The military’s admission of involvement in the Inn Din massacre was made to pre-empt the release of the Reuters report, and after its own investigation had claimed that no such killings took place.

LAST WEEK’S explosive Reuters investigation into the killings of 10 Rohingya at Inn Din in northern Rakhine State in September made for grim reading.

In what is one of the best, most detailed reports on the crisis, the Reuters team – including journalists Ko Wa Lone and Ko Kyaw Soe Oo who were arrested in December while researching the story and remain in jail – documented how government troops and Buddhist villagers carried out the killings and buried the victims in a single grave.

Few who have seen it will forget the haunting photograph of the kneeling men surrounded by security forces shortly before their death. In this case, the “picture tells a thousand words” cliché rang true. But the text was just as powerful; a 4,500-word indictment of the authorities’ brazen denials that its forces have been responsible for systematic human rights abuses.

Of course, the military has already admitted that its forces, together with Buddhist villagers, killed the 10 men. It did this to pre-empt the release of the Reuters report, and after its own investigation had claimed that no such killings took place.

But it also claimed it was a crime borne of hatred and necessity, and one without premeditation. The Reuters report offers credible, compelling evidence to the contrary – not least the testimonies of those involved.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

It once again highlights the need for an independent investigation team to be given access to the region and examine what occurred at Inn Din, as well as other communities in northern Rakhine State where massacres are alleged to have occurred.

A crucial revelation from the Reuters article, corroborated by multiple sources, is that security forces were instructed by their superiors to “go and clear” the Muslim villages.

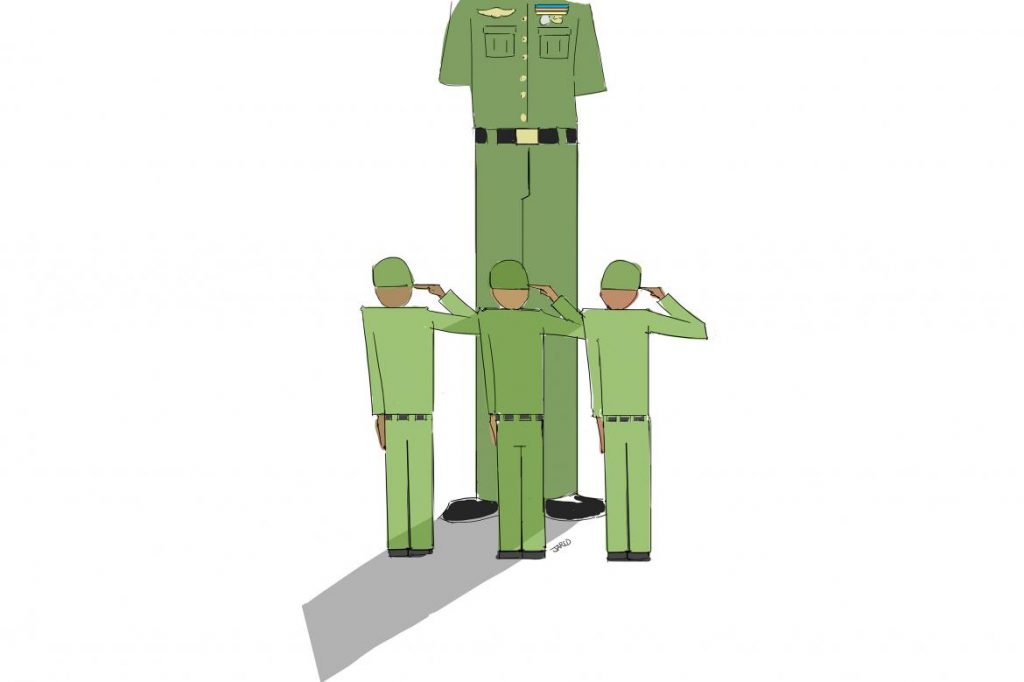

To be credible, any investigation must examine these instructions and establish where they originated. The culture of punishing low-level officers while those up the chain enjoy impunity must not be repeated.

Any investigation conducted by the Tatmadaw alone is not credible. The November statement clearing its troops of any wrongdoing is the clearest evidence of this.

But instead of a credible investigation, the military appears to have targeted those involved – and not only the two journalists, whom senior National League for Democracy official U Win Htein said were likely set up by the security forces.

The day after the Reuters report was published, U Tin Myint, permanent secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, told Frontier that the administrator of Inn Din, U Maung Thein Chay, was also under investigation. Maung Thein Chay, who is a Rakhine Buddhist, was quoted in the Reuters article as saying that soldiers and paramilitaries dressed in civilian clothing to blend in with local residents.

The message is clear: don’t speak out. Don’t contradict the official line. Don’t tell the truth. Undoubtedly the military will be working hard to identify those within its own ranks who spoke to the journalists, too.

At the same time, journalists and human rights groups continue to monitor the situation closely, particularly at the Bangladesh border where access is less restricted. It seems reasonable to expect that more stories like the Reuters report will continue to emerge in the months and years ahead.

The military and government are at a crossroads. They can continue to hold steadfast to their denials and conduct any number of farcical investigations, and in doing so they will be ostracised by Western governments, and pushed back into the arms of China and other countries who prioritise their own economic interests over human rights. This is profoundly dangerous: The Rakhine State crisis is already reshaping Myanmar’s international relationships in ways that will have serious long-term implications for the country and its democratisation process.

But the damage is not completely irreversible. The past cannot be undone, but the Myanmar authorities have the opportunity to allow in independent investigators, and to establish a refugee repatriation programme that allows returnees to do so voluntarily and with dignity. They can ensure the safety and security of all people in Rakhine State. And they can address the underlying causes of the violence by implementing the recommendations made by the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State in its final report last year.

It largely comes down to what sort of country Myanmar wants to be seen as: Does it want to be one that oversaw a massive humanitarian disaster, a disaster borne of bloodshed and fire? Or one that resolved a long-standing communal crisis for the benefit of all?

This editorial appears in the February 15 edition of Frontier.