Myanmar has six criminal defamation laws and a study has found that their misuse by the rich and powerful is hampering the fight against corruption.

By OLIVER SPENCER and YIN YADANAR THEIN | FRONTIER

THE NATIONAL League for Democracy pledged in its 2015 election manifesto to establish a society free from corruption. Since taking office nearly three years ago, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s government has banned public officials from accepting expensive “gifts” and beefed up the Anti-Corruption Commission. But still Myanmar languishes among the world’s most corrupt countries.

The government’s moves, welcome as they are, mask an underlying flaw in its response: the surreptitious and still expanding framework of criminal defamation laws that protect the corrupt from being held accountable. Who, after all, is brave enough to complain about corruption knowing that they risk being sent to prison for up to three years as a consequence?

Many people are aware of Yangon Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein’s defamation case against Eleven Media for reporting that he was wearing a US$100,000 watch. But there have been other examples, most of them unreported. In August 2018, a Facebook user was arrested by police after he sarcastically posted a “good luck” message to them regarding their alleged attempts to sell drugs from a police station. In August 2017, a journalist posted that a minister was misusing his position to gift land to his son, but later apologised to avoid legal action.

In each of these cases, and in many others, we will never know the extent to which the allegations are true or false because criminal law requires the state to automatically support those claiming to have been defamed. If defamation is a criminal offence, then the state has an obligation to use police to investigate and state prosecutors to fight the case in court, whereas if it is a civil matter it is up to the aggrieved to hire a lawyer and find evidence. Faced with the sheer muscle of the state and its bottomless budget, who can blame a complainant for withdrawing their complaint?

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

It is likely that such situations are the tip of the iceberg. Imagine how many people have considered making an allegation of corruption but have been put off for fear of going to prison for defamation.

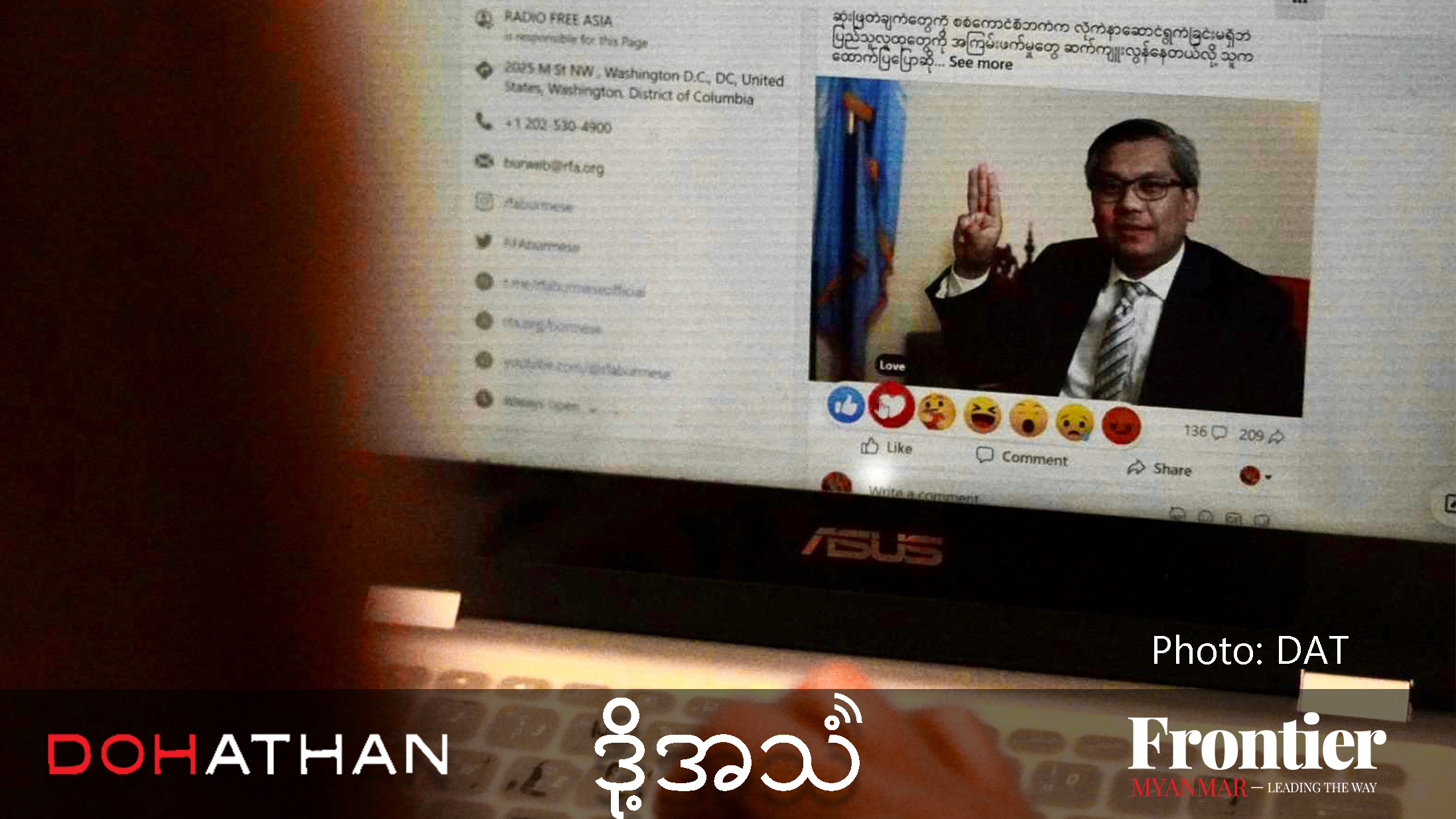

Section 66(d) of the 2013 Telecommunications Law is the public byword for illegitimate defamation cases. However, Myanmar has no less than six criminal defamation laws, all of which can and are being used by unscrupulous persons to both threaten and punish those who make allegations of corruption. This includes the Anti-Corruption Law itself, which criminalises defamation under article 46.

The first of Myanmar’s criminal defamation laws, contained within the Penal Code, was adopted by the British 158 years ago. A second was passed by the military government (Electronic Transactions Law), and another three were enacted under the previous Union Solidarity and Development Party government (Telecommunications Law, Anti-Corruption Law and News Media Law). The sixth was created by the NLD in 2017, hidden within the Law Protecting the Security and Privacy of Citizens.

A new study by Free Expression Myanmar in partnership with eight other organisations finds that defamation is misused by courts, which protect feelings rather than reputations, ignore defences, punish criticism of public officials and politicians, delay, and always apply the most punitive sanctions possible.

The study, Defamation: International standards and Myanmar’s legal framework, looks in detail at each of the six laws, identifying their faults and how they have been collectively misused and abused over the past two years, while elaborating on what democratic standards a new civil law needs to fulfil.

The civil society coalition that came together to campaign against 66(d) has set its sights on the entire criminal defamation framework, including the threat of a possible seventh criminal defamation law potentially concealed within the draft cyber crime bill being developed by the government.

There is concern that, after all civil society’s work, if one law is improved then unscrupulous persons will start using the other laws in its place. When 66(d) was slightly amended, complaints were filed under other more punitive laws, such as the Law Protecting the Security and Privacy of Citizens, which actually enables potentially longer prison terms for those who are convicted.

Instead of amendments, civil society wants decriminalisation. A civil defamation law that overrides all the others has two immediate benefits for the public. First, it will stop the powerful from blatantly exploiting taxpayers’ money to pay for their illegitimate defamation complaints because they will have to pay for their own lawyers.

Second, for those who have been unfairly harmed by defamation, any money awarded by a court will go directly to them to compensate for their loss of reputation, and not to the government’s coffers, as currently occurs.

This is not to say that decriminalisation is a perfect answer. Free Expression Myanmar’s report outlines what safeguards a civil defamation law should include in order not to follow the path of Singapore or the Philippines, where activists and media outlets are bankrupted by excessive awards unrelated to any actual harm.

In recent meetings with MPs and the Anti-Corruption Commission, the civil society coalition presented disturbing evidence about how corruption allegations are being stifled. Lawmakers and commission members agreed to consider further proposals.

Now the NLD-controlled legislature and government are faced with the choice of continuing their support for Myanmar’s excessive criminal defamation laws, or fulfilling the NLD’s manifesto pledge of establishing a society free from corruption.