Foul-mouthed rockstar Kyar Pauk used to wrangle with censors for artistic freedom, now he won’t take orders from anyone — not even his fans.

By JOSHUA CARROLL | FRONTIER

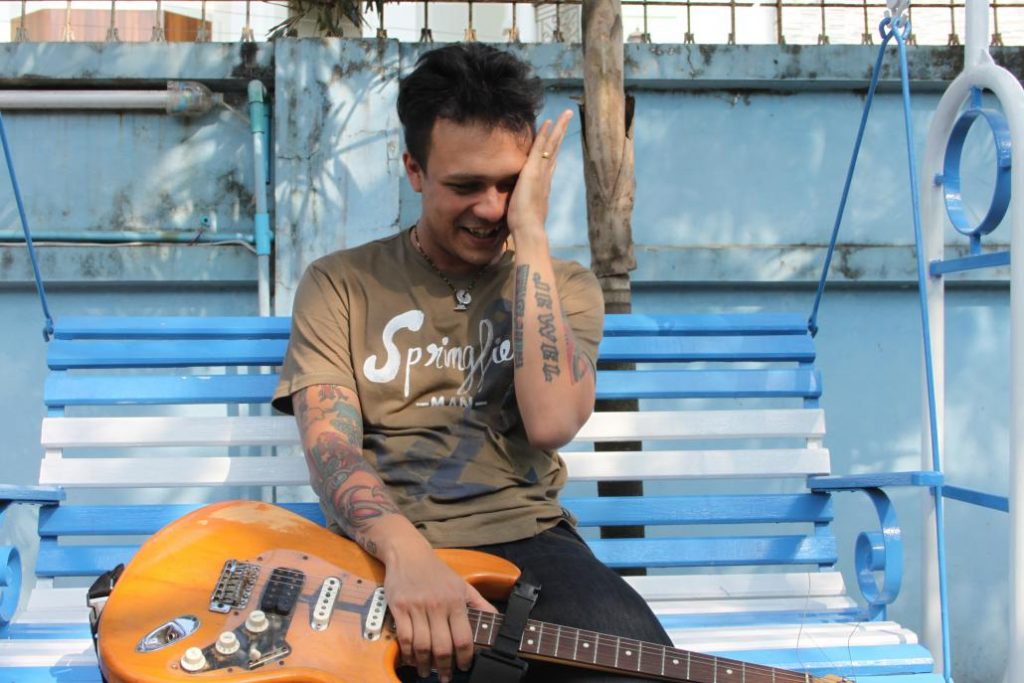

As he swigs beer in the front yard of his Yangon home, Kyar Pauk looks like a quintessential rebellious rock star. He is sarcastic, always grinning, with tattoo-covered arms and an expletive-ridden vocabulary. But don’t, he insists, assume his jovial disregard for authority is politically motivated.

“Most people think I have this kind of activist mentality or something,” he says, his eyes creasing as he smiles. “But I don’t. I just don’t care. I’m just here to witness what people are doing and just laugh. I’m here to make jokes.”

After spending the best part of 12 years battling a stuffy censorship board, which routinely banned songs by his three-piece band Big Bag and demanded he change certain lyrics, the frontman and guitarist could find plenty of reasons to rage against the system. But he prefers to see its funny side.

Far from being bitter about the days before official censorship was lifted in 2012, he has fond memories of his wrangles with the men holding the red pens. “I like pissing people off,” he says. “The obstacles were there, censorship was watching and I wanted to find a way to get around that, that’s my pleasure.”

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

One of his favourite methods for dodging the military junta’s draconian restrictions was the “bleeping system”. “I bleeped myself when I used horrible words,” something that artists in Myanmar, he says, hadn’t done before, opting instead to avoid bad language altogether. The beauty of the system was that all of Big Bag’s fans could work out what swear words he was using beneath the bleeps. But turgid officials were oblivious, assuming the high-pitched monotones were a musical flourish. “Everyone knew except the censor guys.”

Kyar Pauk’s worst brush with the authorities, though, was not over his lyrics. It was a visit he made four years ago, at the suggestion of a friend, to a clinic funded by the National League for Democracy. “I went to this HIV shelter and I donated some money and medication. And they banned my music for like two months, because they don’t like that shelter because it’s supported by the NLD.

“I just wanted to give them medication, that’s all. And so no Big Bag on the radio for two months! I work at a radio station. They called me and said ‘what the fuck did you do?’” Did the ban make him nervous? “I wasn’t worried at all. My wife was. I just laughed.”

This mentality is present throughout Kyar Pauk’s music. The 2014 single Thee Khan (Kyar Pauk’s translation: “Suck it Up!”) is a rallying call to the people of Myanmar: don’t get depressed about the crappy situation you’re in. It won the People’s Choice award for freshest rock song at last year’s Myanmar Music Awards.

Inspired by his father Ringo, a famous Myanmar musician, Kyar Pauk started learning the drums at the age of four, and recorded his first song aged 13. He trained as a dental surgeon and practised for two years before leaving the profession in 2009 to devote all his time to music.

Big Bag, formed in 2003, sways from high tempo, power chord punk riffs in one song to acoustic ballads complete with finger-picking and guitar harmonics in another. Their sound has won them thousands of loyal fans, but recently all three members decided they wanted to do something different. Their latest album, We Are Big Bag, was an expression of just that, says Kyar Pauk.

Kyar Pauk, frontman of Myanmar’s Big Bag. (Joshua Carroll / Frontier)

“I used to work with a lot of producers and stuff. And every album I released, I didn’t like 100 percent. So we decided we had to do one album that we will remember for the rest of our lives. So that’s how we made that album, we put a lot of hard work in, it took lots of jam sessions, lots of writing sessions, lots of recording sessions.”

He adds, “I used to give too much of a fuck. I used to be flexible with the producers or fans suggesting you shouldn’t sing this or that. So that kind of subconsciously influences your music, whether you intend it to or not. We didn’t have that with the last album, we just did whatever the fuck we wanted.”

Thanks to that freewheeling attitude, he considers We Are Big Bag to be his greatest creative achievement so far. “Most of the albums I’ve recorded, I played the songs and then I mixed them and then felt satisfied. But then like two, three months after it’s like: ‘oh my god, I should have done this instead’. That kind of regret comes into your head. But with this album, every time I listen to it I can’t think how it’s possible to make it better.”

Big Bag’s side-project, Bloodsugar Politik, was formed with the same desire to escape the creative restrictions that come with fame. “At the time, as Big Bag we’d worked together for ten years, so were kind of a bit sick of the music and wanted to try something new, something outside of Big Bag,” he says.

“If we try something new under Big Bag’s name, the fans will be expecting what they like, so I don’t want that pressure. This is a new band name, I don’t mind if you buy it or not. This is a whole new us.”

Part of the reason behind the change in direction is a desire to leave a legacy behind. Kyar Pauk is as much a family man as he is a facetious, foul-mouthed rocker. Kids’ toys litter his yard and his two pet dogs mill around as we talk.

“It’s my age I guess,” he ponders, for a moment dropping the class clown persona. “I turned 30, and I thought I should start doing things that I will remember. Because you know, nothing lasts forever, only the memories. I want to pass something to my daughter and say, ‘this is the best album I ever made.’”