Observer groups judge the November 3 polls as largely transparent and fair but decry the lack of electoral reform.

By MRATT KYAW THU, HEIN KO SOE, KYAW LIN HTOON and BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

ON BY-ELECTION day in Yangon’s Tarmwe Township, a crowd waited through the morning to see President U Win Myint vote for the parliamentary seat he used to represent.

The by-election in Tarmwe, which took place alongside 12 others across Myanmar on November 3, was held because Win Myint’s elevation to the presidency in March this year had left the Pyithu Hluttaw seat empty. The constitution stipulates that executive office-holders, from presidents to ministers, must relinquish any parliamentary seats that they hold.

Win Myint came and went with his wife in the early afternoon, accepting petitions from citizens via party functionaries. Yet, despite the excitement his visit generated, only a third of registered voters turned up to vote in Tarmwe.

National League for Democracy candidate U Toe Win, who went on to claim Tarmwe with a convincing 85 percent of the vote, told Frontier, “I think I won this by-election because of the strong support and benevolence of the people. I see this election as free and fair, and I would like to thank my voters very much.”

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Domestic and international observer groups largely agreed with this assessment of the process. Hundreds of thousands of voters cast ballots in by-elections certified as largely transparent and fair. However, observer groups noted the absence of electoral reform since the 2015 general election, and pinpointed a lack of voter education, which may have contributed to poor turnout.

This lack of reform meant that similar flaws in the electoral system that fed distrust and allegations of foul play during the 2015 election – in particular, an advance voting process that follows convoluted rules and fundamentally lacks transparency – resurfaced on a small scale during the November 3 polls. With only two years to go before the next general election in 2020, the window for electoral reform is narrowing fast, say observers.

Surprise wins

The results of the polls, for five seats in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (national legislature) and eight in state and regional assemblies – all but two of which were made empty because their incumbents died while in office – saw the ruling NLD lose four of the 11 seats that it previously held.

Myanmar’s ruling party successfully defended the Pyithu Hluttaw seats of Tarmwe in Yangon, Myingyan in Mandalay Region and Kanpetlet in Chin State; Oktwin-1 in the Bago Region parliament; Minbu-2 in the Magway Region assembly; and Thabeikkyin-1 and the Shan ethnic affairs minister’s seat in the Mandalay Region parliament.

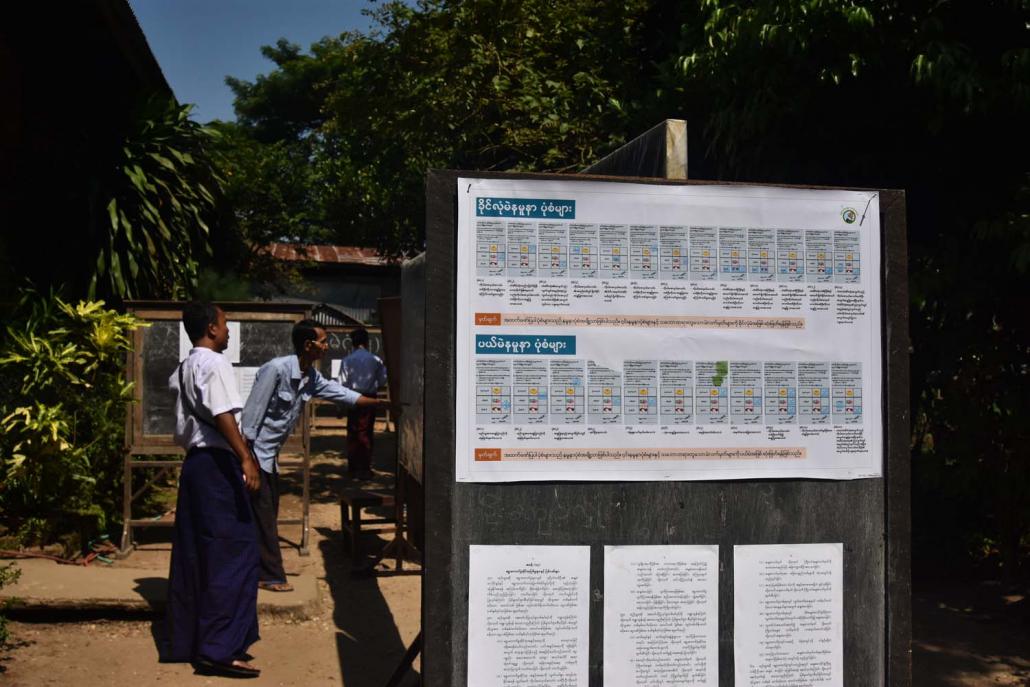

Voters check names their names on the voter list before entering a polling station in Tarmwe. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

There were three surprise wins for candidates from the NLD’s military-backed adversary, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, which took the Kachin-2 seat in the Amyotha Hluttaw, Tamu-2 in the Sagaing Region assembly, and Seikkan-2 in the Yangon Region parliament.

However, it was a day of mixed success for ethnic parties. While the Chin League for Democracy took the seat of Matupi-1 in the Chin State parliament from the NLD, both the Chin National Democratic Party and the Chin Progressive Party failed in their attempts to win Kanpetlet. Meanwhile, the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy held the Pyithu Hluttaw seat of Laikha in Shan State.

In Kachin-2, encompassing the Kachin State capital Myitkyina, four ethnic Kachin parties had shelved their rivalry to unite behind Kachin Democratic Party candidate Gum Grawng Awng Hkam. He beat the NLD, which previously held the seat, but came a close second to the USDP candidate, U Hsi Hu Dwe.

In the race for the Rathedaung-2 seat in the Rakhine State parliament, a fracturing of the Rakhine nationalist movement had produced considerable excitement among many voters in the township. This election was largely limited to the Rakhine Buddhist community; many of Rathedaung’s Rohingya Muslim residents had fled brutal army reprisals that followed attacks on security posts by Rohingya militants last year, and those who remain are mostly disenfranchised because they lack citizenship.

In Rathedaung, election fever was focused on independent candidate U Tin Maung Win, the son of Rakhine nationalist leader Dr Aye Maung, who now sits in jail and is being prosecuted for alleged high treason and sedition. Tin Maung Win went on to win 80 percent of the vote, beating candidates from the party his father used to lead, the Arakan National Party, and the Arakan League for Democracy, which split from the ANP last year. Turnout was comparatively high at 58 percent.

Late ballots?

More than 1 million people were eligible to vote on November 3, but turnout was low in most constituencies. Election observation groups noted a minimal level of voter education relative to the civil society-led rollouts during the 2015 general election and the 2017 by-elections, which involved 19 seats. At press time, the Union Election Commission had not released figures for the overall turnout.

The polls were largely sedate, provoking few incidents or disputes besides in Myitkyina, where seemingly universal voting by soldiers and their adult family members in the city’s large military cantonments delivered a win to the USDP in the Kachin-2 race. This was enabled by a low turnout among civilians in Myiktyina, who otherwise would have greatly outnumbered military voters.

A domestic observer group, the People’s Alliance for Credible Elections (PACE), reported that advance votes cast mostly by soldiers serving outside the constituency were received at the tabulation centre after the 4pm cut-off time on election day in Myitkyina, but were counted in breach of electoral rules.

Electoral staff deliver counted ballots at the Tarmwe Township tabulation centre on the evening of November 3. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

However, none of the other observer groups reported this apparent irregularity, despite also fielding observers in Myitkyina. NLD candidate Daw Yan Khaung told Frontier that the out-of-constituency advance ballots were not received late, and that election staff counted them in full view of candidates and observers. Myitkyina Township election sub-commission chairman U Maung Maung told Frontier that PACE had got the story “absolutely wrong” and the several thousand out-of-constituency advance votes had been received by noon.

Though the thousands of advance votes for Kachin-2, cast overwhelmingly for the USDP candidate, didn’t swing the election, the runner-up, the KDP’s Gum Grawng Awng Hkam, is still considering whether to file a challenge to the result that would trigger a hearing before a tribunal convened by the UEC.

The results of the by-elections also indicated the stark inequality between constituencies in terms of the numbers of voters that they contain. The USDP’s U Nay Myo Aung won Seikkan-2 in the Yangon Region parliament with only 512 votes to the NLD candidate’s 356, in a constituency of only around 1,500 voters. A voter in Seikkan Township wields a ballot that’s around 50 times more powerful than a vote in Tarmwe Township for a seat in the same parliament.

The ratio between Myanmar’s smallest constituency, on the Coco Islands off the coast of Yangon Region, and the largest, encompassing Yangon’s Hlaing Tharyar Township, is around 400 to one.

A missed opportunity

For the by-elections, the election commission accredited 1,173 domestic observers and 256 international observers, most of who were deputed by 22 foreign embassies.

Domestic observer groups PACE and Election Education and Observation Partners (EEOP) and international group the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) commended the credible and peaceful conduct of the by-elections. Besides PACE’s advance voting allegation, the groups reported only minor procedural errors that did not affect the overall integrity of the process, and which they attributed to inadequate guidelines and training for polling staff.

EEOP’s 149 observers, stationed across all constituencies on election day, rated the process as “well conducted” in 95 percent of all polling stations observed. However, the group noted “inadequate” voter education in the run up to the elections, which was mostly undertaken by candidates and parties in the absence of civil society and government efforts.

A voter casts a ballot in a polling station in Tarnwe. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

ANFREL, which deployed 11 observers, noted a failure to undertake reforms recommended in observer reports from the 2015 general election and the 2017 by-elections. It said in its post-election statement, “the 2018 by-elections fail to deliver any substantial improvement. Such stagnation feels like a missed opportunity in a fragile democratic context.”

PACE, which deployed 579 observers, agreed with ANFREL in its post-election statement: “there are no major improvements in the election administration compared with the 2017 by-elections.”

EEOP, in its report, pointed out a largely overlooked regression. Only seven of the 69 candidates in the by-elections were women. This proportion, of around 10 percent, is down from 17 percent in the 2017 by-elections.

PACE highlighted a lack of facilities for voters with disabilities, with 54 percent of stations observed not having a booth set up for voters using wheelchairs.

A need to pick up the pace

Electoral experts who spoke with Frontier said key shortcomings of Myanmar’s electoral process included an error-prone and insufficiently audited voter list, which continues to inspire distrust from political parties, and skeletal campaign finance regulations, which depend on self-declaration and allow a considerable loophole between “candidate” and “party” spending.

Most controversial, however, is the out-of-constituency advance voting process, which mostly applies to army soldiers serving in forward bases or attending training academies – and which almost determined the result in the Myitkyina by-election. These votes are cast beyond the administration of the UEC, which merely sends off the ballots and later receives them for counting, and beyond the scrutiny of observers and candidates.

Moreover, any challenges to election results are referred to a tribunal made up of UEC commissioners, whose decisions are final, leaving aggrieved candidates with no independent legal recourse. These commissioners are appointed by the president, which critics say limits the UEC’s independence.

A voter displays an inked finger on November 3 in Tarmwe. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

Notwithstanding these broader reform issues, there are also signs that the UEC may be becoming more opaque.

PACE director Sai Ye Kyaw Swar Myint told Frontier that the UEC had undertaken the 2017 by-elections with more transparency, for instance by publishing an electoral calendar that dated key aspects of the electoral process, including the public display of the voter list, candidate registration and observer accreditation, well in advance. This year, no calendar was made public, for reasons that remain unclear.

He remarked that the only electoral reform of note since 2015 has been the draft merger of the three separate electoral laws for the upper and for the lower houses of the Union parliament and for state and regional parliaments, which were almost identical to begin with.

Sai Ye Kyaw Swar Myint said that the UEC commissioners appointed by the new NLD government in early 2016 had begun with a burst of activity, holding two national round-table conferences on electoral reform with civil society taking part. In the years since, however, enthusiasm seems to have waned. “There’s no consultation process at the moment,” the PACE director said.

Mr Greg Kehailia, Myanmar country director for the US-based Carter Center, which observed the 2015 election and provided technical support for EEOP in its observation of the by-elections, told Frontier that, despite appearances, “the UEC takes seriously the recommendations of electoral observation missions”.

“Our understanding is that there is an ongoing dialogue between the parliament and the UEC about a possible revision of the electoral laws; but there is not much information available about the scope of the envisioned electoral reform,” he said.

Kehailia said that, though the window was tight and electoral reform tends to take a while, “There is enough time to address a lot of issues between the November 2018 by-elections and November 2020 general elections. That will require a comprehensive, well-coordinated and inclusive reform plan … built on a systematic dialogue with civil society and political parties.”

“The UEC and the Parliament still have time to make a critical difference. Given the work required to implement some key recommendations, the reform process has to pick up the pace now,” he said.