Myanmar factory labourers are being pushed to breaking point by rising commodity prices and the junta’s failure to raise a minimum wage that has stayed flat for five years.

By FRONTIER

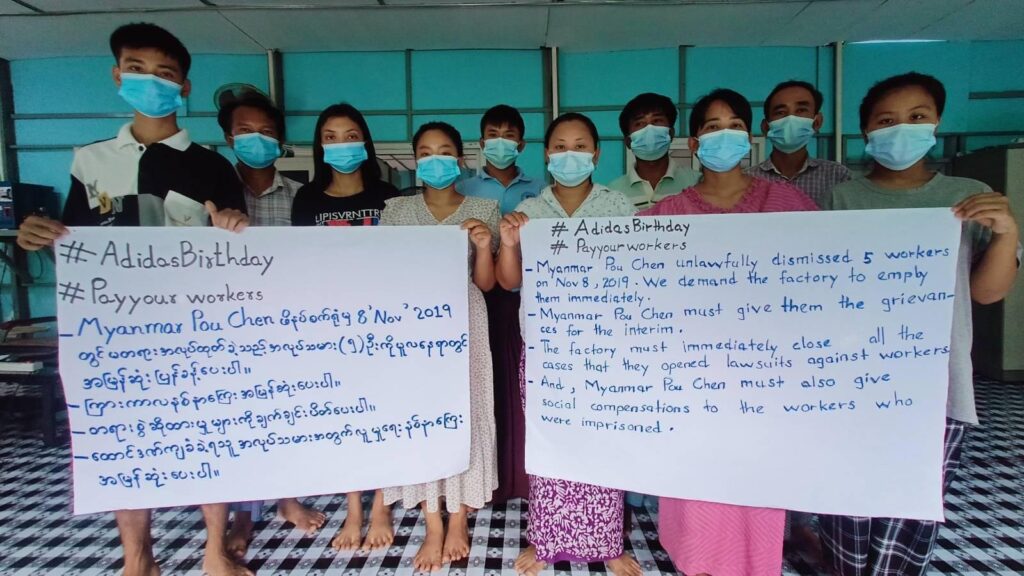

As garment workers gathered at Yangon’s teashops and beer halls to watch the recent World Cup, they may have recognised some of the footwear on display. While the tournament took place in distant Qatar, employees of a factory producing boots and trainers for Adidas, the German brand equipping many of the teams, were protesting low wages and the summary dismissal of 26 of their colleagues.

Myanmar Pou Chen Co Ltd, a Taiwanese firm that is considered the world’s largest branded OEM sports shoe manufacturer, had sacked the workers from its factory in Yangon’s heavily industrialised Shwepyithar Township in October. The company justified their dismissal by accusing the group of taking an unexplained leave of absence. Before being let go, they had led a three-day strike to demand that their minimum daily wage be increased from K4,800 to K8,000 (US$2.60).

The 26 workers took their case to the junta’s labour department but received no redress. Although Adidas itself requested in early November that they be reinstated, Myanmar Pou Chen refused, instead transferring them 10 days wages and their October salary as severance pay. In response, the group says it will return the payments and continue to fight until their demands are met.

The workers say they led the October strike because their salaries can no longer keep pace with living costs, which have risen rapidly since the February 2021 coup without a corresponding increase in the national minimum wage.

They knew they faced steep odds in pursuing their rights. In a few rare cases since the military takeover, striking workers have had their demands met. However, such victories say more about the conciliatory attitude of a particular factory’s management than the junta’s ability or willingness to enforce basic labour rights.

One of the strike organisers, Ma Phyo Thida Win, worked in the quality control department at the factory for more than four years before she was sacked. The 26-year-old had earned Myanmar’s minimum wage of K4,800 ($1.55 at the current market exchange rate) for an eight-hour day. She said that, on some days, she worked two hours’ unpaid overtime when there were many orders to fill.

Phyo Thida Win says she was able to make ends meet before the coup, when prices for commodities such as rice, cooking oil and salt were stable. A combination of a low daily wage and higher commodity prices since then have made life a struggle.

“The salary I received became barely enough to feed me, and we had to pay more for our dormitory accommodation. Then we were forced to increase our workload and were threatened with dismissal by supervisors if we could not handle the extra work. They would tell us that there were people lining up outside the factory who would be happy to take our jobs,” she recalled.

On the morning of October 25, the strike began when about 1,700 of the 7,000 employees at Myanmar Pou Chen rallied outside the factory to demand a pay rise. The striking workers knew it was risky for such a big crowd to gather at a time when the military was brutally cracking down on all types of protest. Moreover, an angry protest by the factory’s employees in March last year, shortly after the coup, had led to the firm temporarily suspending its Myanmar operations rather than fulfilling their demands.

Phyo Thida Win said soldiers had appeared within about 10 minutes of the protest. A few minutes later, she and six other workers were brought before factory managers and two army officers at the company office.

“We knew we could get fired. The company had warned us about its ‘No work, no pay’ policy, but we ignored the warning because we had the right to express our demands,” she said.

Unbearable living costs

The 2011 Labour Organisation Law legalised trade unions after decades of repression. Although the law is still on the books and workplace unions remain legal, the coup has rolled back the limited powers workers had won over the last decade. One month after the military seized power last year, it outlawed 16 unions, further decreasing representation for Myanmar’s workers. Even at the height of unionisation, just one percent of the workforce had backing in the case of a workplace dispute.

Meanwhile, figures from the International Labour Organisation show the value of Myanmar’s garment sector grew five-fold between 2011-19. The sector contributed 29pc of the country’s total export value before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

In 2013, parliament passed Myanmar’s first ever minimum wage law. The legislation stipulated that a committee consisting of employers, labour unions and labour ministry representatives would convene to review the minimum wage every two years.

In 2015, it was set at K3,600 per working day (around $2.25 at the time), while in May 2018, reflecting a period of rapid economic growth, the figure was raised to K4,800 (around $3). It has stayed at this level for the five years since.

However, competition to earn even this meagre wage increased when, in 2020, COVID-19 lockdowns and global supply and demand-side shocks caused factories to shutter and workers to be laid off in their thousands. While the industry looked forward to a rebound last year, the economic fallout of the coup – with the World Bank measuring an 18pc contraction in GDP – meant many workers didn’t get their jobs back.

At the same time, the drastic decline in the value of the kyat, combined with inflationary pressure on basic goods, has meant that even those in full-time employment have experienced a huge fall in living standards and have struggled to support their families.

By and large, factory bosses have not compensated employees for the decline in real earnings, and some have instead taken advantage of the collapse of regulatory frameworks to put an even greater squeeze on garment workers.

‘The company is not taking responsibility’

Ma Khaing Thazin Phyo, 20, a clerk at Myanmar Pou Chen, was among the workers who were sacked for helping to organise the strike.

She had worked at the factory for just over a year and for a monthly salary of K144,000 ($46.50), she made inventories of raw materials. Despite the low pay, conditions were less harsh than for workers on the production lines.

Khaing Thazin Phyo learned she had lost her job when she returned to work after the three-day strike. She said that, suddenly deprived of a regular income, “I’m really struggling. I’ve borrowed money from friends to survive for now. The company is not taking responsibility for what it’s done,” she told Frontier.

The United Kingdom office of the independent, donor-funded Business and Human Rights Resource Centre was alerted to the sackings and emailed Adidas on October 31.

In a response on November 3, the company said it had “objected strongly to these dismissals, which are in breach of our Workplace Standards and our long-standing commitment to upholding workers’ freedom of association. We are investigating the lawfulness of the supplier’s actions and we have called on Pou Chen to immediately reinstate the dismissed workers.”

Myanmar Pou Chen did not respond by press time to Frontier’s request for comment. Phyo Thida Win told Frontier that rather than resolving the dispute, Pou Chen had forced the workers to take their final salary, which did not include compensation for length of service, and to leave the premises.

Assertive junta, empowered bosses

Figures from the junta’s labour department show that there were more than 410,000 workers in the garment sector at the end of October, and that the industry employs more than 2,600 foreigners, many of whom fill managerial positions.

The ordinary workers face chronic insecurity as the military regime turns a blind eye to labour law violations. At the end of November, it was reported that all 300 employees at another factory, the Yangon Fukuyama Apparel Co Ltd factory in Shwepyithar Township’s Wartayer Industrial Zone, were dismissed on the evening of November 29, allegedly without justification.

When the workers gathered at the factory the next morning to ask why they were dismissed, they were not allowed to enter the compound. The junta-appointed district administrator is alleged to have gone to the gates of the factory to turn them away.

A 24-year-old woman who worked in the cutting department at Yangon Fukuyama Apparel for more than four months claimed that, despite signing employment contracts, factory bosses had kept all versions and had not returned them to employees, making it difficult for them to make legal claims.

She claimed that she had earlier been threatened with dismissal for taking unannounced leave, which she was later not remunerated for despite the provisions of her contract, and that overtime pay was withheld if she failed to meet production targets.

“The employment contract stipulates that employees can be dismissed after taking four leave days without notice. I was dismissed after taking leave on just two days without notice. There was no workers’ representative who could stand by our side and help us to negotiate,” she said.

“I want to demand immediate action against the factory for violating our labour rights,” she said.

Daw Myo Myo Aye, director of Solidarity Trade Union of Myanmar, told Frontier on that strikes were increasingly occurring at garment factories because of unjust behaviour by management against workers demanding their rights.

When workers are sacked, the terminations should be in line with labour laws, which require one month’s notice and any advance pay to which they may be entitled, Myo Myo Aye said.

“Now, they’re being fired by employers for no reason. They were doing their jobs and got sacked without any advance notice and didn’t receive the compensation they’re entitled to,” she said.

Myo Myo Aye said some employers had even vanished after protests by workers.

“There were three incidents in Yangon after the coup in which workers had gathered outside a factory to protest and had been ordered to go home, and when they returned the next day, the employer was gone, equipment had been removed from the factory and the workers were jobless,” she said.

“More than ever, workers are losing their rights because they’re asking for a rise in their salary.”

Wages of fear

Workers and labour union members were among the first to protest against the coup and many of them have paid a price in junta suppression. The Solidarity Trade Union of Myanmar was one of the 16 trade union and civil society groups that the junta designated “illegal labour organisations” on February 28 last year. This prompted the organisation to shutter its offices in Yangon and Mandalay, although its members continue to operate underground or in exile.

Myo Myo Aye was imprisoned in April this year before being released in October, and spent 45 days in solitary confinement. She said that despite this persecution, “We continue to help the workers as much as we can because that’s what we do.” She added that since the coup, “We have been accused of inciting riots because we were helping workers. We were blamed for some factories closing.”

Myo Myo Aye said the situation for upholding workers’ rights was “impossible” because the state labour bureaucracy was corrupted and the committee for negotiating the minimum wage was compromised, with only pliant labour representatives allowed to take part.

“The only representatives that are given the right to discuss the minimum wage in the committee are people representing merchant seamen and agricultural workers – so they cannot really debate the minimum wage for those in other fields, like garment workers,” she said.

On November 25, the junta’s labour department announced it would convene the committee. However, early this month, its permanent secretary U Nyunt Win told VOA Burmese that no increase was planned because of the poor state of the economy.

Referring to junta leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing by his self-awarded title, Nyunt Win said: “The Prime Minister himself said to raise the salaries of government employees only after the country’s economy has improved, as well raise the basic salaries of workers in the private sector.”

He added that garment sector salaries couldn’t be raised because factories were incurring higher raw material costs due to exchange rate fluctuations while also receiving fewer orders.

Myo Myo Aye considered this a mark of how low the sector had fallen. At meetings with workers in industrial zones before the coup, she said there had been hopes that the minimum daily wage would rise to K10,000.

“Now all their dreams are gone,” she said.