By LAETITIA VAN DEN ASSUM | FRONTIER

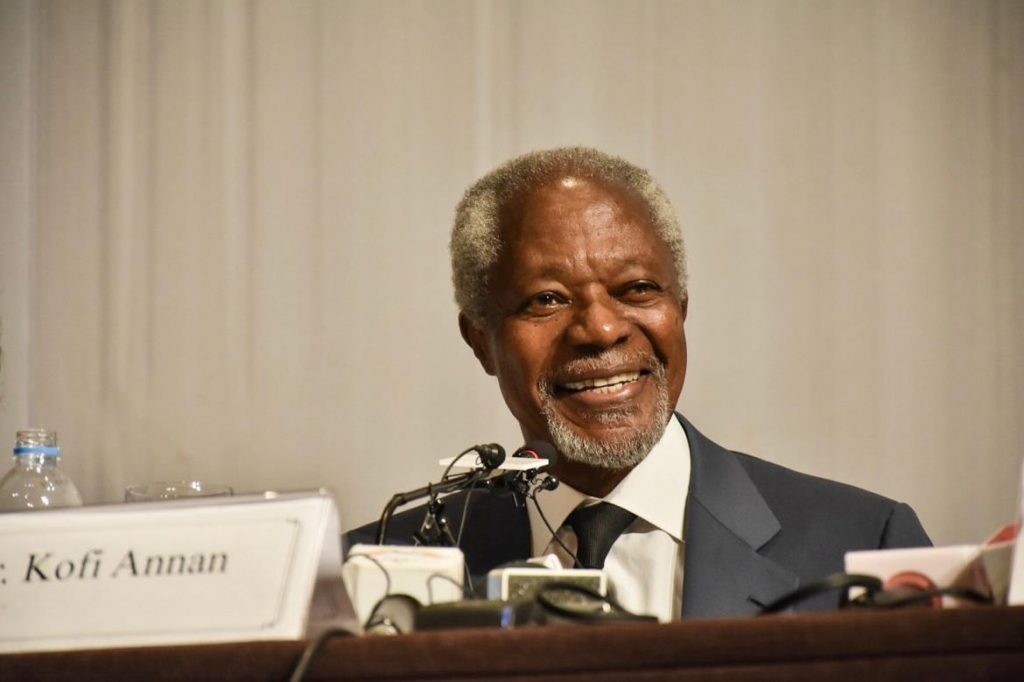

They came out of nowhere, the Rohingya women and their young children, running towards us from all directions. It was December 2016 and the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State had just arrived in Kyat Yoe Pyin village in Maungdaw District. Kofi Annan led us on this trip. We came unannounced and were observing destroyed sections of the village when the women saw us.

Our security detail tried to stop them but Annan told them not to. We were surrounded in no time and heard what had happened in the village when security forces retaliated after the deadly attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on police posts on October 9, 2016. The accounts of loss and pain were harrowing: husbands and sons who were dead, missing or arrested; sexual violence; destroyed houses, schools, mosques and markets; and lost livelihoods.

Annan stood quietly and listened. He took his time, giving the women ample opportunity to share their grief and grievances. As he wrote in his foreword to the commission’s report, “we have endeavoured to listen and learn”. And learn we did.

Not only from the Rohingya, but from all communities, particularly the Rakhine. Annan constantly underlined the importance of impartiality and our report speaks to the firm belief that change starts with communities themselves.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

During his final press conference in Myanmar, on August 25, 2017, Annan said that “the unfettered participation of all the people of Rakhine in the process of transformation … is indispensable. They must be convinced of the need for change through an inclusive dialogue that builds trust among the communities of Rakhine State, which is the foundation of lasting progress.”

He made these comments on the very day new attacks by ARSA shook Maungdaw District and at the start of disproportionate retaliation measures that drove more than 700,000 Rohingya to Bangladesh. While many feared that the commission’s final report would soon become irrelevant, they were proven wrong. Despite the dramatic change in Rakhine’s political realities, it has remained highly relevant. Its balanced approach, as well as the weight it attributes to addressing the underlying causes of the problems and grievances, has contributed to the acceptance that implementing its recommendations is a prerequisite for the successful voluntary return of refugees.

In mid-October 2017 Annan went before the UN Security Council in New York to present the commission’s findings. All 15 members of the Council welcomed the recommendations. As such the report is one of the few areas of agreement between Myanmar and the broader international community regarding the crisis in Rakhine State. But it did not end there.

Wanting to share the experience of the Rakhine Commission, Annan called for a lessons-learned project – first and foremost for Myanmar itself, but also to ensure that others might benefit from our experience in a way accessible and instructive for policy makers, academics and practitioners. The results of the study were launched on June 8, 2018 at a meeting in Copenhagen hosted by the government of Denmark and in the presence of two Myanmar government ministers.

It was clear during my short stay in Copenhagen that Annan had remained engaged and continued to follow developments in Myanmar and Bangladesh closely. He cared deeply. This was unsurprising in a man who, over many years, had spoken so often and incisively about the importance of a culture of diversity, inclusion and tolerance as opposed to ethnic and religious strife. Writing about the concept of sovereignty in his 2012 book Interventions, he reminded us that sovereignty does not only entail rights but also responsibilities. Responsibility to all those who reside in sovereign territory.

Myanmar’s transition is at a crossroads. The problems our commission encountered in Rakhine State are closely linked to developments throughout Myanmar. As the commission’s report notes: “The people of Myanmar rightly take great pride in their history and culture, which is characterized by its rich diversity. However, in order to move forward together the past must give way to a renewed vision for a dynamic future.”

How to move forward as a nation? Myanmar’s diverse people must decide their own future, and they would do well to debate what it means to be a 21st century Myanmar citizen. Cultivating a national identity based on pluralism and diversity would help in developing a vision for a dynamic future. In doing so, they would honour the legacy of Kofi Annan. May he rest in peace.