It’s been a gruelling few weeks for students sitting the all-important matriculation exam, regarded as a crucial step towards achieving a successful life and career.

Words & Photos ANN WANG | FRONTIER

Hundreds of thousands of students throughout Myanmar sit their matriculation exam in mid-March every year. The pass rate last year was a record 37 percent, the highest in five years. Factors such as low quality education, limited access to schools and the exam system itself contribute to the result. However, many believe that passing the exam and entering university is their only option for a better life.

Maung Set Kaung San’s text books and practice books are spread across the coffee table in his living room. The 15 year-old-from Bago Region was among the 671,437 students registered to sit the matriculation exam this year. “It’s a life-changing exam,” said a nervous but excited Set Kaung San. As the son of the teacher, he felt obligated to pass the exam.

Ma Chaw Su Wai, centre, with her friends outside her school in Bago Region. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Depending on their major, each student takes exams in about eight to 12 subjects over two weeks. It’s one exam a day and three hours for each exam. To matriculate, students need to score at least 40 out of 100 in each exam. Students who fail have the choice of retaking the exam in following years until they pass. The results are usually released in June.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

About 70,000 students who registered this year failed to attend the matriculation exam, a senior official at the Education Ministry’s Examination Department said. There are many reasons why students do not attend their exams, he told the Myanmar Times. Some students do not sit exams because they are not satisfied with their preparation and want to try again the following year.

Set Kaung San, who dreams of majoring in veterinary science at university, is worried about how he will perform in the exams. He said there are too many subjects to study and that compared with the exams he sat during the year, the matriculation exam is much harder.

Students sit and study outside the Basic Education High School 8 in Bago. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

The exams set during the year are usually based on text books that students are encouraged to memorise, but for Set Kaung San the matriculation exam has been particularly difficult. “For the matriculation exam reading the text books is not enough,” he said, adding that some of the exam questions were totally unexpected.

Myanmar’s standardised exams and examination system based on rote-learning have long been criticised by education reformers. Cliff Meyers, the head of the education section with UNICEF Myanmar, said the danger of standardised exams was that they involved teaching for a test. Most exams in Myanmar are based on rote memorisation, which has a real impact on what is taught and how it is taught, he said.

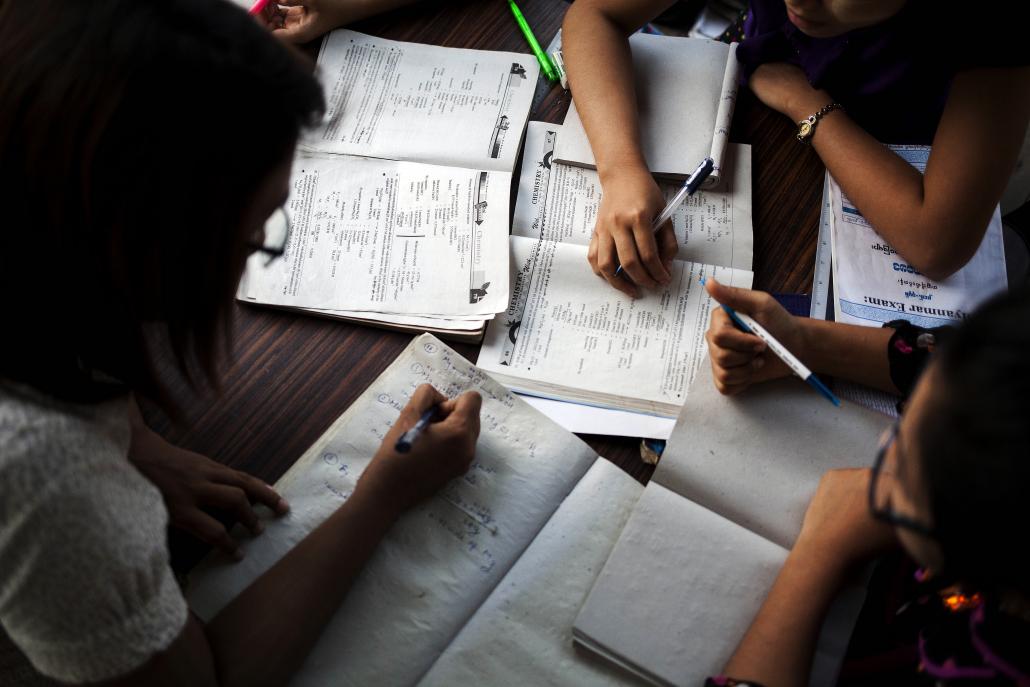

Students studying for Myanmar’s matriculation exam. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Meyers’ observation was echoed by Set Kaung San’s mother, who has been a high school teacher for 37 years and did not want to be named. “Students don’t need to study outside knowledge, have critical thinking skills or the ability to be creative in order to pass the exam. They just need to learn from the textbooks and repeat it in the exam,” she said.

“But with this approach, can the students really understand their lessons?” she said.

Set Kaung San is confident he will pass the exam, because he has studied hard during the past year and spent the three-month summer break attending private tutorial classes that can be critical for a student to matriculate.

Ma Chaw Su Wai on her way to school in Bago. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Of those who sit the exam, only an average of 30 percent will pass. The 37 percent pass rate in 2015 was the highest in the last five years. Ayeyarwady Region had the highest national pass rate, at 36 percent, and Chin State the lowest, at 17.28 percent. For disabled students who sat the exam, the pass rate in six of the 14 states and regions was zero percent.

A 37 percent pass rate is a welcome development for U Myo Nyunt, the director-general of the Examination Department. He said the pass rate had risen in the last few years, a trend he attributed to the efforts of students and the support of parents. However, Myo Nyunt believes it is misleading to place emphasis on the pass rate because students in Myanmar have only one choice of exam.

“Myanmar only has a standardised exam for basic education system, no vocational or technology education nor an exam designed for alternative education,” he said. Myo Nyunt believes more channels should be created for students, but acknowledges that the future of exam reform rests with the National League for Democracy government.

A student studies in the stairwell at BEHS 8 in Bago. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Mr Meyers laments the 37 percent pass rate but said the real shock is that so few students were able to complete their secondary education and sit the matriculation exam. UNICEF figures show that 73 percent of pupils complete their primary education but an average of only 25 percent of students complete secondary school.

Tim Aye-Hardy knows first hand what is causing the high drop-out rate among students in Myanmar. Mr Aye-Hardy is the founder of the Myanmar Mobile Education Project, myME, that provides after-hours education for tea shop workers and other child labourers in Yangon and Mandalay. “Poverty has a real impact on the kids,” he said.

Some students cannot afford the cost of transport to school and many choose to begin work at an early age to help support their families. Another factor is a lack of access to education because many villages do not have schools. The MyME project focuses on vocational training instead of a formal curriculum, but of its 15 students taking the matriculation exam this year, Mr Aye-Hardy estimates that probably only two have the ability to pass.

Ma Chaw Su Wai at home with her mother. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Ma Chaw Su Wai, 17, whose family has farmed in Bago Region for generations, is the only one of four siblings to study at high school to matriculation level. She believes that passing the exam will improve her life and her goal is to attend Yangon University of Economics.

Asked if she believed she would pass, Chaw Su Wai paused from reading her chemistry text book out loud and quickly nodded her head, before refocusing her attention on reviewing the book for her upcoming exam.