Popular informal savings and lending schemes have become a vehicle for scammers who lure in victims with the promise of fast, high returns.

By KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

WHEN HER husband opened a shop selling glass and aluminium products in Bago city two years ago, Ma Eithinzar Kyaw was a housewife. But she wanted more from life. A graduate with a major in economics, she had worked at a bank branch in Bago before marrying.

“I became dependent after I married six years ago,” she told Frontier in an interview at a shophouse she rents in the regional capital. When Frontier visited her on June 30, Eithinzar Kyaw was taking care of her two children and serving customers in the shop.

“The business is doing well. We want to expand but getting a loan from a bank is almost impossible for us,” she said.

To help raise the capital needed to expand the business, Eithinzar Kyaw began selling clothes and other products online in 2016. However, the earnings from these two sources were not enough to raise the money needed to expand the shop, Eithinzar Kyaw said.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“The price of glass and aluminium raw materials always goes down in the rainy season; our idea is to stock up during the rainy season and sell later when the price goes up.”

She started looking for another way to make money.

A traditional way to save

Eithinzar Kyaw had friends who claimed to be reaping handsome profits from an online version of a traditional Myanmar method of informal saving and lending. It involves groups of friends, colleagues or neighbours who form a collective into which they each agree to deposit a predetermined amount at regular intervals.

For example, a group of 10 people each agree to deposit K10,000 each month into a common fund for 10 months. Each participant takes turns, month by month, to have K100,000 at their disposal. The organiser, the one responsible for collecting the money from the participants – known as the mae daing in Burmese – usually takes the first share. The order for other participants is decided by drawing lots.

It is a popular way of both saving money and raising funds, but it relies on each participant being trustworthy. If one member of a group defaults on their obligation, the scheme collapses.

High mobile phone penetration in Myanmar has spawned the emergence of similar fund-raising schemes among social media users, who transfer contributions to their group’s fund through banks or mobile money payments. And where traditionally the savings pools were small amounts of money, the online versions have begun dealing with much larger sums – in some cases, hundreds of millions of kyat.

Typically, if a person urgently needs their share of the money early, they can request to swap with another participant by explaining their financial difficulties. But when the amount of money involved becomes large, it’s no longer easy to jump the queue to draw down the saved money.

A person who needs the money urgently can instead raise the funds by selling their share to a third party at a discount. For example, a participant who still has to wait another two weeks to access K5 million could sell their share now for K4.5 million. The person who buys from them can make a good profit in a very short period of time.

In this way, an online – and completely unregulated – market of selling positions in these savings programmes has developed. Many are offering returns that are too good to be true. A common proposition would be to buy a savings stake of, say, K10 million for K8 million, with a payout in a week.

The premise is that the person selling the stake needs the money now. But those taking part seem to have ignored the implausibility of the scenario. Who would take a 20 percent loss on their investment just to gain access to their money a week earlier? The chances of there being a real person on the other end of this deal are slim.

At first, though, the returns offered are small. The victims come to trust the scheme and are encouraged to invest ever-larger sums. Inevitably, many of those seeking a large, quick profit have lost their savings – and those of their friends and relatives.

‘Greed made me blind and stupid’

At first Eithinzar Kyaw didn’t trust these online savings schemes, she said. “But then I found out some of my friends had made a high profit from buying these savings online.”

Eithinzar Kyaw joined the scheme at the encouragement of someone she regarded as a personal friend, Ma Hnin Wai Thi, also known as Ma Thae Thae. In less than a month she would end up losing K80 million – half of it her money, the rest invested by friends and family.

Ma Eithinzar Kyaw invested in a traditional savings and loan scheme in order to create some capital to expand her family business, but instead ended up losing K40 million. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

“I believed her because we used to help each other with our online shopping businesses,” Eithinzar Kyaw said.

She sent a first contribution of K450,000 to Hnin Wai Thi on April 1 and received a return of K500,000 on April 17. Impressed, she continued contributing and making money. Finally, she shared her profitable experience with family members and other friends.

“As you know, when Myanmar people encounter something that benefits them they like to share it with people they love,” she said.

Eithinzar Kyaw contributed three times and realised a profit three times, which she re-invested in contributions.

By the end of April, the total amount she had invested, including funds from relatives and friends, totalled tens of millions of kyat.

Eithinzar Kyaw said that on May 11, Hnin Wai Thi failed to return a payment as scheduled. The amount was K28 million. Eithinzar Kyaw was asked to wait to until May 12.

“[Hnin Wai Thi] told me that her mae daing had delayed the payment. She said she was going to solve the problem by getting a loan from someone who was using her father’s house as collateral. I pawned my gold jewellery to repay my friends,” she said.

Eithinzar Kyaw said Hnin Wai Thi deactivated her Facebook account on May 12 and stopped returning her phone calls.

“I was still thinking she would not do this to me but I was wrong,” she said.

Eithinzar Kyaw opened a case against Hnin Wai Thi at Bago police station on June 1, partly because she was under pressure from friends who wanted their money back.

“I didn’t really want to do this, but I had no choice. Otherwise, I also have to face accusations myself,” she said.

“As I am partially responsible for their loss, I promised my friends that I will gradually pay back 30 percent of their investment,” she said, adding that some friends had taken merchandise from her glass and aluminium shop as repayment.

Eithinzar Kyaw said she presented the police with documents showing that she transferred about K80 million to Hnin Wai Thi through bank and Wave Money transfers, of which K40 million was her own funds.

Asked why she had invested in such a risky business, Eithinzar Kyaw said she was motivated by greed. She also acknowledged being gullible.

“[Hnin Wai Thi] told me that these saving businesses came from jewellery traders who are doing money laundering,” she said. “I know little about money laundering and what she told me seemed to make sense. But the main factor was greed, which made me blind and stupid.”

Eithinzar Kyaw is not alone. On May 30, another woman in Bago reportedly opened a case against Hnin Wai Thi, alleging she had lost K5.7 million. Since then, dozens more charges alleging cheating have also been filed against Hnin Wai Thi at Letpadan in Bago Region and in South Okkalapa, North Okkalapa and Thaketa townships in Yangon Region.

Hnin Wai Thi was taken to police stations in Yangon for processing before being transferred to Letpadan. She spent two nights in custody before being released on bail.

‘Everything you see here has already been pawned’

Frontier interviewed Hnin Wai Thi at her parent’s two-storey house in Bago on June 30. She says 55 people have filed cases against her in an attempt to claw back almost K900 million they invested and lost.

“Honestly, I do want to pay back their money, but I have nothing,” she said, indicating her father’s house and Toyota TownAce.

Hnin Wai Thi said she had previously run an online business selling clothes and jewellery. She became involved in the online buying and selling of stakes in the informal savings and lending schemes in February.

“I started browsing the internet on my phone in 2013 and discovered there were many opportunities for business, so I started learning the new ways of doing business online,” she said.

Hnin Wai Thi said her family had a regular income from her online shop as well as the sales from their shampoo business, but it was not enough to realise her dream of owning her own home.

“We have been staying in my father’s house but we want to have our own house. When I learned that some online friends were making money from buying and selling savings, I thought it was an opportunity to make enough money to have my own home,” she said.

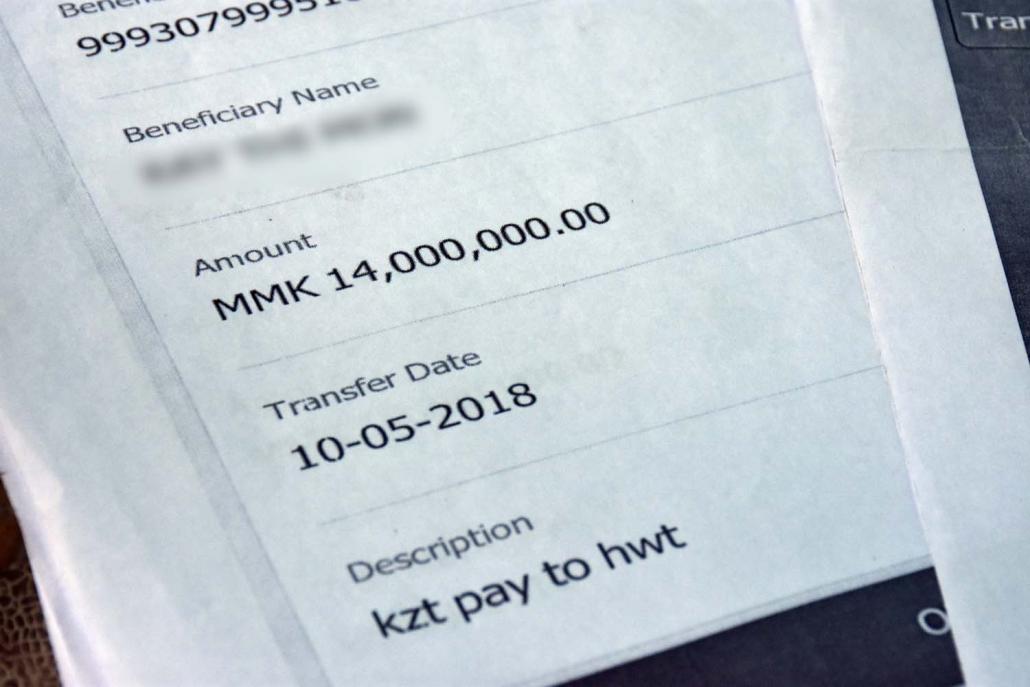

A transaction record showing a transfer of K14 million. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

The first four times Hnin Wai Thi invested in an online savings scheme, she received the promised returns. She then introduced the scheme to relatives and friends and in two months had become the conduit for an investment totalling K1 billion.

“I mainly purchased savings from three friends,” she said, naming three women. She had met these “friends” online, but never in person.

Hnin Wai Thi said the first time she and her relatives and friends failed to receive the promised return was in April. The amount involved was a K10 million allocation from a savings scheme.

“We bought it on April 10 with K8 million from [one of the three women]. The return was due on April 25 but she delayed again and again, saying she was also waiting for her mae daing,” Hnin Wai Thi said.

Overwhelmed by angry complaints from friends over the delay, Hnin Wai Thi went into hiding at an address in Bago for a week. When she returned to her father’s house on May 25, there was a crowd of about 50 people outside.

The police were called and Hnin Wai Thi was taken to Bago Myoma police station to be charged before being transferred and charged at the police stations in Letpadan and the three Yangon townships.

Hnin Wai Thi said she is considering filing a case against one of the three women, alleging that she transferred about K1 billion to her.

“As my friends have sued me for alleged cheating, I also have to sue her,” she said.

Hnin Wai Thi said she was unsure if the other woman was a cheat.

“I am a victim. I lost about K200 million [of my own money] over four months. But my friends think I am a scammer. I am not sure if [the other woman] has faced a similar situation,” she said.

Frontier received an initially cautious welcome during a visit to Hnin Wai Thi’s family home in Bago on June 30.

“We always keep the gate closed since we had a crowd outside the house on May 25,” said Daw Hla Hla, Hnin Wai Thi’s mother.

Hla Hla said it was only when the crowds arrived that she learned about her daughter’s involvement in the online money business.

“We thought she was doing good, but realised on May 25 that she had pawned the house and the car without our knowledge,” Hla Hla said.

“We were shocked because we saved all our lives for the house and car. But as parents we have to do our best to protect her.”

Ma Hnin Wai Thi shows a photo of the person she alleges she transferred the money to. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

This protection includes taking legal action: Hla Hla has opened a case at Bago Myoma police station against a Bago freelance journalist whom she alleges trespassed and made threats when he entered the family property on May 27.

She is also saving screenshots of some Facebook posts as evidence for charges she may seek under section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law.

No laughing matter

A raft of other cases of alleged cheating through savings programmes have also emerged in recent months. In the most high profile case, the daughter of a famous comedian, Dain Daung, was accused of organising one scheme in which investors lost money.

A lawyer acting on behalf of Nay Pyi Taw resident Ma May Thu, 24, issued a notice in state-run newspapers on May 7 warning Myat Noe Oo, better known as Dain Po Po Daung, to return K29 million that May Thu said she transferred to her between April 27 and May 1. Failure to return the money would result in legal action, it warned.

“When I first contacted her [Myat Noe Oo] in April, she told me that she will take responsibility if something goes wrong,” May Thu told Frontier on June 13. “And she said if she couldn’t handle it, her father would help her.”

But she said when she contacted the family after the first payment failed to arrive, Dain Daung, whose real name is U Tin Htay, answered the phone and used colourful language to explain that she would not receive any money.

Dain Daung’s lawyer then issued a notice in state-run newspapers on May 28 that he was not responsible for his daughter’s actions, and that he would take legal action against anyone who mentions his name in connection with his daughter’s case, either in print media or on social media.

Frontier attempted to contact Myat Noe Oo and her father several times but their phones went unanswered.

After May Thu was unable to get her money back, she submitted a complaint to police North Okkalapa Township. They refused to open a case and told her instead to file it at the court.

Her lawyer, U Nay Sithu Zaw, told Frontier on July 16 that police had finally opened the case on July 7 after being ordered to do so by the township court.

May Thu, who runs a wholesale and retail seafood business, said she still has little hope of seeing the money or prosecuting Myat Noe Oo.

Despite her experience, she continues to participate in savings programmes – but only through people she knows personally, and never online.

“I can’t save money myself,” she said. “So the system is good for people like me.”