Myanmar’s five million microfinance borrowers will resume repayments on May 15, but many are now jobless or on reduced incomes because of COVID-19 and the health of the US$1.3 billion sector is unclear.

By HEIN THAR | FRONTIER

Ko Zaw Zaw Aung, general manager at the Kyauk Sein footwear factory in Yangon’s South Dagon Industrial Zone, has been busy answering calls from employees wondering when they can return to work.

Like other workplaces around the country, Taiwanese-owned Kyauk Sein was unable to reopen after the 10-day Thingyan holiday in mid-April because of government COVID-19 prevention measures.

On the night of April 19, the government announced that all factories, workshops and offices would only be allowed to re-open after passing a Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population inspection.

Many of those calling Zaw Zaw Aung were worried about when they would be paid their April salary, he said, because they had looming repayment deadlines on loans taken from microfinance companies and non-bank financial institutions that offer credit.

Support independent journalism in Myanmar. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“Most of the workers have debts,” said Zaw Zaw Aung, who estimates that more than half of Kyauk Sein’s 1,300 workers owe money.

The factory eventually reopened on May 2, much to the relief of its workforce. Like the Kyauk Sein employees, many across the country have been eager to return to work in part due to pressure to repay loans.

“If I cannot repay my loan on time I will be in trouble with the company I borrowed the money from,” said Ma Win Lei Cho, a factory worker in Yangon’s western industrial suburb of Hlaing Tharyar, who borrowed K400,000 in February to pay rent and support her family back in Ayeyarwady Region. Since June 2019, microfinance lenders have been allowed to charge annual interest of up to 28 percent.

The pressure to repay debt can be stressful. Ko Yar Zar Kyaw Win, who works in a City Express convenience store in Yangon’s Kamaryut Township, said four of the six members in his family have borrowed money from microfinance lenders, and he has taken numerous loans out over the years.

“Without a job,” he told Frontier, “we won’t survive, because we won’t be able to pay our debts.”

Because of COVID-19, however, many workers have suddenly found themselves with reduced wages or even out of work completely. The government said in late April that 60,000 workers in the formal sector were now unemployed. The impact on the informal sector, which accounts for the vast majority of jobs, is less clear. But the shuttered restaurants, markets and construction sites around the country suggest steep job losses – and many of those affected will have debts to microfinance lenders.

In addition to 193 licensed microfinance institutions, Myanmar also has 29 non-bank financial institutions. Some of these NBFIs, like Mahar Bawga Finance, A1 Capital and Mother Finance, lend like an MFI but at a higher interest rate. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

A temporary reprieve

In an effort to reduce pressure on borrowers, the regulator for the microfinance sector, the Financial Regulatory Department, announced the suspension of lending and loan collections by microfinance companies from April 5 until the end of the month. This has since been extended to May 15. The directive said that neither principal nor interest shall be collected “by force”, although MFIs could still accept voluntary repayments.

Microfinance companies that confirmed to Frontier they were complying with the April 5 order include ASA Microfinance, Microfinance Delta International and MC Easy Microfinance. A staff member from one microfinance company told Frontier the firm had suspended operations but was preparing to resume collecting loans on May 15.

“We cannot collect by force; we can only collect from those who are able to pay,” said the staff member, who is based in Myawaddy Township, Kayin State.

Some microfinance lenders appear to have flouted the announcement. A follow-up announcement on April 14 warned that any companies found to be forcing borrowers to make repayments would risk having their operating licence withdrawn.

Although the announcement referred to companies violating the earlier order, FRD director general U Zaw Naing said no formal complaints had been lodged by clients who had been forced to make repayments during this period.

Many have also criticised the measure as being of limited benefit to borrowers. Given most companies will have collected March payments before the announcement, in practice it will only give most clients an extra two weeks to make their April payments, borrowers and companies told Frontier. Additionally, because it was not widely circulated, many borrowers had no idea they could defer payment at all. “I didn’t know about it until I saw it on Facebook in the second week of April,” said Ko Kaung Htet, a microfinance customer who works in a private bank. “By the time I found out, I’d already made my next repayment.”

“FRD should have known that this wouldn’t really be a helpful measure. Those who are really unable to repay should be given more time,” said U Myint Swe, director general of Microfinance Delta International, which has offices in all 14 states and regions and says it has issued thousands of loans.

Myint Swe said his company was surveying customers and would try to make it easier for those who cannot meet repayment commitments. Some may be eligible for emergency loans, he added.

“Microfinance companies should relax loan collection during the COVID-19 crisis and the government should announce specific instructions,” he said.

But Zaw Naing said FRD had no intention to extend the mandatory repayment delay further, and instead wanted clients who are unable to make repayments to “negotiate” with lenders.

The FRD order on April 5 also did not apply to the 29 non-bank financial institutions licensed by the Central Bank of Myanmar to provide credit, such as Excellent Fortune Finance, A1 Capital and Mother Finance. Some of these companies provide financing for specific purchases, including cars and even houses, but most are similar to microfinance lenders, issuing loans through the group borrowing system. The difference is they are allowed to charge interest of up to 36pc.

One such company is Yangon-based Mahar Bawga Finance, which says it has about 10,000 borrowers in Yangon.

After Mahar Bawga Finance was criticised on social media for continuing to collect repayments, it explained in a Facebook post that it operated under a licence issued by the Central Bank and did not need to suspend operations.

An assistant supervisor at Mahar Bawga confirmed to Frontier that the company was continuing to collect payments, but was also planning to negotiate with clients who were unable to make repayments because they had suddenly lost their job, been suspended without pay or had their salary reduced. Interest would still accrue on these debts during this period, he added.

But one client said the company – which some Facebook users have dubbed “Maha Lawba”, or Maha Greedy – was continuing to take a hard line on repayments. “I want to negotiate with them because I can’t pay but the company refuses to discuss the issue and are forcing me to repay,” said Ma Cho, who took a loan from the company in January.

Prior to the government enacting a law permitting microfinance businesses in 2011, most lending schemes were run by non-profits to give households in rural areas access to credit. (AFP)

The microfinance boom… and bust?

Many of the loans have been taken from microfinance companies that began operating in Myanmar after a Microfinance Law was enacted in November 2011.

Prior to the law being introduced, microfinance lending was limited to the state-owned Myanmar Agricultural Development Bank and some development projects, in particular a large programme run by the international NGO Pact. These covered a fraction of the population; in 2012, the United Nations estimated that unmet demand for microcredit was close to US$1 billion. When people needed money urgently, they often had no choice but to turn to illegal moneylenders, who typically charged interest rates of 10pc or 20pc a month.

Government data illustrates the boom in microfinance that has happened since. In 2012-13 there were 126 microfinance institutions, or MFIs, servicing 574,085 clients; three years later this had risen to 167 MFIs and 1,874,387 clients. Data from April shows there are 193 microfinance companies operating with the permission of the Microfinance Business Supervisory Committee of the Ministry of Planning, Finance and Industry, with more than 5 million clients (those who borrow from multiple MFIs are counted more than once). Most borrowers are from Yangon, Mandalay and Ayeyarwady regions, as well as Mon State.

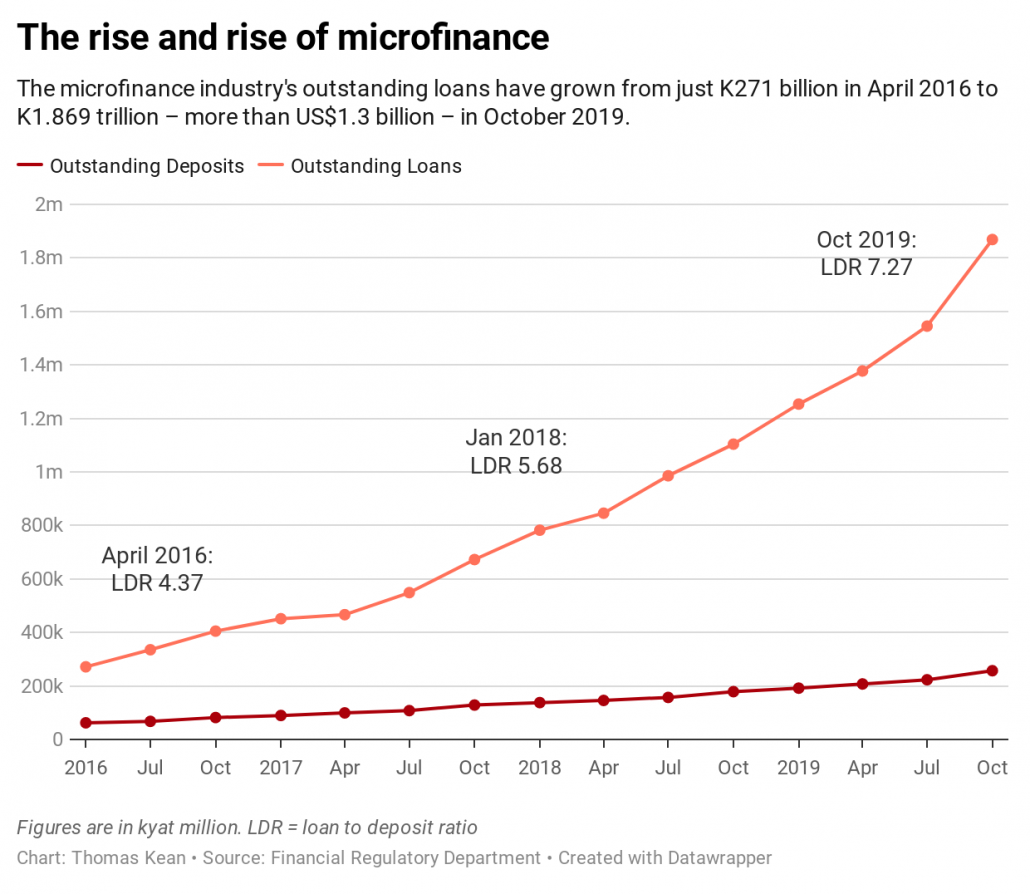

This growth has also been reflected in MFIs’ loan portfolios, which have expanded significantly since the government relaxed some restrictions on them in August 2016, including a rule that they serve as many clients in rural areas as urban. Data from the Financial Regulatory Department shows that at the end of September 2019 the microfinance loan pool was K1.87 trillion (about $1.33 billion), up from just K405 billion three years earlier when the rules were changed. Most loans are issued by a relatively small number of MFIs.

It’s not clear how many microfinance debtors are struggling to make repayments because of COVID-19’s effect on the economy. But even before the virus emerged in late 2019 there had been concerns about the health of the MFI sector and the social impacts of indebtedness.

Rates of non-performing loans do not necessarily provide a good indication. Many MFIs use a group lending system, where several borrowers’ debts are effectively combined into a single loan. When there’s a default, other members of the group are left to pick up the tab – but when they do, the loan is still considered repaid.

As the number of microfinance companies has increased, so have media reports about defaulting or absconding borrowers. Multiple borrowing has become increasingly common, as has reports of people taking on high-interest loans from informal moneylenders to repay debts to microfinance companies.

These concerns were borne out in a survey of more than 650 borrowers across 10 townships in five states and regions in June and July 2018. The survey found that almost one-third of respondents had three or more loans, and 25pc of respondents said they had difficulty making repayments. Multiple borrowing was more common in areas with a higher number of MFIs, like Yangon and Bago, and there was a strong correlation between the number of loans and the risk of payment default. Financial literacy training was mostly absent. The survey recommended limiting the number of MFIs in an area, conducting more checks on prospective clients and shifting from group to individual loans.

With many borrowers now likely out of work, the health of the microfinance sector has become an even greater concern. “This is a sector that has grown very rapidly over the past five years. There’s a lot of good to be said about that, but in the last year or 18 months or so, I’ve been hearing more about people cross borrowing and too many MFIs serving the same urban clients,” said one industry analyst. “This is always dangerous, but when there’s a real shock like COVID-19 the risks escalate … a lot of microbusinesses are going to be impacted because of COVID and that’s going to impact their ability to pay the money back.”

The Myanmar Microfinance Association – which represents 83 lenders, according to its website – is also concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on the industry.

General secretary Daw Phyu Yamin Myat said some microfinance providers, particularly in urban areas, had not been conducting proper checks on their customers before lending them money. She expressed concern that they may be too quick to issue emergency loans to borrowers who have no ability to repay. “There are some microfinance companies that are not working properly, that are just chasing profits,” she said. “The situation that always worries me is that in many wards there are so many microfinance lenders. It is difficult to track and know clients well.”

Phyu Yamin Myat, whose company MDP Microfinance has about 2,000 customers, said that lenders should continue to collect from clients who can afford to make repayments, and offer support, such as deferrals, to those who are unable to do so.

“That’s going to depend on the capacity of the microfinance lenders. They should know their clients’ situation: who cannot pay, who might be in trouble.”

But Zaw Naing from FRD insisted that COVID-19 would not create any problems for microfinance lenders. “Everything is still good,” he said, declining to provide further details.

typeof=

Emergency loans the answer?

If large numbers of clients are unable to pay back their loans, the damage will not be limited to the microfinance sector. A repayment crisis could potentially have flow-on effects on the country’s private banks, who are already grappling with their own bad debts. Many MFIs have borrowed from Myanmar’s private banks – which until March charged annual interest of 13pc, since cut to 10pc – to relend at higher interest rates to their clients. If clients fail to repay, they may default on their loans, further compounding the stress on the private banks.

“If MFIs can’t collect money, they’ll have problems with whoever is financing them, whether it’s banks or other institutions,” said U Hla Tun Oo, a manager at ASA Microfinance. “We will definitely start collecting debts again on May 15.”

In its COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan released on April 28, the government announced measures to ease the pressure on both banks and microfinance institutions. For MFIs it will try to ensure they have “full access to low-cost funding”, and instructs FRD to immediately oversee lending “as much as practicable” to the sector.

But there are concerns this could simply increase indebtedness. Several sources said that when new lending is permitted after May 15, some MFIs were planning to issue emergency loans to clients who are unable to make their repayment deadlines. It was unclear how they would assess the ability of these clients to repay the new loans.

“Most of the microfinance companies plan to issue emergency loans – for them, it is an opportunity to issue more loans,” said the MFI employee in Myawaddy.

“The more MFIs can give as loans, the more profit they make, so some of them issue loans very readily,” Myint Swe added.

The alternative, though, could be worse: some microfinance borrowers said that without emergency loans they may have no choice but to borrow from illegal moneylenders, who charge up to 20pc interest a month.

Ko Aung Myo Oo, 28, from Magway Township in Myanmar’s central Dry Zone, borrowed K800,000 from MC Easy Microfinance to buy a motorcycle. He had no problem making his repayments every month from the salary he earned working in a restaurant, but then COVID-19 hit and his employer was forced to close down. “I’m trying to find a way to pay back the money – I really don’t want to be late or default, because it will make it harder to get a loan next time,” Aung Myo Oo said. “Right now I’m thinking to take a loan from a moneylender in my ward.”

Others are hoping that their lender will give them more time.

Ma Zar Zar Wai Khine worked at the Brightberg Enterprise bag factory in Yangon’s Dagon Seikkan Township, which closed permanently on April 27. She missed her last payment, but said she had not yet been contacted by the microfinance company that lent her the money. Part of a loan group of 11, she said “at least two or three” others were also unable to make repayments.

The approach of May 15 fills her with dread, because she knows the company will call shortly afterwards to demand the next instalment.

“I think they’ll give me a bit of extra time, but they’ll definitely want to set an exact date for the next payment,” she said. “But how can I say when I’ll be able to begin paying the money back? I have no idea when I’ll be able to get another job. If possible, I want them just to delay it until I get a new job.”

But with its own debts to repay, her microfinance lender might not be so forgiving.