A contentious vote in the northern Shan State capital in 2015 is a cautionary tale for election officials committed to making this year’s election free, fair and transparent.

By YE MON | FRONTIER

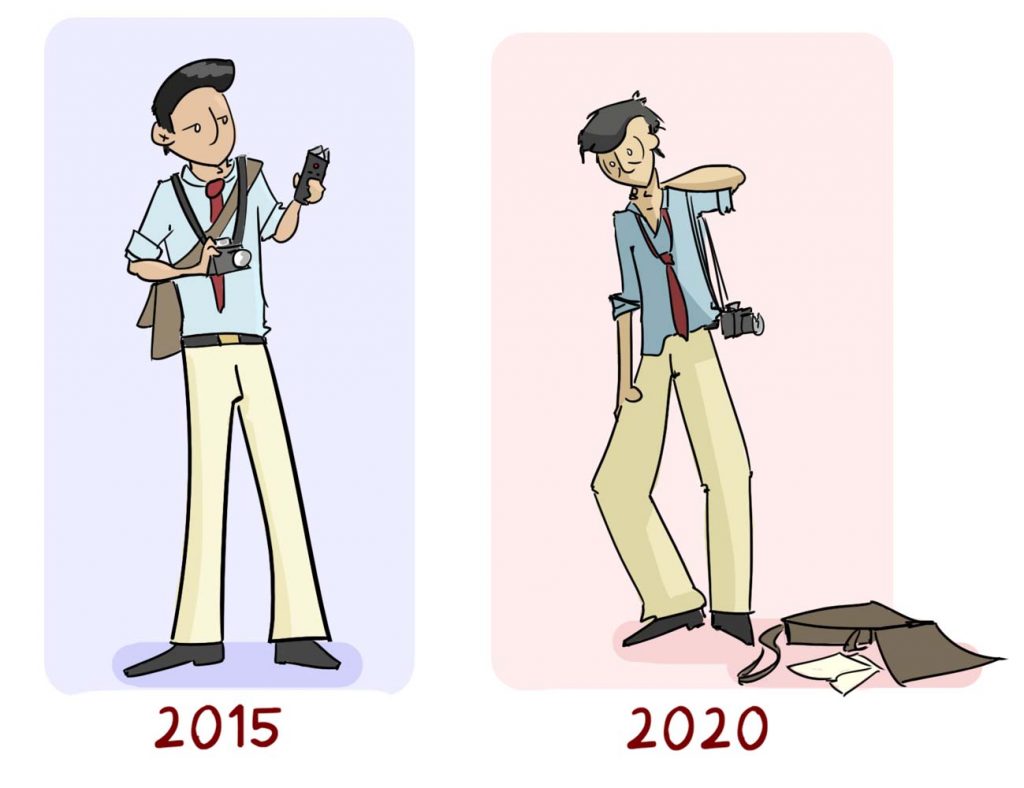

Myanmar was buzzing with anticipation ahead of the 2015 general election. Finally, the time had come for a fair and free vote whose result would reflect the will of the people.

The coming election on November 8 lacks the zeal and historical shine of 2015, and though it is certainly important for our democracy, the prospect of change is not so strong. Frankly, I am not as excited to cover this one.

As a reporter covering one of the most intriguing votes in Shan State, the 2015 election was fun but often stressful. I had been assigned to Lashio for five days to report on the heated battle between three frontrunners, the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party, the National League for Democracy and the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy.

The USDP candidate for the Pyithu Hluttaw seat was the incumbent Sai Mauk Hkam, then also the country’s vice president. He was pitted against the NLD’s U Tun Shwe, who appeared to be striding to victory after attracting most of the regular votes.

Then thousands of advance votes arrived at the township election sub-commission after the 4pm cut-off time, according to the NLD and SNLD, which wrote a joint letter of complaint to the sub-commission after nearly all of the advance votes favoured the USDP.

The parties argued that the out-of-constituency advance votes – most of which were ostensibly cast by soldiers serving away from cantonments in the township, with no transparency – should be cancelled because they were delivered late. They also questioned whether the soldiers had really all voted freely for the USDP.

In the end, thanks to advance votes, Mauk Hkam defeated Tun Shwe by 30,909 votes to 26,726 – a result the UEC took three days to confirm.

Invest in Frontier Myanmar’s independent journalism by becoming a member. Sign up here.

But advance voters weren’t the only problem in the electoral battle for Lashio Township.

Election officials stopped media from entering some polling stations despite reporters presenting official accreditation cards. Perhaps the rejection was because of a misunderstanding of the commission’s media guidelines, but it stopped reporters from providing a more complete picture of voting and counting.

We were also barred from entering polling stations in military compounds, even though these were open to people bearing accreditation cards elsewhere in Myanmar. The recent decision to move polling stations outside of cantonments should mean that observers and media can observe military voting on election day more freely this year.

Another change will hopefully come for photojournalists, who have previously been barred from taking photographs of polling stations. Asked about the restriction at a meeting with parties in Yangon on June 27, UEC spokesperson U Myint Naing said the commission would reconsider it. However, based on the number of polling station photographs in 2015, the ban was clearly not always enforced.

Although these moves are encouraging, the COVID-19 pandemic might provide electoral authorities with an excuse to restrict access again. I only hope that the UEC will see media freedom as a crucial part of a free and fair election. We’re only trying to do our jobs.

There was one more lesson I took away from that election in Lashio. Dr Lin Htut, a Bamar dentist originally from Ayeyarwady Region, was vying for one of the state assembly seats. In the run-up and just after the election, Lin Htut was friendly with reporters and easy to contact, but that changed when he was then made chief minister of Shan – an appointment that disappointed Shan parties who had expected the NLD to pick a Shan candidate.

After his appointment, he became much more difficult to reach, but he was not the only one; other MPs were just as amiable and accessible with reporters around the election – perhaps because they thought it would boost their image – but that quickly changed when they became ministers.

With another general election looming, ministers are suddenly answering the phone to reporters again. But whether they will give us direct answers is another question – unfortunately there’s not much the UEC can do about that.