A quick introduction to the past, present and future of Myanmar’s most important industry.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

Myanmar is a country of growers. The agricultural sector accounts for 37.8 percent of the country’s GDP, employs 70 percent of its labour force and generates 25 to 30 percent of total export earnings, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

Yet Myanmar falls far short of its agricultural potential. Its crop production per hectare is lower and it uses a smaller percentage of its arable land than almost all of its Southeast Asian neighbours.

Still, with output on the rise and modernisation efforts picking up, change is on the horizon – if not here already.

This is a quick guide to the state of Myanmar agriculture and its future potential.

Myanmar’s land

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

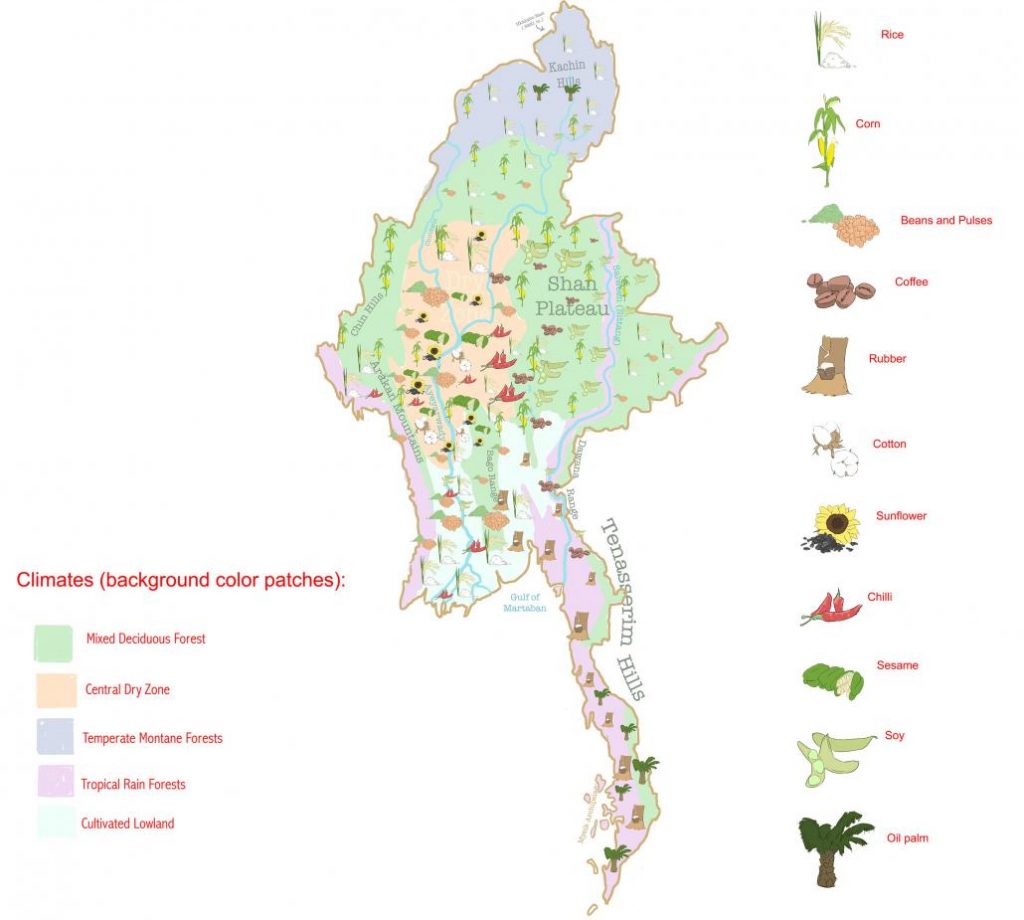

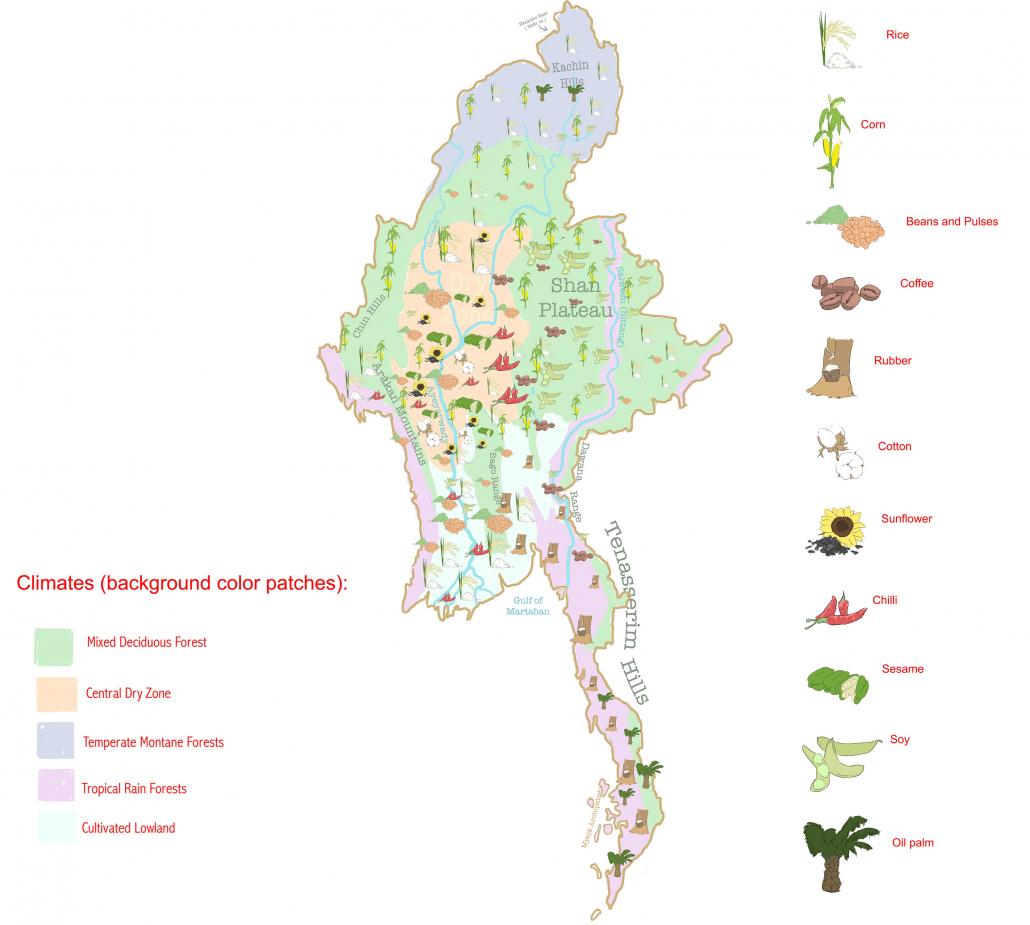

Myanmar has a huge land area and wide variety of growing conditions. It has more than 65 million hectares of terra firma, among the highest in Southeast Asia.

However, only about 20 percent of its land area (12.6 million hectares) is actually used for agriculture. To put this in perspective, Vietnam uses almost the same amount of land for agriculture despite being only half the size of Myanmar.

What Myanmar grows and when

The most common crops are rice, beans and pulses, and maize, in that order.

In general, farmers grow rice and maize during the monsoon season and beans and pulses during the dry season, although farmers in the temperate highlands often try for a second harvest of rice and maize if there is enough water left after the rains.

Likewise, in the water-rich Ayeyarwady Delta, farmers often eschew dry season beans for another paddy harvest.

Rice (including Myanmar’s most famous variety, paw san) and beans and pulses (especially chickpeas, green gram and black gram) are grown basically everywhere. Indeed, 80 percent of all Myanmar farmers grow rice and most plant beans and pulses after the paddy growing season, according to a survey published in 2016 by the World Bank Group.

That said, the rice production peaks around the Ayeyarwady Delta, while more beans and pulses (which can tolerate hotter, dryer conditions) are grown in the central dry zone.

Maize comes a distant third in terms of area cultivated. Unlike beans and rice, maize thrives in the temperate highlands, especially in Shan State, Sagaing Region and Chin State.

Myanmar produces a wide variety of other crops, though they boast nowhere near the production levels or export volumes of the top three.

In the arid soil of the central dry zone, farmers grow groundnut, sesame and sunflower, and fruits such as watermelons, oranges and chillies thrive in the hot days and cool nights.

In the Shan, Chin and Kachin mountains farmers plant soy, coffee, tea and strawberries, while onions, potatoes, pumpkins carrots and other vegetable are found in their temperate foothills. Rubber plantations are a mainstay of Kayin and Mon states, while Mon is also famous for its pomelo.

What Myanmar sells

Myanmar is famous for rice, and for good reason. Under British rule it became the world’s top rice exporter, thanks in part to the American Civil War (which levelled American rice exports) and the construction of the Suez Canal, both in the 1860s.

Myanmar may have long ago lost the title of top global exporter, but its people still holds the distinction of being the highest per capita consumers of rice in the world (at least according to the Myanmar Rice Federation). Not surprisingly, most rice is for domestic consumption: of the 12.2 million metric tonnes of rice produced in 2017, barely 10 percent – 1.4 million metric tonnes – was exported.

Although rice is by far the most commonly grown crop, the next in line, beans and pulses, steals the show for export revenue. Myanmar is second only to Canada in global exports of beans and pulses, exporting around US$1 billion of it in 2017, according to the Ministry of Commerce, versus only US$800 million in rice exports.

In 2017, Myanmar produced only 2.1 million metric tonnes of maize and exported 0.9 million metric tonnes, mostly as livestock feed, according to a 2017 report by the United States Department of Agriculture’s foreign agriculture service.

A quick introduction to the past, present and future of Myanmar’s most important industry. (Jared Downing | Frontier)

Myanmar farmers

Myanmar’s agricultural sector is largely comprised of smallholder farms between one and five hectares, according to Myanmar: Analysis of Farm Production Economics, a 2016 report by the World Bank Group that included a nationwide survey of farmers.

Although 80 percent of the 1,728 farmers surveyed cultivated rice, most of them also grew at least one other crop on their farms.

Mechanisation on these small farms is very low. Farmers rely on oxen and manual labour to plough, plant and harvest – in part because of the small areas they tend to cultivate.

“With regard to mechanisation, the good news is that in some areas of Myanmar, most farms operate only one parcel of land,” states the World Bank report, arguing that most of Myanmar’s farm plots are small enough to at least get by without sophisticated machinery.

Daily wages for farm workers range from roughly K2500 to K5500 – among the lowest in Asia – with wages at their peak during the dry season.

Sowing seeds for the future

Although the numbers have improved gradually in recent years, agriculture production and exports fall well short of Myanmar’s potential.

“[A]gricultural productivity in Myanmar is low … limiting the sector’s contribution to poverty reduction and shared prosperity,” the World Bank report states.

Dr Tin Htut Oo is a former director general for the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation and chairman of Yoma Strategic Holdings’ agriculture business. Regarding Myanmar’s agricultural growth, he identified three main blights.

First is its history: “A mistake policy-makers made in the past was to be too focused on rice alone. They failed to diversify,” Tin Htut Oo explained.

If Myanmar agriculture is going to develop, it needs to expand its exports of other crops. As an example, Tin Htut Oo cited coffee, which he argued has the potential to be as big an export for Myanmar as it is Vietnam, which is the world’s second-largest coffee exporter.

Second: Modernisation, but beyond mechanical ploughs and sophisticated fertilisers. Myanmar is woefully lacking in mills, canneries and other infrastructure to process its raw produce into marketable finished goods.

Finally: Market access and meeting global standards.

“The problem I would say in Myanmar is we are blessed with everything. We are satisfied with our own domestic consumption, so we do not need to import,” said Tin Htut Oo, arguing that Myanmar farmers tend to focus on selling within Myanmar.

Even if farmers had a network of overseas buyers, common practices for things like labour conditions and the types and amounts of fertilisers used makes many Myanmar crops ineligible for sale in global markets. He said a critical first step to upping Myanmar’s agricultural exports is for farmers to become aware of and then work to adopt international standards.