class=

For many foreign governments the struggle for a democratic Myanmar is synonymous with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The daughter of the independence hero, Bogyoke Aung San, accidentally stumbled into politics in 1988 when she returned to Myanmar to tend to her ailing mother after decades abroad. Her famous family name catapulted her into political stardom overnight. The foreign media were quick to embrace Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, whose eloquent Oxford English and femininity put her in stark contrast with the brutish, xenophobic generals, for whom she was a nemesis. She offered the media a narrative of good versus bad, white versus black that sold newspapers and was easy to comprehend.

In reality there were, of course, many shades of grey.

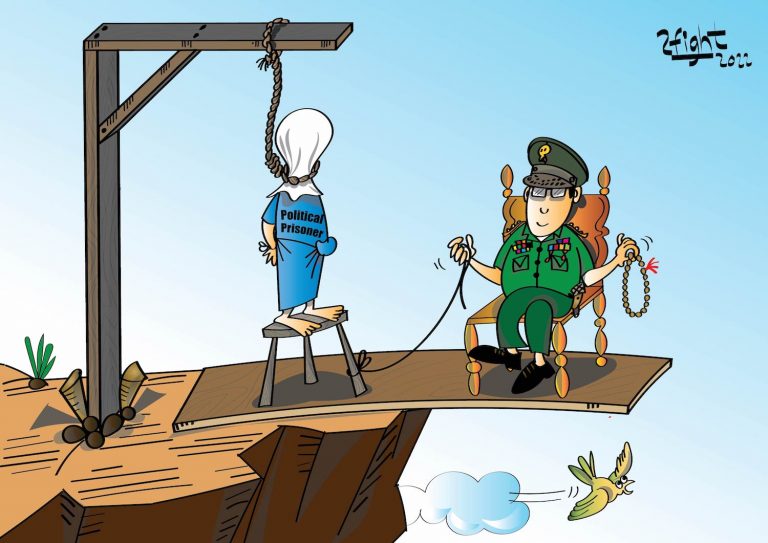

Ko Ko Gyi, a key leader of the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society, walked a different path. While Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was busy invoking the memory of her father to boost her popularity, a young Ko Ko Gyi was helping to launch a nationwide uprising that came close to toppling the military government. With fellow board member of the All Burma Federation of Students Unions, Min Ko Naing, he was involved in organising the mass protests that crippled the government apparatus and culminated in a bloodbath when the army eventually decided crack down. Both paid a hefty price for their activism. Ko Ko Gyi, the vice-chair of the ABFSU, was arrested in April 1989. He was released after 44 days and arrested again in December 1991. Min Ko Naing, the chairman of the underground student union, was kept in prison until 2005.

Ko Ko Gyi was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment with hard labour. His sentence was later reduced to 10 years, but was detained until March 2005 under a law used against those deemed a threat to the state. Special Branch knocked on his door again on September 2006. The activist spent another three months in jail, this time as a victim of the successful ‘white expression campaign,’ in which citizens were urged to complain about the military junta. The constructive criticism was unappreciated.

In January 2007, Ko Ko Gyi was released once more, allowing him to start agitating again. Six months later he marched with a handful of 88 Generation activists to protest against a sharp rise in fuel prices. The protests attracted the support of monks and escalated into the protest movement known as the Saffron Revolution, which was harshly suppressed. By then Ko Ko Gyi, Min Ko Naing and others were already under lock and key. Another ludicrous sentence was handed down: this time Ko Ko Gyi was condemned to 65 years in prison.

The prominent activist was released again in the amnesty granted to political prisoners in January 2012.

The interrogations and the long years behind bars did not break Ko Ko Gyi’s spirit. In an interview with Frontier in his apartment in Yangon’s inner Sanchaung Township, the veteran activist was guarded, weighing his words carefully, but a smile was always there.

“They don’t want any dictatorship. Look at the 1990 election and the 2012 by-election. People cast a protest vote. They will vote against the ruling party.”

Ko Ko Gyi, 51, recently became a father. His child was elsewhere but an empty cot was in the centre of a sparsely decorated living room. On the wall were portraits of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, an awkward sight, given that Ko Ko Gyi and 16 other members of the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society group had been promised positions on the candidate list of the National League for Democracy. That promise was ultimately broken by The Lady.

“I am not commenting on that,” Ko Ko Gyi said. “I have said that I will support the democratic forces in the run-up to the November 8 elections. We encourage voters to vote for our nation’s activists. They know the sacrifices that they have made. Personally, I morally support Dr Nyo Nyo Thin. She has enough experience in the Yangon Region Parliament to do well in the Pyithu Hluttaw.”

But why didn’t he decide to run as an independent?

“I don’t want to confuse the voters. And I don’t want to split the democratic forces,” Ko Ko Gyi said.

After the November 8 election, the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society leader said he plans to start his own party to compete in the 2020 elections. Three fundamental issues need to be addressed, said Ko Ko Gyi: ethnic equality, democracy, and respect for human rights.

“Without peace, we can’t guarantee democracy,” he said. “The Taunggyi conference of the ethnics in 1962, where federalism was discussed, triggered the military coup. After that the army established their rule on the basis of an ideology of non-disintegration of the country. So it is important that we address the civil-military relation. It seems the army now accepts the terminology, but which version of federalism are they actually embracing?”

Ko Ko Gyi said he wanted to start a dialogue with the Tatmadaw convince it to allow a gradual process of constitutional reform. “If we like it or not this transition is taking place under the 2008 Constitution. The parliamentary process is not the only solution, we need a dialogue outside of parliament as well, with the army and armed ethnic groups. Key is that we amend the constitutional amendment procedure.”

“The word ‘army’ is very broad,” he said. “The transition has been designed by the previous army leadership. I have many lower ranked friends in the army, they are so poor. The 2008 Constitution was adopted without a political pact between the army and the opposition. The same goes for the 2010 election and the 2012 by-elections. And it seems the NLD doesn’t have an agreement for the post-election period this time around, although we urged the NLD to work with the ethnics. I think the best way forward would be to form a national government. We have to find common ground.”

Will the new political party have an overarching ideology?

Ko Ko Gyi launched into a history lesson on the left-leaning tendencies of the students who started the independence movement and of the Anti Fascist People’s Freedom League that ruled the country after it regained independence in 1948. The new party will be left wing as well, he said. “But I don’t want to discuss this in advance. We’re still discussing ideology. People from different quarters in society will take part, among them some 88 Generation leaders. Min Ko Naing will not enter politics. He will focus on our civil society work.”

The party does not intend to blame and shame former military officials. “We should put ourselves in their shoes and emphasise that we are not out to get them.”

Ko Ko Gyi predicted that the opposition would perform strongly on November 8 election, mainly because the Myanmar people are still very emotional about the years under junta rule. “They don’t want any dictatorship. Look at the 1990 election and the 2012 by-election. People cast a protest vote. They will vote against the ruling party.”

In the run-up to the election the inaccuracies in the voter lists have been a huge problem, said Ko Ko Gyi. He also expressed concern about the intimidating presence at polling stations of 40,000-strong special police auxiliary force, whose deployment might benefit the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party. Election observers will focus on rural areas, but it is hard to predict what will happen in the conflict areas, he said.

The Union Election Commission attracted criticism when it disqualified most Muslim candidates. In a surprise development last week, 11 Muslim candidates were reinstated. What does Ko Ko Gyi think about the USDP and NLD not fielding any Muslim candidates, and that the UEC has erased independent Muslim candidates from the process?

“According to the existing laws, the UEC had to reject some of the Muslims,” Ko Ko Gyi said. “This is also done to avoid misunderstandings, confusion and friction during the election campaign.”

Nationalists Buddhists in Rakhine and the controversial monk-led Ma Ba Tha movement have agitated against Muslims. During the last two weeks Ma Ba Tha has been celebrating the adoption of the four so-called race and religion laws, which it drafted. The laws don’t mention Muslims, but their provisions are clearly aimed at this religious minority.

What does Ko Ko Gyi think of the upsurge of Bamar chauvinism and nationalism?

“The British brought in many Indian tribes,” he said. “This fueled nationalistic feelings. Nowadays some people worry about demographic trends. The birth rates of some groups are accelerating, while other groups slow down. From a Buddhist community point of view this is worrying. We need to understand their worries. But ultimately the real problem is the citizenship issue.”

Earlier this year more than a million temporary citizenship documents, known as white cards, were revoked. Most of them where held by Rohingya Muslims, who lost the right to vote and are basically stateless. How does Ko Ko Gyi view citizenship issues?

The veteran activist pondered the question before answering.

“I think all citizens should enjoy equal rights,” Ko Ko Gyi said. “Every ethnicity should be loyal to the country, and we should search for a unified identity. Yes, the white cards were revoked. So nobody knows exactly what the status of these people is. Some hold a pink card, which is not proof of citizenship, but only a citizen scrutiny card,” he said.

“I feel the law should be upheld by the government. This is not an issue in Kachin or Shan State, where ethnic Shan and Kachin have been living for decades. Their ethnicity and citizenship are fact. The problem is Rakhine. The government organised a census last year and some people declined to register as Bengali. They can easily get citizenship, but they’re claiming the ethnic identity of Rohingya. Well, even our native people born in Thailand don’t get Thai citizenship. And our country has no official refugee policy. So how can we verify who is a migrant or a refugee?”