The Young Men’s Buddhist Association promised to end its involvement in politics after the nation achieved independence, but there are signs it might be changing its mind.

By HEIN THAR | FRONTIER

Formed in 1906, the Young Men’s Buddhist Association played an active and important role in the campaign for independence. When that goal was achieved in 1948, it stepped back from the stage and pledged to never again be involved in politics.

Over the years, it stuck closely to its vow. But there are now indications that the YMBA may be planning a return to the political arena.

Its recent activities have included conferring its highest awards on Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and appointing him as the association’s lifelong patron.

The YMBA has also recently developed a relationship with former members of a hardline Buddhist nationalist group, the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion. Better known by its Burmese acronym Ma Ba Tha, the group was banned by the supreme body representing the monkhood, the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, in May 2017.

The YMBA’s awarding of Min Aung Hlaing and its relationship with former Ma Ba Tha members have aroused curiosity and suspicion, particularly given the senior general’s reported political aspirations and the fact Myanmar is on the eve of a general election.

But association chair U Ye Htun insists the YMBA will never return to politics. He said the association was focused only on activities to “promote race, religion, the Buddha’s teachings and education”, reflecting the organisation’s motto.

He declined to be interviewed at length, despite Frontier visiting the YMBA office numerous times in recent months, and refused to answer many questions on the association’s recent activities.

“Come back next year, when 2020 is over – we will not do anything this year,” he told Frontier on July 22.

The anti-colonial struggle

Although it has eschewed politics for most of its history, the YMBA was created as part of a pan-national movement against colonialism.

The founders of the YMBA, who included noted nationalists like U Ba Pe, U Maung Gyi and Dr Ba Yin, took inspiration from their counterparts in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), who had set up a YMBA in 1898 modelled on the Young Men’s Christian Association.

The organisation rose to national prominence in 1917 when it launched a campaign against the wearing of shoes at pagodas. The campaign was essentially anti-colonial, because it was foreigners – particularly the British rulers – who refused to take off their footwear at pagodas, deeply offending local Buddhists.

The campaign was considered a success, and three years later the YMBA joined the student strike that led to the creation of Rangoon University and other concessions from the British, an event marked annually as National Day.

But the YMBA soon began to attract criticism. Later in 1920, internal disputes emerged and the association entered a long period of instability and decline. It was soon dubbed by journalists as the Young Men’s Beer Association, suggesting the organisation was more focused on socialising than propagating Buddhism.

In 1938, as a new generation of student activists were beginning to emerge and press for independence, U Thein Maung, a former mayor of Yangon (then Rangoon), reformed the YMBA again and helped to revive its reputation to some extent.

Despite its years of involvement in the politics of independence, the leadership of the YMBA announced after the British left in 1948 that the organisation would from that point forward focus only on amyo (race), batha (religion), sasana (the Buddha’s teachings) and pyinnya (education).

In the years since independence, the YMBA has stuck closely to its vow to stay out of politics. It has conducted many short courses in Buddhism and has presented awards honouring monks and laity.

Although the YMBA remained one of the country’s biggest faith-based organisations and the school curriculum taught generations of children about its role in Myanmar history, the association’s public profile gradually faded.

When it was in the news, it was often for the wrong reasons. In 2014 some of its leading members were expelled amid allegations that funds had been misused, and subsequent infighting between senior members paralysed the organisation for more than a year. Senior YMBA officials declined to comment to Frontier about this internal conflict.

When the YMBA was finally able to hold an annual conference in January 2016, it selected a member named U Tin Win as its new chair. The current chair, Ye Htun, took over in early 2019.

Patron for life

In October 2019, the YMBA burst back onto the stage when it presented Tatmadaw chief Min Aung Hlaing with its Maha Mingala Dhamma Zawtika Daza award and made him the association’s patron for life.

The senior general received the prize in recognition for his support for Buddhism, role as guardian of the nation, and for living in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings, the association said.

The senior general returned to the YMBA later the same month to give a speech to members.

Then, in February this year, the YMBA bestowed on Min Aung Hlaing its highest award, the Agga Maha Mingalar Zawtika Daza.

“We gave him that award because he really deserved it,” YMBA chair Ye Htun told Frontier.

The senior general had continuously supported race, religion, the Buddha’s teaching and education, Ye Tun said, adding that Min Aung Hlaing had protected Myanmar and its people from threats.

Although it was not explicitly mentioned, the award appears to have been prompted in part by his leadership of the campaign against the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, a Rohingya insurgent group, in Rakhine State since the group launched coordinated attacks on security posts in 2016.

Following larger-scale ARSA attacks on police and military posts in August 2017, Min Aung Hlaing ordered a Tatmadaw clearance operation that forced around 750,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Thousands were allegedly killed, and soldiers were accused of gang rape, torture and looting. Hundreds of Rohingya villages were burned to the ground.

A United Nations Fact-Finding Mission set up to investigate the Tatmadaw’s actions said in 2018 that there was enough evidence to investigate and prosecute Min Aung Hlaing and other senior military officials for genocide. In December 2019, the International Court of Justice began hearing a case against Myanmar alleging that it was responsible for genocide against the Rohingya.

The United States, European Union and some other Western countries have also placed sanctions on Min Aung Hlaing, imposing asset freezes and travel bans in their jurisdictions and prohibiting companies from doing business with him.

But among nationalist groups that have long warned that Muslims – and particularly the Rohingya – pose a threat to Myanmar, the military’s operations in Rakhine have made Min Aung Hlaing a hero.

Association secretary U Thaung Win said the senior general had a long relationship with the YMBA, and had often come to its office when he was young.

Membership drive

But the YMBA hasn’t just been handing out awards to Myanmar’s controversial commander-in-chief.

Although Ye Htun insisted that the YMBA was “not doing anything this year”, the group has been signing up new members and opening branches.

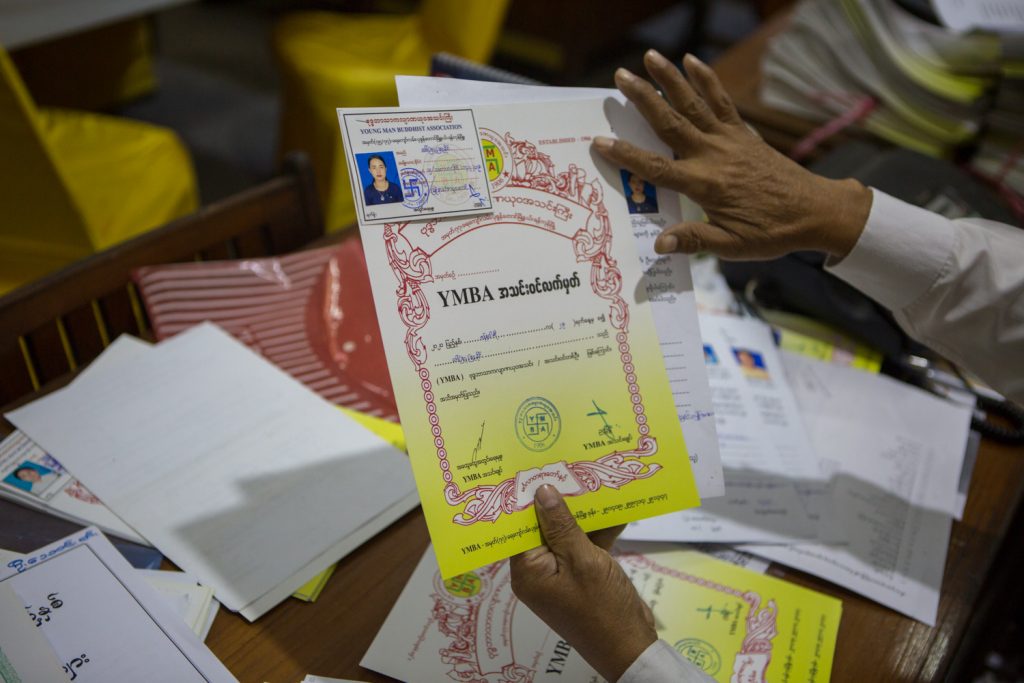

Secretary Thaung Win said the organisation had launched a drive in 2019 to expand its current membership of 30,000.

Membership costs K2,000, although the fee for Tatmadaw members is K1,500, according to a June post on the YMBA’s website.

When Frontier visited the YMBA’s head office in Yangon’s Pazundaung Township in May, it saw hundreds of membership applications that had been sent in from around the country.

“We will accept all Buddhists as members in line with the association’s rules,” said Thaung Win, a former military officer who later served at the Ministry of Information.

The membership includes present and former members of the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party and monks who had been involved with Ma Ba Tha.

A former joint secretary of Ma Ba Tha, the Mya Taung Sayadaw, was a guest speaker at a ceremony to open a YMBA branch in Ayeyarwady Region’s Kyaunggon Township in February.

In the 2015 election, Mya Taung Sayadaw campaigned for the USDP, warning that the National League for Democracy was the party of “Islamists” and would “destroy the race and religion”. At the branch opening earlier this year, he used inflammatory language about the Rohingya and spoke about other popular nationalist causes.

Another of the YMBA’s new branch offices was opened in Yangon’s Insein Township in March.

The branch is chaired by the former USDP township chair, U Tint Lwin, who joined the YMBA in February. He told Frontier in a July 23 interview there are more than 100 members in the township.

Despite being “a former member of a major party”, Tint Lwin said he would “not campaign for it while serving the YMBA”.

“But as a voter, I want to suggest that people vote for the party that can promote race, religion and sasana,” he said.

Yangon-based Khit Thit Media reported on February 27 that the YMBA also has a close connection with a new hardline Buddhist group known in English as the Myanmar National Organisation. The report said MNO members have attended YMBA meetings and events.

The MNO was reportedly founded in January and includes former Ma Ba Tha members and supporters of the firebrand monk U Wirathu, who went into hiding in May last year after being charged with sedition.

Members of the MNO are believed to have been among those who assaulted youth activists demonstrating in support of peace in Yangon’s Tarmwe Township in May 2018, Khit Thit Media reported.

Little else is known about the MNO, which does not appear to have a website, Facebook page or office.

Both Ye Tun and Thaung Win declined to comment on links to the USDP, Ma Ba Tha or the MNO.

Asked about the YMBA’s alleged links to the MNO, Tint Lwin said, “We will work with any organisation that shares the same goals of fighting for race, religion and the Buddha’s teachings.”

The YMBA is also planning to expand its headquarters, replacing its two-storey office on Ye Kyaw Street with a building of up to six stories. The association’s leaders hope to use the extra space to generate income, such as by renting parts of it out for weddings.

Thaung Win said the YMBA has enlisted the senior general’s help for the plan.

“We have no other business, we do not take foreign aid, we rely on donations,” he said.

A future in “national” politics?

The apparently close relationship between the YMBA, Buddhist nationalist groups, former USDP members and the commander-in-chief has raised suspicions that the association might be planning a return to politics after more than seven decades.

On social media, the YMBA has come in for significant criticism, particularly due to its decision to give Min Aung Hlaing the awards and make him patron for life.

“Is YMBA using Min Aung Hlaing’s image or is Min Aung Hlaing using YMBA?” commented one Facebook user. “Regardless, religious problems are always easy to start in Myanmar.”

Secretary Thaung Win said that although the YMBA had pledged after independence not to be involved in politics, this referred only to “party politics”. Instead, it wanted to participate in “national politics”, he said, invoking language used regularly by Min Aung Hlaing to justify that Tatmadaw’s continued role in Myanmar’s political life.

In a speech to mark Armed Forces Day in 2017, Min Aung Hlaing said that history had shown “putting too much emphasis on party politics doesn’t lead to any stability [in] the country, but [giving] priority [to] national politics can only bring stability”.

The Tatmadaw’s role in “national politics”, as Min Aung Hlaing has explained it, is as a guardian of Myanmar’s fledgling democracy from squabbling politicians and secessionist armed groups.

In an interview in June with Russian media outlet Arguments and Facts, Min Aung Hlaing again reiterated that the Tatmadaw would leave politics, including giving up its 25 percent bloc of seats in parliament, only when there was political maturity and peace.

But he also hinted that he might have a political career after his scheduled retirement as commander-in-chief next year. In a transcript of the interview posted to military-owned media outlet Myawady, Min Aung Hlaing played up his “political” and “administrative” experience.

“I have served the interest of the people and country and will continue to do the same in the future by considering how I can help and what I can do for the people and the country,” he was quoted as saying.

There are no indications that the YMBA is seeking to influence this year’s election, scheduled for November 8. But its efforts this year to expand its membership, headquarters and branches, and its recent alignment with nationalist groups and Min Aung Hlaing, could lay the foundations for a future political role.

A former senior member of the YMBA who declined to be identified expressed disappointment at the direction it had taken under the current leadership.

“I feel sorrow for a great organisation that had a great reputation,” he said. “It is not clear if the YMBA is trying to become involved in politics or if dishonest politicians are trying to use the image of the YMBA for their advantage.”