The vast sums donated to pagodas are managed by boards of trustees but investigations at two of the nation’s most revered pilgrimage destinations have uncovered discrepancies involving millions of kyat.

By MRATT KYAW THU & KYAW PHONE KYAW | FRONTIER

Photos THEINT MON SOE aka J

THERE’S A Myanmar proverb that helps to understand why the country’s majority Buddhist population gives so generously to pagodas and monasteries.

“Even if you give away something as small as a banyan seed, if you do so with genuine good intention the reward for your generosity may be as big as a banyan tree,” says the proverb, one of many in Myanmar that extols the virtues and spiritual benefit of giving generously.

Well-appointed monasteries and pagodas can be seen even in small villages throughout the country due to the generous giving of the country’s Buddhists.

It’s also the reason why Myanmar topped a global index of generosity for the third consecutive year in 2016. The United States and Australia were second and third, respectively, on the World Giving Index, an assessment of generosity in 140 countries and territories compiled by the London-based Charities Aid Foundation.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Almost all donations made by Myanmar Buddhists are to build or maintain monasteries and pagodas, or to support monks and nuns.

soelwin.jpg

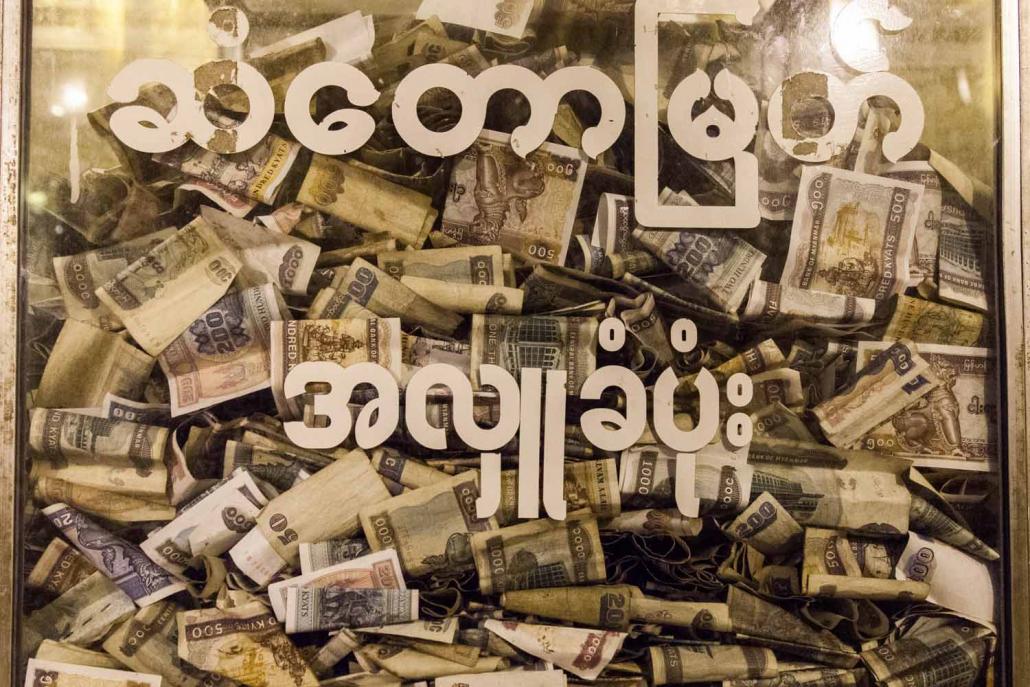

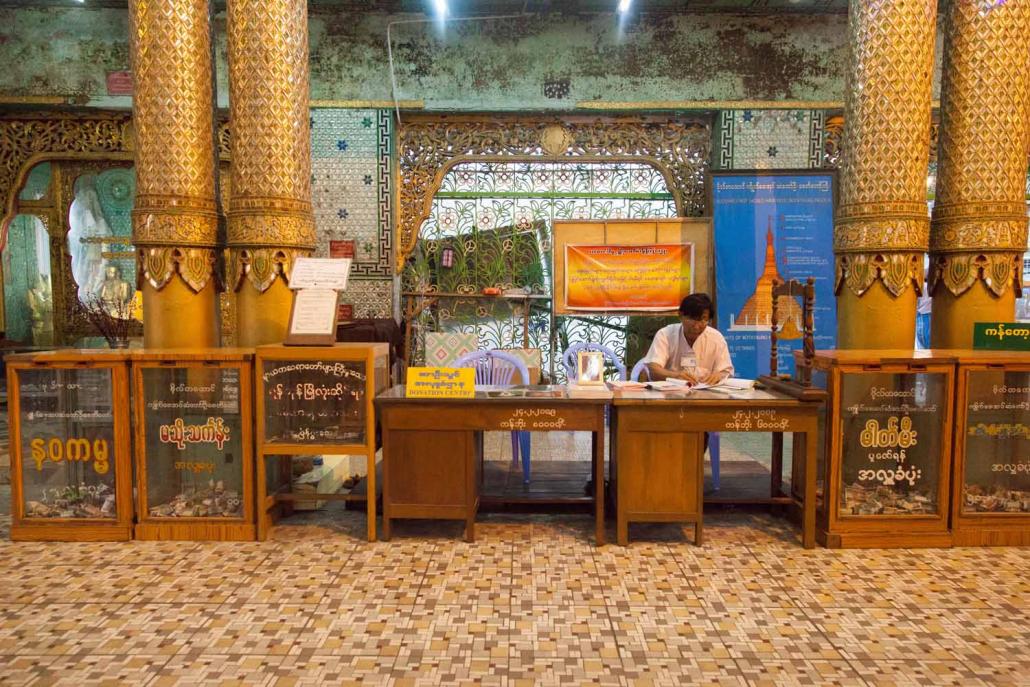

Of the country’s famous religious sites, the most venerated is Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda, to which many Buddhists have donated money or jewellery. There are donation boxes everywhere on the terrace of Shwedagon where devotees can give to the sacred landmark, and in doing so earn spiritual merit as a reward for their generosity.

The Shwedagon is fabulously wealthy because of the donations it receives. The figures for 2016 are not yet available but the pagoda’s income from donations in 2015 was K18.6 billion, down slightly on the previous year’s K19.9 billion, which was nearly double the K10.1 billion it received in 2013. As well as donations, the pagoda also generates income from the six departments managed by its trustees.

Their total estimated income for 2016 is about K57.6 million, which includes K35 million from remnants of gold taken from the pagoda, which are washed with sand and then resold, K5 million from selling the guano of the huge bat population that lives at the pagoda, and K4 million from the sale of wax from melted votive candles.

jtms-donations-16.jpg

Funds from donations are used for restoration, redecoration, renovation and maintenance, and income from the various departments covers administrative and management costs, including salaries, the board of trustees said in a January report.

Spending on restoration and related activities was K8 billion in 2015, K6.2 billion in 2014 and K7.2 billion in 2013, but Frontier was unable to acquire figures on management and administrative costs.

The Shwedagon has a total workforce of 1,392, of whom 970 are permanent employees who earn between K120,000 and K380,000 a month, depending on their roles. The rest are casual day labourers.

“Our pay scales are based on those of public servants and the highest ranking person receives the same as a deputy director general,” said U Tun Aung Ngwe, a retired major who is chief of staff at the Shwedagon.

The 10 members of the board of trustees each receive K385,000 a month for “medical expenses”.

Figures provided by the trustees show that the Shwedagon’s total donation income from 2013 to 2015 was K48.73 billion and expenses for the period were K21.47 billion, leaving a balance of K21.46 billion for the three years. The total balance at the Shwedagon is K59 billion.

“We don’t make donations from our funds to other pagodas because donors who give to the Shwedagon Pagoda want it to use the money, according to custom,” Tun Aung Ngwe told Frontier.

jtms-donations-05.jpg

The trustees supervise the collection of money from donation counters and boxes and it is counted by a team of 30 people each day at 10pm. The money is kept in a safe overnight and deposited the next morning in a state-owned bank.

“We do not need to pay any tax on donations or on departmental income,” said Tun Aung Ngwe, adding that the Office of the Auditor General in Yangon Region examines the pagoda’s books every year.

Another famous religious site in Yangon is the Okkalapa Myo Oo Zedi, or pagoda. Its financial situation differs significantly from that of the Shwedagon.

The Okkalapa Myo Oo Zedi, in South Okkalapa Township, was built in 1990 and its board of trustees says it has savings of K280 million.

The pagoda’s income from donations is about K2 million during months that mark special events on the Buddhist calendar and lesser amounts at other times of the year.

The monthly income from its departments is K1.1 million, which covers the salaries of 18 permanent staff. Income from donations is used only for renovations, redecoration and maintenance.

The pagoda’s biggest expense is the cost of regilding the zedi, which has happened three times since it was built 27 years ago. There are plans for the pagoda to be regilded for a fourth time this year, at an estimated cost of K200 million.

jtms-donations-13.jpg

“I was one of the people who decided that we needed to build a pagoda in the centre of the township; now all are going fine,” said U Ko Yi, 77, who heads the board of trustees and has been its secretary for 15 years.

“I have never drawn a salary since I became secretary,” said Ko Yi, who worked at the Ministry of Commerce under the U Ne Win regime and has long been involved in religious activities in South Okkalapa.

There is yet to be an election to choose the pagoda’s trustees. “There is no system yet to hold an election for the trustees,” Ko Yi said.

It’s a similar story at the Shwedagon Pagoda.

A member of its board of trustees, U Thaung Htike, 64, told Frontier he could not remember the last time there was an election of board members.

Neither Ko Yi nor Thaung Htike could say when an election for trustees would be held at their respective pagodas.

Thaung Htike, a retired colonel and the Deputy Minister for Sports in the U Thein Sein government, said the rules and regulations for trustee elections at the Shwedagon were being amended.

U Thaung Htike was appointed to the board of trustees late last year, a decision he said was “the result of previous karma”.

“A long time ago, our very senior trustees were elected, but how can be hold an election now? If we have an election the people around the pagoda will have to vote. The Shwedagon is a state pagoda and that is why we are appointed according to the rules and regulations,” he said.

jtms-donations-03.jpg

Thaung Htike declined to say who was responsible for his appointment as a trustee. The rules say trustees should be aged under 70 and their appointments are for five years. Some former trustees served for 10 years.

He pledged that if any discrepancy was found in the pagoda’s accounts he would resign immediately as a trustee.

“Concerning money, if something’s wrong because it was not done properly or was unethical and if I [was accused], I would resign immediately. I guarantee that,”

Thaung Htike said.

Most decisions about the pagoda’s management are made by the trustees. Matters of special importance are decided at a meeting of senior monks and trustees and must be approved by the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture.

At another of the nation’s most revered Buddhist sites, the Kyaikhtiyo “Golden Rock” Pagoda on Mon State, there has never been an election for the trustees, and the previous board issued contracts to businesspeople to manage its donation box collections.

After a new board was appointed last October it reformed the donation collection system and made a disturbing discovery.

Donations collected under the new board over the 25 days from October 16 to November 9 totalled K42.2 million – more than the K40.8 million received during the entire previous year, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture said in an announcement.

A similar discovery was made at another revered site, the Shwe Settaw Pagoda in Magway Region.

After the National League for Democracy-dominated Magway regional government came to power it undertook a sweeping reform of the pagoda’s administration and financial management and arranged an election for its board of trustees.

The reforms were proposed by the regional Minister for Labour, Immigration and Population, U Nay Myo Kyaw, who had been assigned to investigate the pagoda’s management by Magway Chief Minister U Aung Moe Nyo.

Apart from the need for new rules and regulations for trustees, the investigation found that funds had been misused.

An election for a new board was held on November 30 under the revised rules and regulations. They provide for elections every three years for trustees, and can only run again if they are nominated.

“No more corruption, no more favoured men,” said Nay Myo Kyaw.

A popular pilgrimage destination, Nay Myo Kyaw estimated that the pagoda’s total income should have been about K2 billion a year for the 30 years it was managed by previous boards of trustees. He said the Shwe Settaw Pagoda has a bank deposit of K3.7 billion and owns two viss of gold, or about 3.26 kilograms of the precious metal.

“I don’t want to talk much about the past because the pagoda’s yearly festival is coming soon and people will be aware that there have been changes,” Nay Myo Kyaw said, referring to a three-month celebration beginning in mid-February. “For example, maintenance work that cost K20 million was costing K60 million under the previous trustees,” he said.

“The systems, administration and financial management were corrupt for over 30 years,” the minister said. “Under previous regimes, trustee boards were in the pocket of the authorities and were more interested in profiting for themselves than in raising money for the pagoda.”