After decades in the doldrums, the nation’s movie industry is on the road to recovery and expansion, thanks partly to the contributions of young, foreign-trained film makers.

By SITHU AUNG MYINT | FRONTIER

IN EARLY December, the director of the film Now & Ever (htar wara hnaung gyo), and the main actor, actress and others involved in the successful movie held a meeting with their fans in Yangon.

The director, Daw Christina Kyi, revealed how much the movie earned at the box office and what taxes had to be paid.

She said it cost K700 million to produce the film and box-office earnings totalled K2.4 billion, which was split between the production company, Central Base Productions, and cinema owners.

The K1.1 billion for Central Base Productions, she said happily, meant that the screening of the movie earned the company three-and-a-half times what it cost to make the film.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The figure does not include earnings from screening the movie in foreign countries such as Singapore and when it is screened on television or distributed as a DVD.

Christina Kyi said Central Base Productions had to pay income tax of K110 million on Now & Ever, and K70 million on two earlier productions, for a total of K180 million.

The country’s movie industry is, at long last, showing signs of recovery.

However, Now & Ever is not the highest-earner at the box office. That distinction belongs to the movie known in English as “The tear drops shed on Yoma mountain range”, which cost K650 million to make and earned K3.5 billion at the box office.

The difference in box-office takings between the two films is because of the number of cinemas where they screened. Making money from movies often depends less on their quality than the availability of cinema screens. The more screens, the higher the take at the box office.

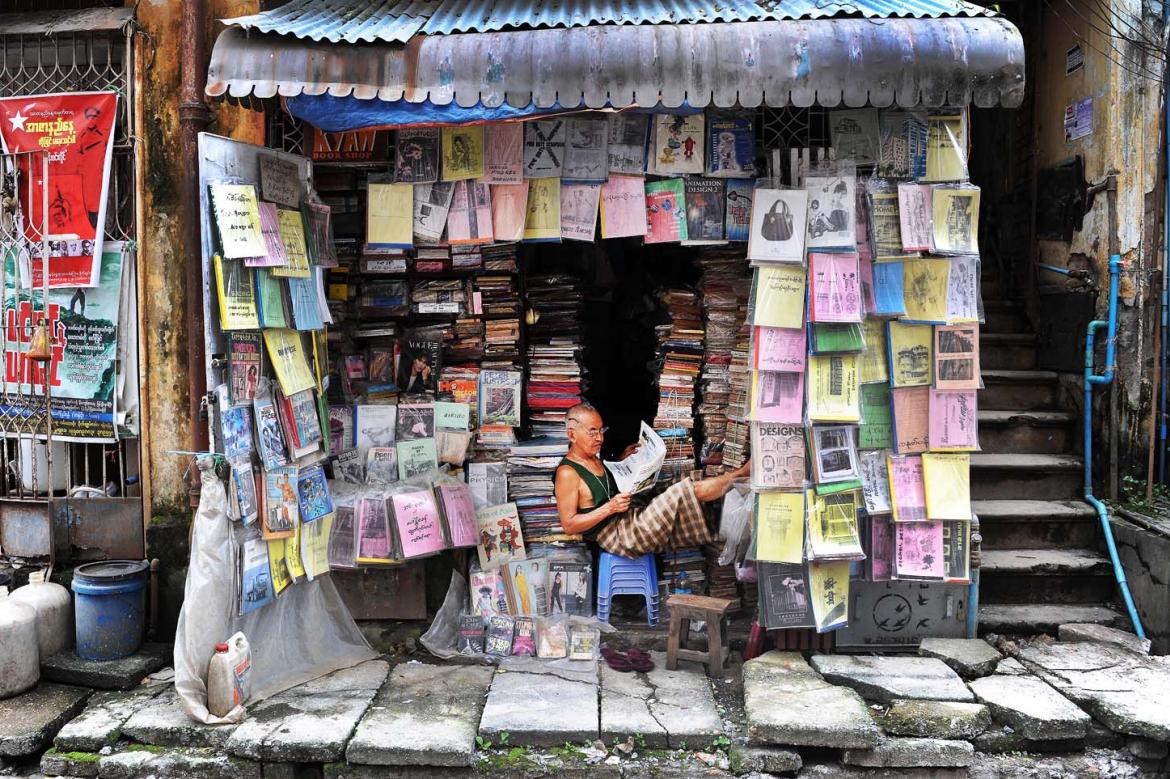

There were 421 cinemas throughout Burma until 1988, when the country was ruled by the Burma Socialist Programme Party led by the dictator, General Ne Win. Each cinema had one screen and all were state-owned. The military government that ruled the country after 1988 sold off the cinemas, ostensibly so they would be upgraded.

However, in most cases, the cinemas were used for other purposes. It was a pity that so many old cinemas were lost. In 2000, there were just 42 cinemas in the entire country, a fraction of the number 12 years earlier.

The situation in Myanmar differed from that in Vietnam and Cambodia, where the film industry was affected by the large number of cinemas destroyed by years of war. The film industry in Myanmar collapsed because of the mismanagement of successive military regimes and strict censorship, which contributed to a decline in movie quality.

Under the economic reforms introduced by the military regime that took power in 1988, businesspeople began investing in building cinemas. This led to the rise of Mingalar Cinemas as a dominant player in the industry. It had begun in the industry by leasing, renovating and operating cinemas from the government.

Other companies that invested in the cinema business included JCVG, Mega Ace, Red Radiance, Standalone and Paradiso. Many of the big shopping malls built in recent years have cinemas, increasing the number of venues available to movie fans.

There are nearly 200 screens throughout the country and the increase in the number of cinemas has corresponded with a rise in the number of producers keen to cash in on the prospect of popular productions.

More screens have accommodated a gradual rise in the number of movies. There were nine productions released in 2014, rising to 32 in 2015, 98 in 2016, 158 in 2017, 133 in 2018, and 94 to November this year.

The steady surge in production has created a challenge for the industry because it has resulted in a back-log of movies that have been approved by the censorship authorities but are waiting to be screened.

In 2016 there were 12 movies cleared by the censors that were waiting to be screened, rising to 18 in 2017, more than 40 in 2018 and in excess of 60 so far this year.

This has created a difficult situation and resulted in constant negotiations between cinema owners and film producers.

There is considerable potential to make a profit from a well-made film that audiences like, said director and veteran actor Maung Thura aka Zarganar.

He estimated the cost of producing a movie at between K350 million and K7.5 billion (about USD$230,000 to $4.9 million at current exchange rates), and said the biggest expense was the cost of actors. A famous male actor gets paid between K70 million and K90 million a film, and a starring female actor gets K50 million to K60 million, he said.

Zarganar said a blockbuster production could earn up to K3.5 billion but a production that was not greatly liked by movie-goers could realise as little as K40 million or K50 million. Sometimes a movie could incur a big loss, he said.

The powerful companies that have invested in building cinemas and the emergence of financially strong production companies have brought some positive changes to the industry. The fact that a big Chinese company is known to be exploring opportunities for building production studios – which would be a major investment – reflects the industry’s recent growth.

Movie-making has also changed as a result of the involvement of Myanmar people who have studied filmmaking abroad, such as Christina Kyi and her husband, the actor, scriptwriter and singer Zenn Kyi. They have both lived in New York, where Christina Kyi graduated in digital filmmaking and multimedia from Gibbs College, and Zenn Kyi graduated in music from the City College of New York and in film scoring from the Institute of Audio Research.

The movie industry has also been hiring actors from Thailand, South Korea and Japan and producing films in partnership with foreign companies for screening to domestic and overseas audiences. There has also been foreign investment in building cinemas.

After many years of decline and stagnation, and a few promising years of growth, the Myanmar motion picture industry now seems poised for major expansion, in which foreign investment is likely to play a role.