A grand plan to redevelop Yangon’s main railway station faces several obstacles – not least the resettlement of 10,000 Myanma Railways employees and family members – but has the potential to redefine the downtown area.

By HEIN KO SOE | FRONTIER

DURING RUSH hour in Yangon, the platforms, concourses and walkways around Yangon Railway Station are crammed with people heading to and from workplaces in and around downtown Yangon.

The busiest area is the walkway along the edge of the Pansodan Bridge, which spans the railway compound and links directly to the platforms below. Most Yangon residents – and many visitors from other parts of Myanmar and abroad – know this stretch of pavement well.

jtms-ygnrailw-16.jpg

A train carriage passes through Yangon Central Station. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Beside the bridge, however, is a community of thousands who live mostly out of site but are essential for keeping the trains running.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The small Mee Yahtar Yatkyet Ward is home to operational staff of state-run Myanma Railways.

The rooms here are tiny; whole families are crammed into dilapidated 100 square feet buildings that date to the colonial era. Many residents have taken adjoining land to build additional rooms, creating a chaotic and cramped atmosphere. The community is largely self-contained, featuring teashops, restaurants, groceries and small stores selling fresh produce.

jtms-ygnrailw-08.jpg

A passenger sits in the waiting area of Yangon Central Station. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Although the first railway station was built in the area in 1877 – when it was referred to as Kun Chan station – the present, heritage-listed station building dates to 1954.

Most of the staff housing is from the 1940s. Many residents have lived here for most or all of their lives.

Hoping for better

U Sein Nyunt, 78, has lived in Mee Yahtar Yakyet Ward since 1959, when he began working for Myanma Railways. He retired in 2000, but still lives in government housing because his son-in-law works at the railway station.

He also shares the house with his two daughters and two grandchildren. “It’s very difficult for us to live in this little space,” he said.

jtms-ygnrailw-22.jpg

U Sein Nyunt, 78, who has lived in Mee Yahtar Yatkyut Ward since 1959. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Ward administration office figures show that more than 4,300 people live in 528 households. But even administrator U Aung Myo Naing doesn’t believe these numbers; he estimates that more than 10,000 people call Mee Yahtar Yatkyet home.

Residents of Mee Yahtar Yatkyet are both anxious and hopeful about what the future holds. In 2014, Myanma Railways unveiled plans to redevelop the central railway station into a US$2.5-billion, mixed-use precinct, with improved public transport facilities and public space as well as retail, residential, serviced apartments and a hotel.

Residents said they had first heard of the plans about five years ago. Sein Nyunt hopes that when the family is relocated, they will have more spacious accommodation.

“If they want to resettle us they need to build the new housing before we can move,” he told Frontier, adding that he was aware that plans had been made for relocation.

A 70-year-old woman who declined to give her name said she was living in the compound because her son worked for MR.

“We don’t know when we need to move; but we don’t worry about it because now the government will do its best for us, I think,” she told Frontier.

jtms-ygnrailw-29.jpg

A street in Mee Yahtar Yatkyut Ward. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Myanma Railways Division 7 in-charge U Soe Moe Tun said none of the employees and their families living in the compound need worry about being relocated.

“We have a better plan for them,” he said, referring to residents of the crowded residential compound bordered by Pansodan and Kun Chan roads and U Phoe Kyar Budar Street.

Soe Moe Tun said the tender process and conceptual plan for the redevelopment provided for MR administrative staff to be resettled in Tarmwe Township, and maintenance and other workers to be relocated to Ywartharygi in East Dagon Township.

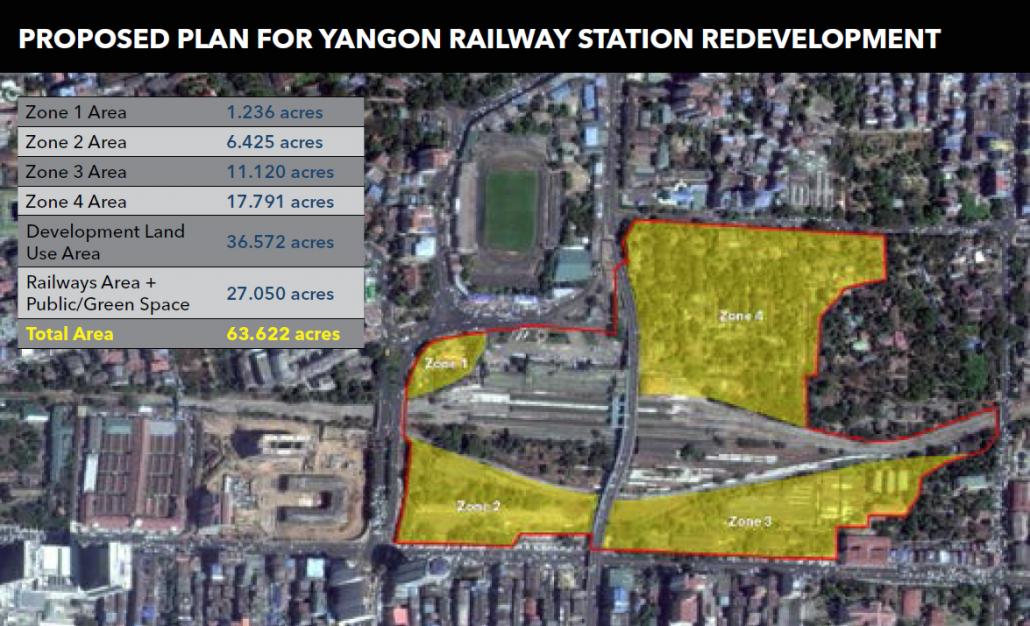

railway-redevelopment-map.jpg

More than a decade ago, Myanmar’s military rulers had proposed shifting the central railway station to the Ywarthargyi site, which is on the city’s outskirts and beside the Yangon-Mandalay line. The land will instead be used for staff housing and other facilities that will be built by the winner of the railway station redevelopment tender.

“We will build the apartments for our staff before the relocation begins,” Soe Moe Tun said.

jtms-ygnrailw-24.jpg

Myanma Railways Division 7 in-charge U Soe Moe Tun. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

A smooth relocation will be essential to eliminate the possibility of disruption to MR inter-city trains and the Yangon Circle Line, a vital service for tens of thousands of city residents.

Missing bidders

In May 2014, the previous government called for expressions of interest in redeveloping the prime site on the edge of the downtown area.

The winning tenderer will be permitted to build on 40 acres (about 16 hectares) of the 63.622-acre site. In addition to resettling Myanma Railways staff, the developer will be required to refurbish the station’s heritage buildings so that they retain their architectural integrity.

Aside from the size and location, another attraction for developers is that the site does not feature strict height limits.

jtms-ygnrailw-31.jpg

A young girl leans outside houses in Mee Yahtar Yatkyut Ward. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

While interest has been high, few companies have been willing to table formal bids. Myanma Railways initially received 34 expressions of interest from 12 different countries, and shortlisted 28 potential developers. However, the tender was cancelled after only three formal proposals were received by the January 6, 2015 deadline and none were deemed suitable.

The following August, Myanma Railways announced a new tender, once again calling for expressions of interest. In February 2016, it announced that 15 had been received from prospective developers or joint venture partners in 14 countries. Eight of

The second time around, though, just two formal proposals were accepted: one from a consortium including First Myanmar Investment and Singapore-based Yoma Strategic Holdings – both companies linked to Mr Serge Pun – and another headed by a local company, Min Dhamma, that reportedly includes partners from China and Singapore. Min Dhamma is a subsidiary of Mottama Holdings, a Yangon-based conglomerate established by Myanmar-Chinese.

jtms-ygnrailw-10.jpg

An engine driver looks out the window while passing through Yangon Central Station. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Soe Moe Tun said a third consortium had submitted a proposal but it was not accepted because it had been missing some documents. He declined to give the name of the rejected consortium.

He said the Ministry of Transport and Communication was finalising its evaluation of the proposals and the winning bidder would be announced following cabinet approval.

Although Myanmar Times recently quoted Myanma Railways general manager U Htun Aung Thin as saying the project would get underway next year, Soe Moe Tun said no date had been confirmed.

Tender design

Myanma Railways has blamed the lack of proposals on the requirement that consortiums pay a US$4 million bond. Despite acknowledging this was an issue after the first tender, it kept the requirement the second time around.

Frontier sought comment from a dozen shortlisted consortiums from the second tender, as well as several from the first. Most did not respond or declined to comment. Yoma Strategic said it could not comment because of a confidentiality clause in the bidding documents, while Mottama initially said it would answer questions but did not do so by deadline.

jtms-ygnrailw-11.jpg

Commuters walk along the platform at Yangon Central Station. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Several sources said a range of factors had discouraged proposals, particularly the size and projected cost of the project. Myanma Railways had made clear early on the developer would need to take on the entire project, rather than it being split into sections. Another issue was the resettlement of Myanma Railways staff, the cost of which would have to be borne by the developer.

A representative from M&A-Iconic Group, a company associated with U Moe Myint of Myint & Associates, said it decided not to pursue its interest in the project because there was not enough time to undertake a full technical feasibility study. The company unsuccessfully sought an extension to the proposal deadline.

“For example, soil analysis became a critical requirement before committing – if the soil was too soft, as apparent in quite a few other projects in Yangon, that could easily increase the capital expenditure by another 50 percent,” the representative told Frontier.

U Tint Swe, a general manager at Excellent Fortune Development Group, said his company’s consortium missed the deadline by about five minutes.

“The other bidders objected so Myanma Railways did not accept our proposal,” he said.

Frontier was unable to independently confirm this account.

jtms-ygnrailw-35.jpg

A Myanma Railways employee stands in a train carriage. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Mr Tony Picon, the vice chairman at real estate consulting firm Colliers International Myanmar, said Myanma Railways could have encouraged more bids by commissioning some of the preparatory studies itself and then making the results available to all who bought the tender documents.

He said he wasn’t surprised that so few companies decided to submit a formal proposal.

“It’s very easy to submit an expression of interest,” he said. “But when you get to the next stage, there’s a serious amount of time, money and resources that go into the bidding. This is not just a three-page document with pretty pictures.

“When consortiums think there will be at least three or four other bidders, are they going to spend all that money? I think most bidders will baulk at that and that’s the problem … and it’s not just [the financial cost of bidding], it’s also resources.

“You’ve got a Catch-22 where you want the private sector to do all the work but the private sector needs some strong guarantee that they’ve got a chance [of being selected] if they do all that work.”

A spokesperson from another company that took part in the EOI process said that for such a large and prominent project – phase one alone would likely have required US$500 million in investment – a public-private partnership with more state involvement would have been a better model instead of a tender.

Downtown dominance

Despite talk over the past five years of the city’s CBD shifting up to Inya Lake, the opposite has in fact happened. The development of Junction City and Sule Square has resulted in the commercial heart of Yangon gravitating south back towards the river. Yoma Central (formerly known as Landmark) will only reinforce that trend further.

While those projects are large by Yangon standards, they are still small compared to the proposed central railway redevelopment. The site’s size and location make it a “game-changer” to the downtown area, Picon says.

“There are other large land plots but not right in the centre. It’s pretty unusual for a city to have that sort of land available,” he said.

But the public transport element also makes it unique. The redevelopment fits into planned upgrades of the Yangon-Mandalay and Yangon City Circle train lines, while conceptual documents released by Myanma Railways suggest it may also include bus and taxi stations.

jtms-ygnrailw-05.jpg

Train carriages sit in the sidings of Yangon Central Station. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Picon said the site’s project role as a transport hub could be both a negative and positive for developers.

“The success of the railway development … will have a major impact on the [property] development. The two are intertwined. You add on a mass transit line and station, and that enhances the property around it.

“The project could work anyway. But with a good railway system you’ll get, for example, middle-class people from the outskirts commuting to work and that will bring retail customers.

“The worry I have is that you have a beautiful new terminal and you have clunky old locomotives coming in rather than high-speed trains.”