A long-running dispute between the government and a mining company over a debt has shuttered dozens of gold mines in the Yamethin area of Mandalay Region, crippled small operators and left thousands out of work.

By KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE

YAMETHIN IS a nondescript town in southern Mandalay Region, about halfway between Nay Pyi Taw and Meiktila on the Yangon-Mandalay Highway. It rarely makes news headlines. But in recent months it has become the scene of a bitter dispute between the government and a mining company that was granted a licence in 2011 to mine for gold on 6,105 acres (2,470 hectares) of land in the Moehti Moemi area near Yamethin.

The dispute relates to the failure of the company, National Prosperity Company Ltd, to pay the amount of gold specified under the contract to the No. 2 Mining Enterprise, under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. In February, the ministry ordered NPC to halt operations.

Caught in the middle of the dispute are the hundreds of employees of smaller companies – 34 in total – who were working with NPC, either as partners or sub-contractors. As a result of the February order, they have not been able to work for several months. But they don’t blame the government; most are angry at NPC for not paying the required amount of gold to the government.

The entrance to the mine town at Moehti Moemi. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“We have been mining here since the time of the military junta,” said U Tin Tun, manager of Gandaya Sein, which operated four adits, or mine shafts, at the site before work was halted.

Canadian firm Ivanhoe discovered gold in the Moehti Moemi area in 2000. After extensive drilling, it submitted a joint venture proposal to the military government in 2004 but the project never moved forward, and Ivanhoe eventually exited the country after selling its copper mine at Monywa in Sagaing Region.

Tin Tun told Frontier that after gold was discovered the military government banned mining at the site by putting in place an emergency order under section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Workers though would regularly bribe local government officials to gain access to the site and dig for gold.

“They also levied tax on us, depending on the production amount,” Tin Tun said during a recent protest at the site, held by protesters calling on the government to allow operations to re-start. “Though they said it went into the state’s fund, we all know that it didn’t.”

An ongoing dispute

The illegal mining came to an end in 2011 when the quasi-civilian government led by the Union Solidarity and Development Party conducted a tender to permit mining in the area. NPC, headed by U Soe Tun Shein, won the tender and the original contract was signed in September 2011.

Under the agreement, NPC would have to pay 5.577 tonnes of gold to the government over five years. But the company says it soon realised gold reserves were not as high as first believed, and at NPC’s request the government amended the contract. While the amount of gold NPC owed did not change, the production period was extended to eight years, after which NPC could mine for another 17 years and retain 70 percent of the gold.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

NPC was again unable to keep up with the repayments. After ordering mining to end in February, the government terminated the contract on May 17.

“As Amyothat Kyeepwar Yay won the tender, they invited small mining firms to join them,” Tin Tun, using the Myanmar language name for NPC, told Frontier from a small office near one of his adits.

He said he believed that NPC didn’t have the required capital when it started the gold mining, and instead used investments put forward by the partner companies.

But the company has disputed this. Soe Tun Shein said the company invested US$2 million in the mine as required under the contract in addition to the money raised from partners.

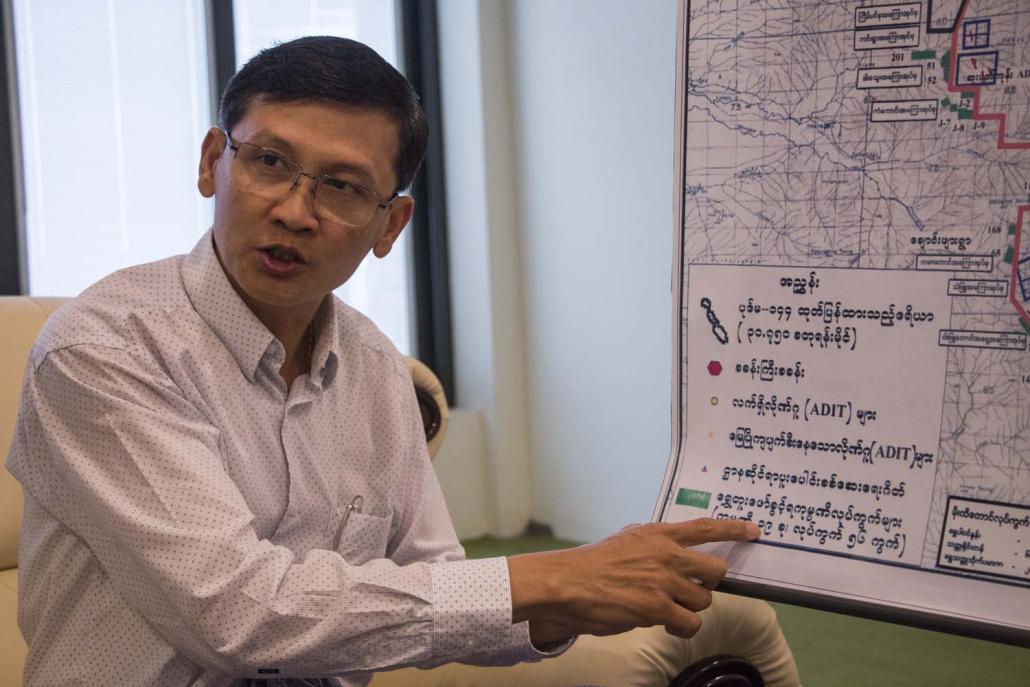

“We provided the bank information showing that the company had this amount of money,” he told Frontier at his office in Yangon’s Hmawbi Township on June 20.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

Soe Tun Shein said that a map used by the ministry when it was deciding on the tender showed that 39 mining firms were operating at 56 sites near the block A area of the mine, despite mining being illegal in the area.

“These firms mined in block A at nighttime,” said Soe Tun Shein. “Security officials such as police and soldiers took tens of millions of kyat each month in bribes.”

When NPC was awarded the tender, it negotiated with these companies to try and stop illegal mining in the area, he said.

The miners came on board in two categories, he said, either as “partners” (mate phat), who bought shares in NPC, or as “sub-contractors” (paung see).

Soe Tun Shein said that 28 of the 39 companies joined as partners, and those that did were required to provide less gold tax to NPC, which would then pass on a set amount to the government. Partners were able to buy NPC shares for K100 million; each share allowed them to mine at three adits.

National Prosperity Company chairman U Soe Tun Shein points to a map of the mining concession. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Tin Tun said he paid K500 million for five shares in NPC and was allowed to mine at 15 adits in the area. His company paid up to 50 percent of the gold it produced to NPC for almost a year, after which it was reduced to 40 percent and then 30 percent. Altogether Gandaya Sein has given NPC 135 kilograms of gold, he said.

Tin Tun estimated that NPC had received at least 989kg of gold from its partner companies and subcontractors over the five years of production.

“If NPC had handed [this amount] of gold to the government, they could have probably avoided this situation,” he said. “Now we are also stuck in a dilemma, even though we paid what we were expected to pay.”

Soe Tun Shein said that what the company had received from the smaller companies needed to be used to pay for products and services, including transportation and taxation.

He said that NPC received barely 160kg of “net gold” from more than 40 partners and sub-contractors.

He added that only about a dozen of the companies had complained about the situation.

“What they said is not true. We are ready to be investigated or audited, and if what they say is true, give me a life sentence,” he said.

Originally from Taunggyi in Shan State, Sai Ye Naing has spent most of his 30 years in the mining industry searching for jade at Hpakant. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Some of the companies have accused NPC of mining in an area where Canadian giant Ivanhoe discovered large deposits of gold, before it left the country in 2011, but only allowing its partners to explore in areas with less gold deposits.

Again, NPC disputes this.

“For mining, we have two parts,” said Soe Tun Shein. “One is the production area where we know gold deposits are located, and another is studying which area has the highest content of gold. So we first mined in the areas where Ivanhoe did studies.”

A failing venture

Sai Ye Naing is originally from Taunggyi in Shan State. For most of his 30 years in the mining industry he was based in the jade-rich area of Hpakant in Kachin State. But in December 2013, he moved to Moehti Moemi in search of gold.

“A friend told me that business is good, and suggested I came here with K1 million in capital, 10 workers and a generator,” Ye Naing said.

He said the investment only allowed him to explore at one adit that had been depleted by the gold miners who operated in the area before NPC was awarded the contract.

“The adit is an old one, and the gold content is low,” he said. “So I had to mine for three months to get the amount of gold others could get in a month.”

He extracted around 13kg of gold; about half he paid as a tax to NPC, he said.

He has not been able to work at the mine since December 2017, when his adit collapsed. He has asked NPC for permission to mine at a new adit, but has not yet been granted approval.

“This is my first gold mining experience. It’s really bad,” he told Frontier as he stood at the entrance to the mine, the gates of which were locked.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

He estimates that he spent more than K200 million since moving to the area four-and-a-half years ago.

“As the mine work was suspended, we are in big trouble. It would be great if we can resume our work soon,” he said.

A dispute with the ministry

NPC is one of several companies that the government plans to sue for failing to pay the amount of gold specified in their contracts, said U Than Daing, managing director of No 2 Mining Enterprise.

Everyone agrees that NPC has not paid the required 5.577 tonnes of gold. Last month, Than Daing told Frontier that NPC still owed the government 1.78 tonnes.

But Soe Tun Shein said the government misled his company about the area’s gold reserves. In particular, he said, NPC had been given information based on “outdated” Ivanhoe data that did not take into account the rampant illegal mining that had occurred.

He said that the map provided to the company during the tender process showed a “huge” supply of gold, at about 2.623 tonnes over 2,000 acres, a gold reserve of 38.06 grams per tonne.

“But we mined only about 60 viss [100kg] of gold per month, because the reserve was found to be only 9.01 grams per tonne,” he said. One viss equals about 1.63kg.

Soe Tun Shein also accused No 2 Mining Enterprise of violating agreements made during a meeting, held on July 13, 2017, between company directors and government officials, including Minister for Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation U Ohn Win.

He said both sides agreed the debt stood at 246kg and the company said it would pay back the outstanding amount over a period of 11 months, ending in June 2018. But in November, the ministry stopped accepting the payments, he said. “[The managing director] ordered us to suspend all production while we were following instructions made by the union minister,” he said.

A vendor waits for customers in the market at Mine Myo. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

The order to halt payments had come after Ohn Win told parliament in October that the government was soon to collect gold owed to it by private companies.

“That was just four months after we started doing what he had told us to do in order to solve the issue,” said Soe Tun Shein.

He said the company continued mining because it considered the instruction from the minister to supersede that from the managing director, who holds a lower position.

“And anyone with knowledge about the mining industry knows that any large-scale mine can’t stop production immediately,” he said. “If the [No 2 Mining] Enterprise sues us in order to collect that amount of gold, we will also fight for our loss.”

Suffering on the ground

The partners, sub-contractors and workers are largely collateral damage in the dispute between the government and NPC. And they are suffering. In mid-June hundreds of miners and company staff staged a week-long protest on the streets of a large village they call Mine Myo (Mine Town) in the Moehti Moemi area.

The population of the area has fallen from 15,000 to about 5,000 in a few years due to a lack of job opportunities, said U Win Chit, who was appointed administrator of Mine Myo by the General Administration Department in Yamethin based on NPC’s recommendation.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

“I have been selling things here for a decade,” said Win Chit. “The town drew more and more people after Amyothar Kyeepwar Yay started producing gold in 2012.

“But after the government ordered [the company] to suspend production, workers lost their jobs. Then they started leaving the town,” he said. “Businesses are in the worst situation right now.”

During the demonstrations, held between June 10 and 16, protesters called on the government to reconsider the decision to revoke NPC’s mining contract.

In 2015, Ma Thin Hla moved with her husband, U Khin Aung, to Mine Myo from Ann in Rakhine State. Khin Aung got a job with NPC and was earning K200,000 a month.

“My elder daughter just passed the matriculation exam, but as his father lost the job, I have no idea what to do for her education,” she told Frontier.

“Now we are relying on the rations provided by the company,” she said, adding her family received a large bag of rice, a viss of oil and some dried fish each month.

The protesters said they will march to Nay Pyi Taw and Yangon unless the government responds their demand in a week.

“We don’t know what the problem was between the government and the company,” Thin Hla said. “What we know is we are in big trouble as the company stopped mining.”