Tens of thousands of migrant workers in Thailand are anxiously waiting to return to Myanmar, where capacity to safely quarantine arrivals has transformed since the chaotic returns of March.

By HEIN THAR and BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

When State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi held a video conference with the chief ministers of Kayin and Mon states and Tanintharyi Region on May 5, one topic dominated the virtual meeting: the imminent return of tens of thousands more migrant workers from Thailand.

Reminded of the mass return of migrants in late March, which devolved into chaos and sparked panic, they took turns to repeat the same phrase: “Don’t let it be like the last time.”

Thailand hosts an estimated three to four million workers from Myanmar, who process seafood, sew garments and toil on construction sites across the country. When factories and other workplaces in Thailand began closing or shedding staff because of the coronavirus pandemic, tens of thousands faced a desperate future in the country. Unable to find other work or access state benefits, and with their savings disappearing on lodgings and utility bills, many decided to take the overland trip back to Myanmar, unsure of when they could return.

In late March, more than 40,000 migrant workers crossed into Myanmar via the border town of Myawaddy in Kayin State, across the Thaung Yin (or Moei) River from Thailand’s Mae Sot. The Myanmar government was seemingly unprepared for the sudden influx of migrants from a country with a higher reported incidence of COVID-19. Overcrowded waiting areas at the border gate descended into melee, migrants shared buses with other passengers headed to Yangon, and local authorities struggled to enforce orders for migrants to quarantine for two weeks at home once they were back in their towns and villages.

This fiasco prompted the Minister of Health and Sports Dr Myint Htwe to warn of the potential for a massive outbreak of COVID-19 in Myanmar, and migrants were widely scapegoated by the public as ill-disciplined disease carriers.

Though Thailand formally closed its borders on March 23, thousands of migrant workers were still able to cross in the following week. But at the start of April, the Myanmar government announced that all remaining migrants in Thailand who wished to return had to wait until April 15, and this was later extended to the end of the month. Thailand’s state of emergency, in effect since March 26, allowed the government to impose restrictions on movement, and many migrants who wished to return home were unable to reach the border anyway.

‘Some can’t survive for all of May’

As May approached, Myanmar began preparing for large-scale returns. On April 30, state media quoted the Myanmar labour attaché in Thailand as saying that 16,324 migrants had registered with the embassy to return, and that the group included 202 “illegal” migrants and 472 who were “without documents”. However, civil society activists who assist Myanmar migrants in Thailand estimated that tens of thousands more wanted to return, but had not filled out the online form. Activist Ko San Linn Aung, who liaises regularly with the embassy on behalf of migrants, told Frontier he believed the true figure was closer to 70,000.

But then Thailand decided to extend its state of emergency for another month, to the end of May. This preserved the restrictions on travel between provinces, for which medical certificates and permission letters are often required, as well as the suspension of the state highway bus network. For most, getting to the border remains impossible.

So the first two weeks of May passed with only a thin trickle of returnees. Myawaddy Distrct Administrator U Tayzar Aung told Frontier that by May 13, only 396 people had crossed the border. Of these, Tayzar Aung said that about 200 returnees who are mostly local to Myawaddy are now in quarantine centres in the border town, with the remainder having been sent to their home states or regions to quarantine there.

While Thailand’s restrictions persist, the large majority of migrants scattered across the country face an anxious wait. Ko Hla Wai Soe, who has been stuck in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai since work on construction sites dried up at the end of March, told Frontier on May 8, “We want to go back home so much, but the Thai government won’t allow us yet. Even their own citizens have difficulty going from one district to another.”

Migrant assistance organisations in Thailand told Frontier that they were focusing on providing food parcels to Myanmar migrants, many of whom have gone into debt just to pay for essentials. “People want to return to Myanmar to save money,” said Mr Johny Adhikari, founder of the Metta Charity, which works in Mae Sot and Chiang Mai. “They don’t want the pressure of paying rent and utilities while they’re out of work.”

U Htoo Chit, executive director of the Foundation for Education and Development, who lives in Phang Nga in southern Thailand, said he was getting calls around the clock from distressed Myanmar workers now out of a job. “Some can’t survive for all of May,” he said. “Others fear they can’t even survive for five more days.”

Reflecting the growing hardship, Myawaddy administrator Tayzar Aung said the number of migrants who had registered with the Myanmar embassy in Thailand to return had increased to 28,910 by May 13.

The embassy says it is negotiating with the Thai government to allow migrants to travel to the border at Mae Sot, and potentially other official crossings. In a May 14 announcement, it said it had requested Thai authorities to permit “2,500 or a suitable number of Myanmar workers to be able to travel to Myanmar border-gates daily” while the state of emergency is still in effect. The figure of 2,500 matches the capacity of Myanmar immigration and health authorities to admit and screen returnees at the No 2 Thai-Myanmar Friendship Bridge between Mae Sot and Myawaddy.

The announcement said the embassy had proposed that migrants also be allowed to exit Thailand at Ranong, opposite Kawthaung in southern Tanintharyi Region, and Mae Sai, opposite Tachileik in eastern Shan State, to make it easier for those in southern and northern Thailand. However, the Mae Sot crossing remains the focus, with the embassy requesting migrants be allowed to board buses at Bangkok for the border, preferably with an evening departure so they would arrive at Mae Sot in the morning.

However, the announcement did not say when the returns could happen, only that updates would given to migrants who had registered with the embassy.

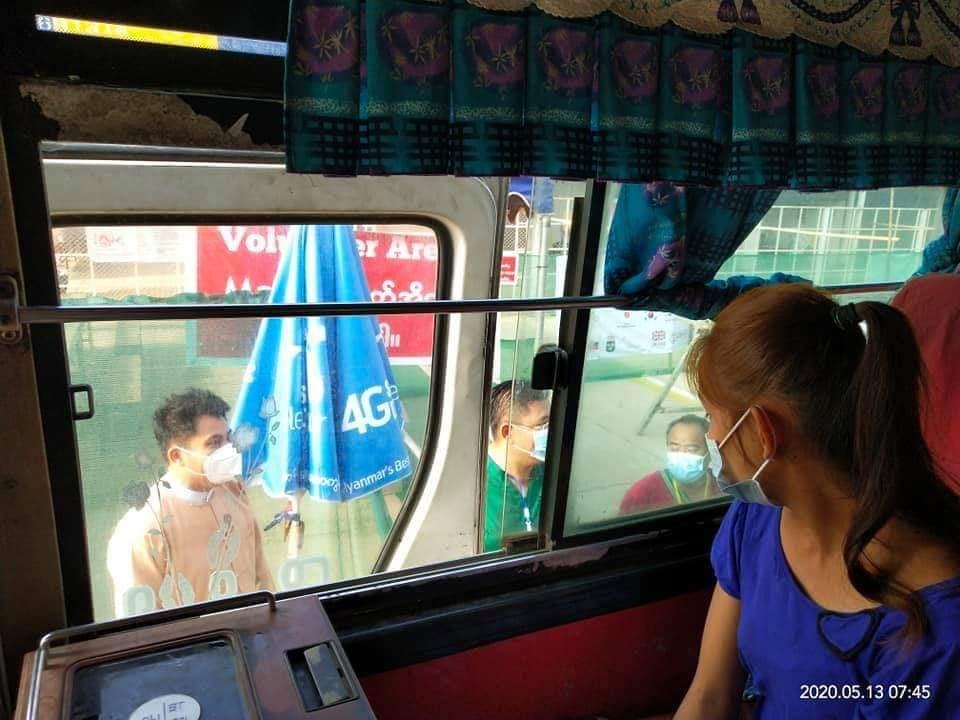

A returning migrant worker looks out from a bus at Myawaddy bound for Bago Region, where she will undergo 21 days’ quarantine, on May 13. (Supplied)

Quarantine centres multiply

Despite uncertainty over when migrants will be able to return and in what numbers, the infrastructure for receiving and quarantining returning migrants has been transformed since late March. At that time, a paucity of quarantine centres left the Myanmar government with little choice but to instruct migrant workers to quarantine at home. Many migrants disregarded or could not comply with this order, because they lived with extended families in homes where physical distancing is impossible.

During the May 5 video call with chief ministers, Aung San Suu Kyi stressed that home quarantine was now out of the question. While noting that “developed countries” allowed people to quarantine at home, she said this was “not practical in Myanmar” because of “local conditions”, a likely reference to more communal living arrangements.

Migrants returning to Myawaddy are now screened for COVID-19 symptoms at the border. Those suspected of having the disease are taken to Myawaddy District Hospital, while those who pass the screening are sent by the arrangement of the relevant state or regional government to the quarantine centre closest to their home town or village.

Since late March, community-based quarantine centres – often occupying schools, university halls and religious compounds that lay empty because of the pandemic – have multiplied across Myanmar. According to the health ministry’s latest situation report on COVID-19, dated May 15, there are now 10,122 such centres across Myanmar, hosting 59,539 people. Since April 11, there has been a mandatory 21-day quarantine period, up from 14 days previously, and this must be followed by seven days’ isolation at home. Ministry policy has limited admissions to quarantine centres to people arriving from abroad and those discovered via contact-tracing to have been exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients, but there have been reports of domestic travellers being forced into quarantine centres as well, particularly prior to guidance from state and regional governments forbidding the practice.

Kayin, Tanintharyi and Mon, which together form Myanmar’s southeast, account for the country’s highest rates of labour migration to Thailand, and so represent the frontline of any mass return. During the May 5 video call with Aung San Suu Kyi, Kayin State Chief Minister Nang Khin Htwe Myint and Tanintharyi Region Chief Minister Dr Myint Maung said their states both had the capacity to quarantine 5,000 people at one time, while Mon State Chief Minister Dr Aye Zan claimed his state had space for 7,000 people, and this could be expanded to 10,000.

Being locked for three weeks in converted schoolhouses with limited facilities during the hottest time of year represents an ordeal for many returning migrants. However, a yet-to-be published survey by the International Labour Organisation on the situation of returning migrants, some of whose results were shared with Frontier, found that many were happy to undergo this quarantine because it helped their reintegration, by reassuring communities who would otherwise be afraid that they were importing the virus.

Nonetheless, as reported previously by Frontier, local communities have to bear much of the burden of provisioning and staffing quarantine centres, and many have complained of a lack of government support. This burden will greatly increase if tens of thousands more migrant workers return, as anticipated. Ko Kyaw Thu Tun, a resident of Myawaddy who is volunteering for the township’s COVID-19 effort, told Frontier that “the government will not provide food for people in quarantine facilities; they have to rely on donors”.

Despite the strain, communities appear to have risen to the challenge. Frontier reported last month that the return of several thousand migrant workers from China via the border town of Lweje in Kachin State, starting on April 16, went smoothly thanks to the support of Kachin volunteers in ensuring that migrants were screened at the border and transported safely to quarantine centres in their home towns and villages, via transit centres in the state capital Myitkyina and Bhamo. The contrast with the March returns via Myawaddy was stark, suggesting valuable lessons had been learned.

Thousands wait to re-migrate

Kayin State lawmaker U Thant Zin Aung (National League for Democracy, Myawaddy-2) told Frontier on May 10 that future returns would be much better managed than in March, largely because of close coordination between the Thai and Myanmar governments made necessary by the travel restrictions in Thailand. “The Thai side will help a lot this time,” he said, including by preventing overcrowding in Mae Sot by migrants waiting to cross.

In March, migrants across Thailand individually boarded buses to Mae Sot, racing to reach the border before it closed. This led to crowds of thousands of anxious migrants at the No 2 Friendship Bridge, where Myanmar was accepting returnees. The need this time for Thai authorities to issue travel passes for migrants, who have had to register to return, allows numbers to be closely regulated – at least while Thailand’s state of emergency lasts.

But while these tight conditions allow for a more orderly process, it means tens of thousands of migrants face an uncertain wait with dwindling supplies of money and food. “I’m getting a phone call almost every hour from concerned migrants,” said Johny Adhikari of the Metta Charity, describing the frustration of being unable to tell them when they can return, and how.

However, the migrants who have returned to Myanmar since March and those waiting to return represent a small fraction of the Myanmar labour force in Thailand. Despite the hardship, the large majority are waiting out the economic shutdown in Thailand that has accompanied the pandemic. Many have invested considerable time, money and energy to legalise their immigration status and develop relationships with employers; some even run their own small businesses. Back in Myanmar, jobs are also scarce, and those that exist pay considerably less than in Thailand.

Even the mass returns in late March were far below the numbers usually seen in advance of the Myanmar traditional new year holiday of Thingyan in mid-April, when many migrants take the opportunity to visit their families in Myanmar for several weeks. Myawaddy administrator Tayzar Aung said this annual influx has in some years involved up to 300,000 people.

Many of those who did return before Thingyan this year wish to return to Thailand as soon as conditions allow. Half of the migrants surveyed by the ILO study said they wanted to re-migrate, mostly to go back to their previous jobs. Another 30 percent wanted to stay in Myanmar, with the rest saying they had no plans yet. Though the border remains closed to people crossing from Myanmar, the gradual lifting of restrictions on businesses in Thailand will heighten the demand for migrant labour, which forms a critical part of essential supply chains and industrial output in the country.

Some returned migrants say they only planned to visit Myanmar temporarily but were caught out by the new travel restrictions. Twenty-six-year-old Saw Samuel Aung, who is employed as a waiter at a seafood restaurant in Bangkok, said he only came home to renew his passport.

“When I arrived in Yangon [on March 15], the labour ministry told me I couldn’t go back to Thailand because of COVID-19,” Samuel Aung told Frontier. “So I went back to my hometown, Hpa-an [in Kayin State]. I’ve sought jobs here but the salaries are too low. My family depends on my income, so I hope I can go back to Thailand soon. My boss told me I can return to my job when the situation is more normal.” – Additional reporting by Ye Mon

Top photo: Returning migrant workers have their temperatures checked at the No 2 Thai-Myanmar Friendship Bridge in Myawaddy on March 23. (AFP)