Majors and captains are the headmasters at more than 20 cantonment schools that serve the children of Tatmadaw families.

By MRATT KYAW THU | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

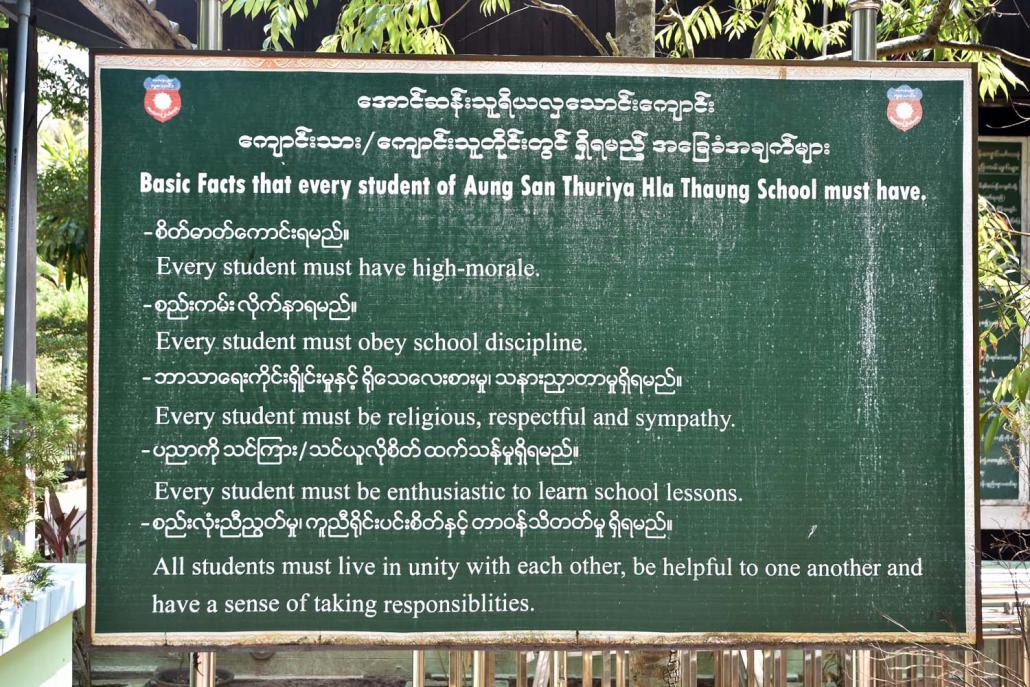

IT IS NOT widely known that throughout the country there are schools where the students gather regularly before class in their green and white uniforms to sing the National Anthem before a military officer.

The officer is their headmaster.

Ministry of Education reports indicate that there are more than 20 of these cantonment schools, which offer classes from first standard to matriculation. The schools are funded by the Department of Basic Education and teach the standard state curriculum, but are run by military officers and overseen by the Tatmadaw.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

Although it is difficult to determine exactly when the schools were launched or came under military administration, military and education sources say it was “probably” late in 1988, when the Tatmadaw seized power from the Ne Win regime and crushed the 8-8-88 national uprising.

There is at least one cantonment school in every state and region, though some have two, such as Rakhine State, with one at Ann Township, where Western Command has its headquarters, and another at Taungup.

Majors and captains

Unlike Basic Education schools, which are run by civilian headmasters or headmistresses appointed by the Ministry of Education, the headmasters of cantonment schools are majors or captains appointed by the Tatmadaw’s Directorate of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare.

Military sources say the minimum educational qualification required to be headmaster of a cantonment school is a post-graduate degree. They must also have a Bachelor of Education.

“I graduated with a normal Bachelor [of Education] degree, so even if I wanted to be a headmaster at a cantonment school, I can’t. You need to at least have a master’s degree,” said one 30-year-old Tatmadaw officer, who is in a field command role. “[For a Tatmadaw officer], there are relatively few opportunities to work in education.”

U Toe, the secretary of Aung San Thuriya Hla Thaung and a volunteer teacher. He says the school’s high academic achievement is because of the discipline instilled by its military officer headmaster. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

But, in practice, the educational qualifications for military headmasters are not always insisted upon.

The headmaster at Aung San Thuriya Hla Thaung cantonment school in Yangon’s Mingaladon Township was appointed nearly 12 years ago with a Bachelor of Science (Zoology) degree, said U Toe, who is the school’s secretary and a volunteer teacher there. While serving as principal, the officer, a major, completed a distance degree in education, but doesn’t hold a postgraduate degree.

“Our major was previously from a very small security unit at the Namtu Bawdwin mine. After that he got promoted directly to be headmaster of this school,” said U Toe.

The major declined to be interviewed and asked that Frontier instead interview U Toe.

All cantonment school headmasters wear the Tatmadaw’s green uniform and are addressed by pupils according to their rank, either bo hmu (major) or bo gyi (captain).

Steve Tickner | Frontier

The military principals have to provide progress reports on their schools three times a year at military conferences.

“We don’t need to report to the Ministry of Education, but to the Directorate of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare,” said U Toe.

About 80 percent of their students are from military families and the rest are the children of public servants. The enrolment system gives first priority to children from families living in the cantonment, followed by children from serving military families living in that particular state or region.

Then, in descending order of priority, are children of serving military families from other states and regions, children of retired soldiers living in the cantonment area, and finally children of retired soldiers living in that particular state or region.

The enrolment process differs from that of Basic Education schools, at which admissions are decided by a headmaster and board of teachers. For cantonment schools, five military personnel – not including the headmaster, who is not involved – compile enrolment lists that are submitted to the head of the Directorate of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare in Nay Pyi Taw for scrutiny.

A spokesperson for the Department of Basic Education, U Ko Lay Win, said cantonment schools have their own management system “but we receive their enrolment lists”.

Students at the Aung San Thuriya Hla Thaung cantonment school in Yangon’s Mingaladon Township. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Cantonment schools once had civilian headmasters and Ko Lay Win said the change to using military officers as principals was made to avoid problems involving “protocol”.

“It’s better if the military runs the schools attended by the children of military families. The management will also be better,” he said. “A civilian might not understand the protocols followed by military families and that would be problematic.”

U Toe agreed, adding that civilian headmasters only have to engage with the civilian parents of their pupils, “but at cantonment schools the headmaster has to engage with parents who are from the military”.

Headmasters of cantonment schools not only have to negotiate military hierarchy and protocol when dealing with parents, but also teachers.

An unofficial rule for Tatmadaw officers is that their wife must be at least a university graduate. Teaching, in particular, is considered a respectable and dignified career for the wife of an officer, and as a result many wives end up teaching at cantonment schools.

“Soldiers wives who work as teachers are regarded as being special and receive privileged treatment at both cantonment and government schools,” said one high school teacher, who requested anonymity.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

Five teachers – two at cantonment schools and three at state schools – told Frontier that teachers married to soldiers are given preferential treatment if they want to transfer to schools in more desirable locations.

Usually, a teacher must be prepared to spend at least two years at a school before they can request a transfer. However, government teachers said this does not apply to soldiers’ wives who work as teachers, and they often seek transfers if they don’t like a school’s location.

“In my school, it’s like a public rest-house; soldiers’ wives come and go every month,” said a 42-year-old teacher at a high school in Hlaing Tharyar Township, which is considered an undesirable place to teach.

However, Ko Lay Win denied that it was easy for soldiers’ wives who work as teachers to arrange transfers.

“This doesn’t happen anymore,” he said. “I would say this has not happened since the National League for Democracy government took office in 2016.”

Essays and poems written by students to mark Martyrs’ Day are displayed at the Aung San Thuriya Hla Thaung school. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Many civilian teachers at cantonment schools told Frontier that the military headmasters found it hard to engage with pupils, and suggested that this was because of the way life in the Tatmadaw had moulded them.

But U Toe said he enjoyed working for the military as a teacher and suggested that Basic Education schools would be more effective if they were run like cantonment schools.

He said cantonment schools more closely followed state-imposed rules and regulations regarding education, and this was reflected in their good performance on matriculation exams. Most years, he said, Aung San Thuriya Hla Thaung has among the best results in the country – sometimes it even tops the list.

“Civilian headmasters are really flexible and soft and they let things go; the headmasters of the cantonment schools are different because they are under the Ministry of Defence,” U Toe said. “The military is one blood, one voice and one order, so our cantonment schools are more disciplined.”