Concerns are once again emerging over the future of the National League for Democracy, amid doubts over its commitment to democratic principles.

By NYAN HLAING LYNN | FRONTIER

ONLY TWO political parties in Myanmar have had the support of an overwhelming majority of the people in fair elections: the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League led by the hero of independence, General Aung San, and the National League for Democracy, conceived during the struggle for democracy 28 years ago and headed by his daughter, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

The NLD was formed on September 27, 1988, in the aftermath of the 8.8.88 national uprising that came close to toppling General Ne Win’s Burma Socialist Program Party government. The uprising was brutally quashed after the military ousted the BSPP regime in a coup on September 18, 1988 and a junta ruled the country until 2011.

For the NLD, the long road to democracy has been no bed of roses. Party members and sympathisers have endured unimaginable persecution, hardship and suffering. Many received 20-year jail terms and experienced horrific torture. Some died in prison.

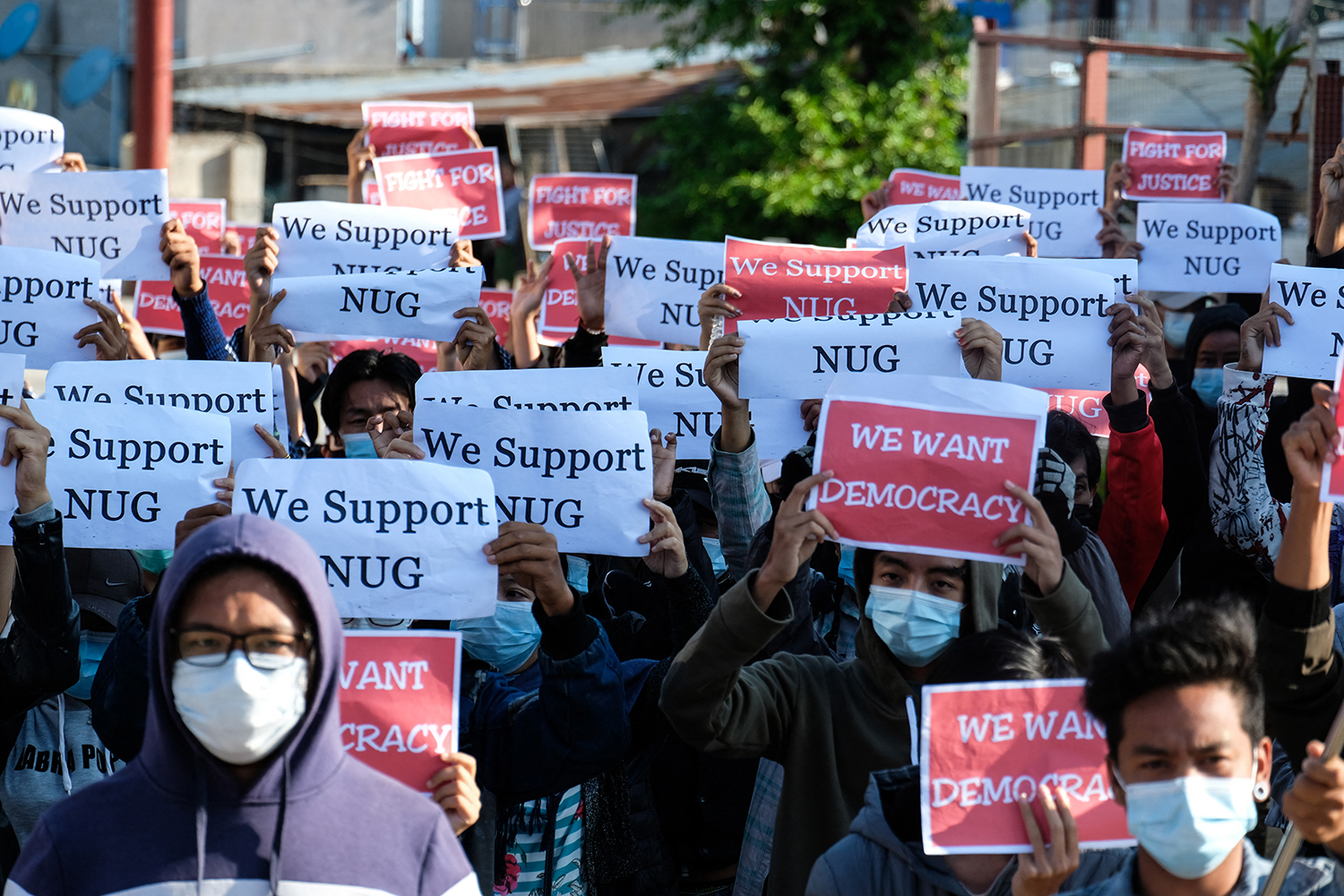

Young National League for Democracy supporters at a rally in Yangon on October 10, 2015. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The NLD achieved decisive victories in two of the three national elections it has contested since the 8.8.88 uprising. In the 1990 election held under the State Law and Order Restoration Council, the NLD won 81 percent of the seats but the junta refused to honour the result.

In the 2015 election it won 79 percent of the elected seats, about the same as the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party did in the flawed 2010 election, that the NLD boycotted. The NLD had returned to the political area in by-elections in 2012, when it triumphed in 43 of the 44 seats it contested, including the Pyithu Hluttaw seat of Kawhmu, in Yangon Region, won by Aung San Suu Kyi.

Many regard last year’s landslide election victory as a triumph for the NLD and the people’s hopes for a return to democracy.

Political analyst Dr Yan Myo Thein says the NLD had achieved political dominance “because of the hard work of party members at the grassroots level who want to change the country led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi”.

However, there are some among the party’s legions of members and supporters who are concerned about its apparent lack of preparation to tackle important future issues, including the inevitable need for new leadership.

They have good reason to be concerned. Since it was formed 28 years ago the party has grown to more than four million members. During that time the NLD has had only one national congress, in Yangon in March 2013 – such a gathering was impossible under junta rule – resulting in the selection of a 120-member central committee and a 15-member central executive committee.

It is a cause of disquiet among some NLD members that the larger CC has not met for nearly 10 months.

A man walks past a graffiti depiction of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi outside the National League for Democracy headquarters in Yangon on November 13, 2015. (Nicolas Asfouri / AFP)

In the aftermath of the recent dismissal of the party chairman in Shan State’s Taunggyi District branch, concern has also risen over the handling of internal disputes. In such a situation, State Counsellor, Foreign Minister and Minister for the President’s Office Aung San Suu Kyi is inhibited from intervening because the 2008 Constitution bans those in government from involvement in “party activities”.

About a month before the change of power in late March, the party created a mechanism for handling disputes and disciplinary matters, establishing a five-member secretariat comprised of senior CEC members: U Win Htein, a longtime confidante of Aung San Suu Kyi; Pyithu Hluttaw speaker U Win Myint; Mandalay Region Chief Minister Dr Zaw Myint Maung; U Nyan Win; and U Han Thar Myint, who headed the party’s economic committee.

The authority of each secretariat member was not clearly defined. This has resulted in tensions at senior levels of the NLD after Win Htein travelled to the Taungyyi, the Shan State capital, earlier this month, to reshape the state-level Central Executive Committee, whose members were accused of not doing enough to support NLD candidates in last year’s election.

According to senior party officials, the state branch leadership was upset at the headquarters’ choice of candidates for the election. The NLD fared poorly in Shan State, winning 15 of 60 seats in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw and just 23 of 103 seats in the state hluttaw.

During his visit to Taunggyi, Win Htein removed five members from the state-level central executive committee, including its chair, Daw Khin Moe Moe. A veteran party member, she had served as secretary of the NLD’s Taunggyi Township branch since 1988. In 2013, Khin Moe Moe was elected to the state CEC and made branch chair.

The demotions prompted the Taunggyi district branch chair, U Tin Maung Toe, to allege in a post on Facebook that positions on the party’s executive committee in Shan State could be bought. In response, Win Htein summarily dismissed Tin Maung Toe from the party.

Khin Moe Moe, who is also a member of the national-level Central Committee, said she had appealed against her demotion to the NLD’s central disciplinary committee, arguing that the decision did not conform to party rules.

“The rules say that if I do something wrong and someone complains, party disciplinary committees at various levels are required to investigate, but that is not what happened,” she told Frontier. “The statement said I was dismissed as chairperson of Shan State, so it is not clear if I am still a member of the CEC.

“Senior party leaders should adhere to the rules and rules must be firm.”

Despite the rules about the role of disciplinary committees, the demotion of the five state branch members and summary dismissal of Tin Maung Toe was approved at a CEC meeting in Nay Pyi Taw on September 11.

One absentee from the CEC meeting – due to illness – was the chair of the disciplinary committee, Nyan Win. He confirmed to Frontier that the disciplinary committee, established on April 29, 2013, had not investigated the Taunggyi case. The decision was made by the CEC, he said, but should have first been investigated by the disciplinary committee.

Supporters of the NLD gather outside the party’s headquarters in Yangon on November 9, 2015, the day after the party’s landslide victory. (Romeo Gacad / AFP)

The NLD has five-member disciplinary committees at the state and regional level and the central disciplinary committee comprises two national-level CEC members, two national CC members and a head of office.

Win Htein, who is not a member of the central disciplinary committee, told Frontier that he had to tackle the Taunggyi case because no one else did.

“The disciplinary committee should have investigated the Taunggyi case before the election,” he said.

Yan Myo Thein said the fracas over disciplinary procedures showed that the NLD needed to focus more attention on amending its procedural rules.

Meanwhile, in an indication of organisational challenges, the party is yet to complete the election of branch leaders at ward or village, township, district and state and regional levels. The NLD central committee had stipulated that the elections, that began on June 15, were to be completed by an August 14 deadline.

“The elections were finished at township and district level before the deadline, but there’s about 10 percent left to do at ward or village level,” said Dr Nyi Nyi Zaw, joint-secretary of the Nay Pyi Taw District branch.

Another issue concerning some party members is the lack of attention to grooming a new generation of leaders.

Despite a party directive on June 14 to reorganise its youth wing, including reducing the age limit from 35 to 30, a plan has yet to emerge. Dr Wai Phyo Aung, 32, the joint-chairman of the youth working group-central, there were no plans to hold another youth congress.

The first such congress took place in August 2014. Afterward, about 5,000 youth working groups were established in the states and regions, as well as a 15-member central youth working group. Wai Phyo Aung said the youth working groups had a total membership of about 100,000.

Ma Zar Chi Myint, a 31-year-old member of the youth wing, said capacity-building training was being provided in Yangon but not yet in the states and regions.

Youth wing members said they joined the NLD because they believe in Aung San Suu Kyi, support the party’s policies and want to be involved in the democratic transition. There was no generation gap problem in the party, they said.

“Young wing members are too enthusiastic, so the older generation needs to be in charge in case the young ones make mistakes,” Zar Chi Myint said.

Critics of the NLD say that it is still weak as a political party and worry that it is not doing more to prepare for a post-Aung San Suu Kyi era.

“Frankly speaking, it is like an iceberg; a large part under water may be cracked,” U Myint Maung Maung, principal of an English-language school in Taunggyi told Frontier.

Yan Myo Thein said the overwhelming public support for the NLD made him worry for the country’s future. “It is time the NLD built a party based on policy,” he said.

“If anything goes wrong in the party, it could have an immense impact on the country and the peoples’ yearning for democracy. Party leaders must accept this and begin building the party according to democratic principles,” he said.

It’s a challenge that senior NLD officials acknowledge, but seem unable to tackle.

Senior NLD official U Win Htein speaks to Frontier prior to last year’s election. He has been accused of failing to follow party rules following the summary sacking of a party member in Shan State and demotion of five others. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Perhaps that’s because of the perception that the NLD as a party and in government is ruled from the top and one of its weaknesses in an apparent inability to delegate.

“One challenge for the NLD as the party in government is to adapt to the role of exercising leadership,” said Mr Trevor Wilson, a visiting fellow at the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University and a former Australian ambassador to Myanmar.

He said “exercising leadership” would require using whatever expertise or inspiration NLD government ministers had to guide and inform policy decisions. It also meant being prepared to draw on the support and goodwill of outsiders in situations where technical or specialist expertise was needed.

“There is nothing wrong with this,” Wilson told Frontier by email. “That is what governments around the world do with the help of bureaucrats who are not necessarily politically motivated, but would normally be very supportive, and occasionally even creative, about what to do [based on their experience or specialist knowhow].”

In a report in late July, Brussels-based think-tank the International Crisis Group said Aung San Suu Kyi had assumed a “potentially overwhelming workload” in the new government and its success would partly depend on her ability to delegate.

“Success depends on twin policy and personal challenges: developing not only considered and consultative approaches, but also her ability to delegate,” the ICG said in the report, Myanmar’s new government: Finding its feet.

Win Htein said the future success of the NLD depended on Aung San Suu Kyi’s participation in political activities because the party could not win elections without her.

“The party has become strong under her leadership … everything will be smooth if she leads,” he said.

Asked how the NLD intended to prepare for the time when Aung San Suu Kyi is no longer its leader, Win Htein said: “I’m sorry, I can’t answer that question.”

Top photo: Young supporters of the National League for Democracy at a Yangon election rally on October 10, 2015. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)