By KELLY MACNAMARA & ATHENS ZAW ZAW | AFP

YANGON — Inside the graceful halls of Myanmar’s first modern bourse a huddle of business leaders crowds into a crash course on sharetrading, as the former junta-run country takes another leap towards economic revitalisation.

The Yangon Stock Exchange (YSX) is due to debut its first listed company on Friday, just days before a new civilian government overseen by Aung San Suu Kyi comes to power in a nation fast opening up after decades of military rule.

The start of trading, long after the bourse was first envisaged, is a vivid illustration of Myanmar’s economic handicap — a country that still has no credit rating and where business has long been hamstrung by ingrained corruption.

But it also encapsulates the excitement and optimism that has gripped both local and foreign investors alike.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Dozens of people every week have attended the YSX classes for those unfamiliar with sharetrading, which include lessons on investment risks and rewards as well as multimedia guides to stock purchasing.

“It is great for Myanmar people to learn about the stock market. It will bring new hope for our business sector,” business consultant Nwe Ni Soe told AFP at a recent training day.

Under the military, Myanmar was plunged into poverty and pummelled by banking crises, international sanctions and arbitrary economic policies that destroyed the once vibrant economy and saw ordinary people hoard savings in assets like gold.

The tide began turning under the outgoing reformist quasi-civilian government which took power in 2011.

A handful of foreign banks have slowly crept into the country, while a raft of new business and finance laws have begun to untangle a messy legal landscape.

The World Bank says the country could grow by as much as eight percent a year for the next five years, but says firms are struggling with access to finance.

Myanmar’s incoming government is faced with a raft of challenges as it looks to encourage investment and create jobs.

In the way is a weak kyat currency, decrepit infrastructure, patchy electricity and an urgent need to improve skills in a nation whose education system withered with neglect under the junta.

Solo trader

The YSX will initially launch with just a single firm, First Myanmar Investment run by Myanmar tycoon Serge Pun, and only be open to domestic investors.

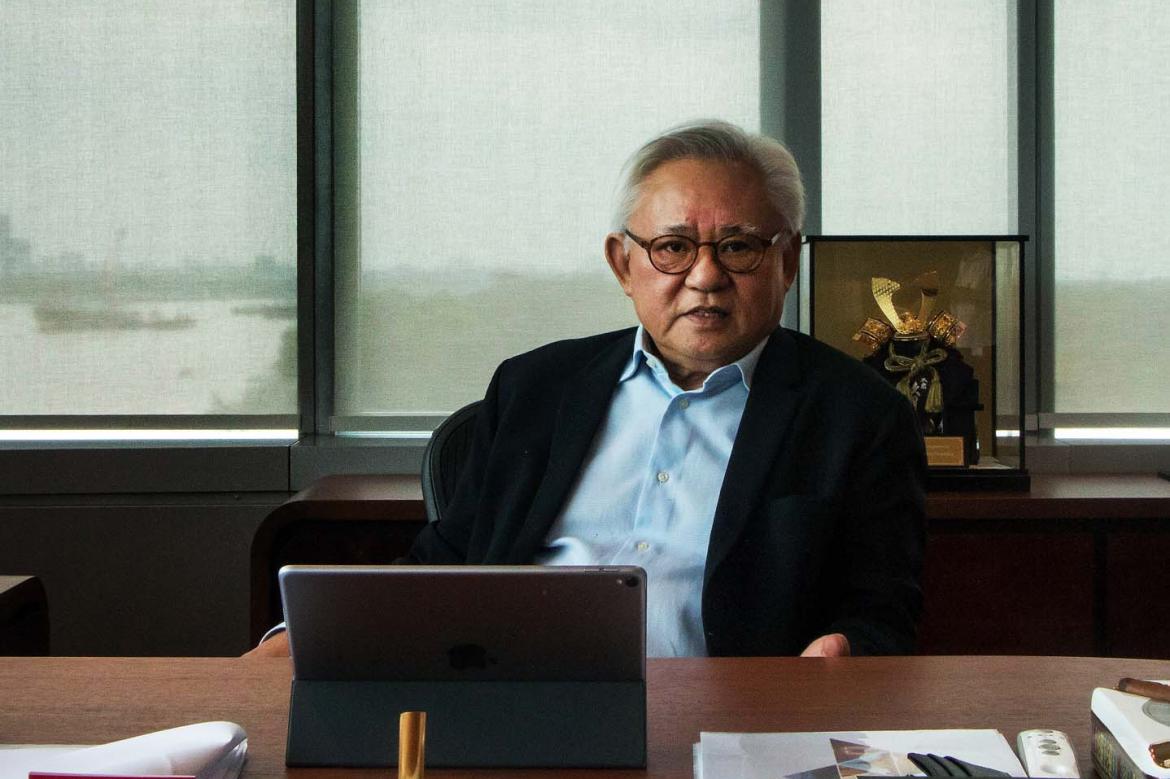

Tun Tun, FMI’s executive director and chief finance officer, said he hoped the bourse would provide a “healthy capital market for the benefits of both investors and businesses”, urging authorities to accelerate plans to allow foreign investment.

With its sister firm Yoma Strategic Holdings listed in Singapore and around 6,800 shareholders through an in-house system, FMI already has experience of stocktrading, a rarity in Myanmar.

Several other firms that have been approved to list, including the Japan-backed Thilawa Special Economic Zone, have yet to finalise their preparations.

Rajiv Biswas, Asia-Pacific chief economist, IHS Global Insight, said it would take time for YSX to overcome an array of hurdles, like building up enough stocks to trade, creating liquidity and putting in place strong governance standards.

“Relatively new stock exchanges need to build confidence among investors about the transparency of listed companies in their stock exchange filings, as well as setting tough regulatory standards to prevent acts such as insider trading or market manipulation,” he said.

But he added that the market could have a “crucial role to play” in the future for both government and companies to raise equity and debt for “funding their economic expansion plans”.

Investing in the future

The bourse has been decades in the making.

In 1996 Japanese firm Daiwa Securities and a state bank set up the Myanmar Securities Exchange Centre, but this allowed over-the-counter sales of shares in just two firms.

“We didn’t make much progress under the last junta regime,” said Thet Htun Oo, a senior bourse official.

A joint venture agreement was eventually signed in 2014, with Myanma Economic Bank owning a controlling 51 percent stake in YSX, with the remainder divided between Japanese partners.

It is now housed in a newly-renovated colonial-era building, replete with a gleaming trading bell, souvenir shop and cafe.

Officials are aiming to attract 30 to 50 firms in five years. Early investors are expected to be businesses and individuals, and Thet Htun Oo said they are “very eager”.

At its ceremonial opening in December, officials were stunned to see a crowd of people outside wanting to buy shares, some from as far away as Myanmar’s second largest city Mandalay.

That enthusiasm is on show at the YSX’s weekly classes.

“YSX is a chance for the future,” said business advisor Than Win at a recent training session.