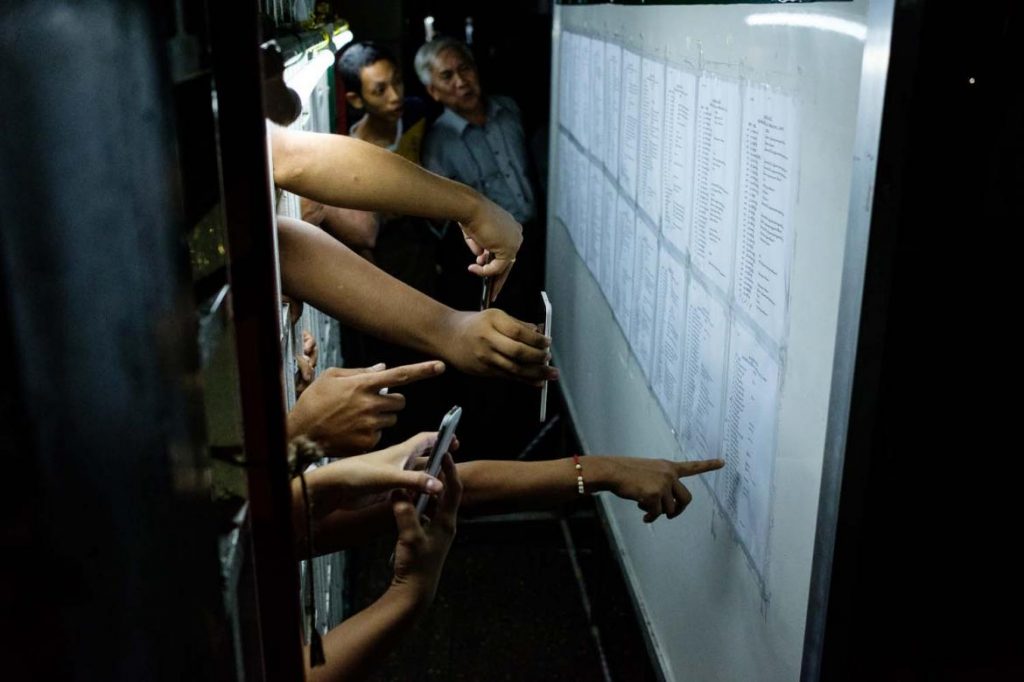

Students who pass their matriculation can face disappointment if they fail to gain admission to the university of their choice.

Critics of the matriculation system, also point to the fact that girls must gain higher grades than boys to study certain subjects at university. For example, in order to be accepted to study medicine, a girl must score at least 504, while a boy only needs to score 488. Other subjects where this applies include dental and nursing. The only subjects that boys need to score higher marks than girls are law and computer science.