The Constitutional Tribunal has not recovered from a dispute in 2012 that prompted the mass resignation of its members but the NLD could undertake a range of measures to rebuild its powers and contribute to restoring judicial independence.

By HTIN KYAW AYE | FRONTIER

BAD HABITS can be formed easily. So it is in Myanmar’s nascent democracy, which is fast assuming some illiberal characteristics. In a normal democracy, the influence of rivalry for power over reciprocal accountability among different institutions is limited, but rather their independence keeps the political order by limiting the domination from one player. In Myanmar, checks and balances are widely becoming a term to portray competition between key power players.

Most commentators note that although the 2015 elections produced a popularly elected government, the Tatmadaw – by virtue of the 2008 Constitution – retains considerable political influence through its direct appointment of 25 percent of MPs, its control of three key ministries (Defence, Home Affairs and Border Affairs) and a veto over constitutional change.

Hence, Myanmar’s military has only barely relinquished its power and control. There’s also the implicit threat that any efforts to further entrench democracy can be blocked, including by a return to military rule.

But still, it’s worth asking the question: Some 16 months after assuming democratic power, what has the NLD done to entrench democracy? Far too little, it seems.

One area it has failed to make progress is the Constitutional Tribunal. Myanmar’s top courts have long experienced political influence and efforts to undermine judicial independence. The 2008 Constitution, ratified at a national referendum in the weeks following Cyclone Nargis, which killed nearly 140,000 people, provides for significant illiberalism. For example, it allows the ruling government to directly appoint the tribunal, which has responsibility for interpreting the country’s constitution. Although the Supreme Court officially is the country’s highest court, the Constitutional Tribunal also has very significant powers that could be subject to political machinations.

The legacy of a power struggle

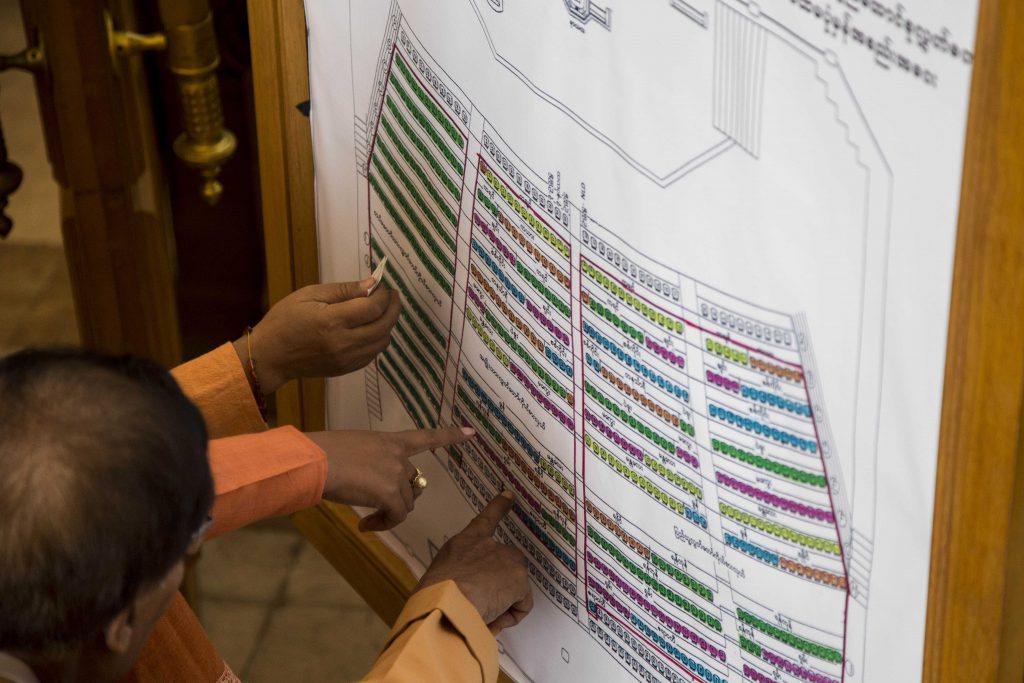

In 2012 the Constitutional Tribunal was tasked with defining what is meant by a “Union-level organisation”. In a February 2012 ruling, the tribunal determined that parliamentary committees are not “union-level organisations”. This decision outraged many parliamentarians, who interpreted it as showing disrespect for them and undermining their work. They responded by moving to impeach the members of the tribunal, but just before parliament passed the articles of impeachment tribunal members resigned en masse. This incident highlighted the inherent flaws – or political calculations – in the 2008 Constitution.

This dispute occurred against a backdrop of competition within the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party that pitted the parliament under Speaker Thura U Shwe Mann against President U Thein Sein’s administration. This conflict was driven by personal rivalry between Shwe Mann and Thein Sein as well as the parliament’s efforts to shrug off perceptions that it was a “rubber stamp” for the government.

Following the resignation of the members of the Constitutional Tribunal, parliament wasted no time in approving significant changes to the Constitutional Tribunal Law. These changes removed the president’s power to nominate the chair of the tribunal, and limited the tribunal’s decision-making power to the judicial realm only. A year later, however, parliament reinstated the scope of the tribunal’s decision-making powers so that its decisions must be respected through all parts of the government.

shwe_mann.jpg

title=

But significant damage had already been done, at least in terms of democratic principles and processes. Since 2012, tribunal members are answerable to those who nominate them – that is, the president and the speakers of the two houses of parliament. The term “report to”, as mentioned in the 2008 Constitution, illustrates this clear hierarchical relationship. This is the antithesis of judicial independence. The tribunal has never really recovered from its political defeat in 2012. When two subsequent changes to the tribunal law were considered by parliament, in 2014 and 2015, tribunal members contributed little to the discussion.

The tribunal is tasked with interpreting the constitutional clauses, resolving constitutional disputes between institutions, and deciding on the constitutionality of laws passed by the legislative bodies and measures taken by the executive bodies, both national and regional. Since its establishment in 2011, the tribunal has considered 12 cases of which four were rejected. These rejections came after the controversy with the parliament in 2012,.

As indicated above, the weaknesses in Myanmar democracy mostly stem from the 2008 Constitution. The constitution, which was never properly debated before being enacted, enables the ruling party to influence the country’s highest constitutional court by appointing all tribunal members upon assuming office. In addition, the term of the Constitutional Tribunal is roughly concurrent with that of both the president and parliament, preventing effective judicial independence or oversight.

The 2015 amendment to the tribunal law allows members to campaign for election to parliament while still serving on the tribunal, thus politicising their role. They are also allowed to remain party members, although they cannot participate in party activities and if they become MPs they can no longer sit on the Constitutional Tribunal.

Building Myanmar’s democracy

There are no panaceas to bringing about more robust democracy in Myanmar. That said, the problems with the Constitutional Tribunal could be addressed if they were considered as institutional rather than political. Firstly, the term of the tribunal could be changed, and not tied to presidential or parliamentary terms of office. Giving members of a supposedly independent judicial institution the same term of office as those with the power to appoint them is clearly not a good idea. The law could also be changed to break the influence of the government and parliament over the tribunal’s actions. Although it is necessary to have some institutional checks and balances, the current “reporting to” situation is untenable. A simple majority vote in parliament could introduce these changes to the tribunal law.

While the military maintains a veto over constitutional change through its 25 percent parliamentary bloc, the NLD could still consider submitting an amendment bill. The party would only need the support of 20 percent of MPs in order to propose an amendment. It could put forward changes to the clause to adjust the tribunal’s term of office, for example. It will then need a “super majority” of 75 percent in the parliament, but it doesn’t require a referendum for that change. An amendment bill would enable the NLD to “test the waters” of constitutional reform in areas where the Tatmadaw has no clear vested interest.

While the military is known to oppose some constitutional changes, there are no obvious reasons why it would object to ending political influence over the court tasked with interpreting the constitution, particularly when the Tatmadaw’s platform appears to focus on safeguarding both the constitution and Myanmar’s overall sovereignty and integrity.

However, more than a year after assuming office, there are few signs from the National League for Democracy that it is interested in address issues related to the Constitutional Tribunal. Indeed, the party may not see it as a problem in need of fixing; in 2015, it supported amendments to the constitution – subsequently blocked by the military – that would have diluted the tribunal’s powers.

However, NLD leaders have regularly stated that establishing rule of law and undertaking judicial reform are priorities, and its election manifesto promised the party would undertake a range of measures “in order to establish a fair and unbiased judicial system”. It would certainly be in the party’s interests to mend the broken pieces of Myanmar’s judicial independence, including the Constitutional Tribunal. But change will only occur – or at least be attempted – when NLD begins to see opportunities instead of insoluble problems.