But critics say putting pressure on children to excel is hampering their all-round development.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

WHEN DAW Khin San San was teaching at a high school at Tanai in Kachin State, most of her students were the children of members or supporters of the Kachin Independence Army, and most of the teachers were the wives of Tatmadaw officers.

Khin San San’s husband was a Tatmadaw captain.

It was 1991, three years before the KIA and the Tatmadaw were to sign a ceasefire that held until June 2011, a few months after the Union Solidarity and Development Party government took office.

Khin San San, now 59 and retired, and the other teachers at the Tanai school would provide tuition free of charge in their homes to children whose fathers were regarded by the Tatmadaw as the enemy.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

In 1993, Khin San San’s husband was killed in a helicopter crash, when his Tatmadaw chopper went down between Tanai and Myitkyina, and she moved to Yangon. She continued teaching but the pay was not enough to raise her children and after a few years she went into business.

“I never wanted to make extra money from providing after-class tuition because I regarded it as unethical,” she told Frontier. “Most of my former teaching colleagues have become rich and comfortable from the extra tuition classes they continue to provide.”

The decline in education standards in the decades after General Ne Win seized power in 1962 contributed to the steady growth of the tuition industry in a nation where academic qualifications are prized and teachers are exalted.

Private tuition is available throughout the country except in the most remote areas or those affected by conflict.

In Burmese, tuition is known as kyu shin and it has a negative connotation; parents often view it as a necessary evil. The meaning of the word has diverged from the original English term, which has a simple definition: to teach, especially to a small group or individual.

In Myanmar, kyu shin typically refers to a specific kind of teaching: paid, after-class instruction, often by the students’ classroom teacher. It is associated with corruption and seen as symptomatic of the failings of the education system.

The pressure on students to excel has resulted in private tuition being regarded as essential, much to the dismay of public education specialists who see it as a cancer on the school system. It is also illegal for government teachers to provide after-class tuition.

However, the tuition industry has become so pervasive that the law prohibiting teachers at government schools from providing extra-curricular instruction has been flouted openly for more than 30 years. The Private Tuition Class Law was enacted in 1984.

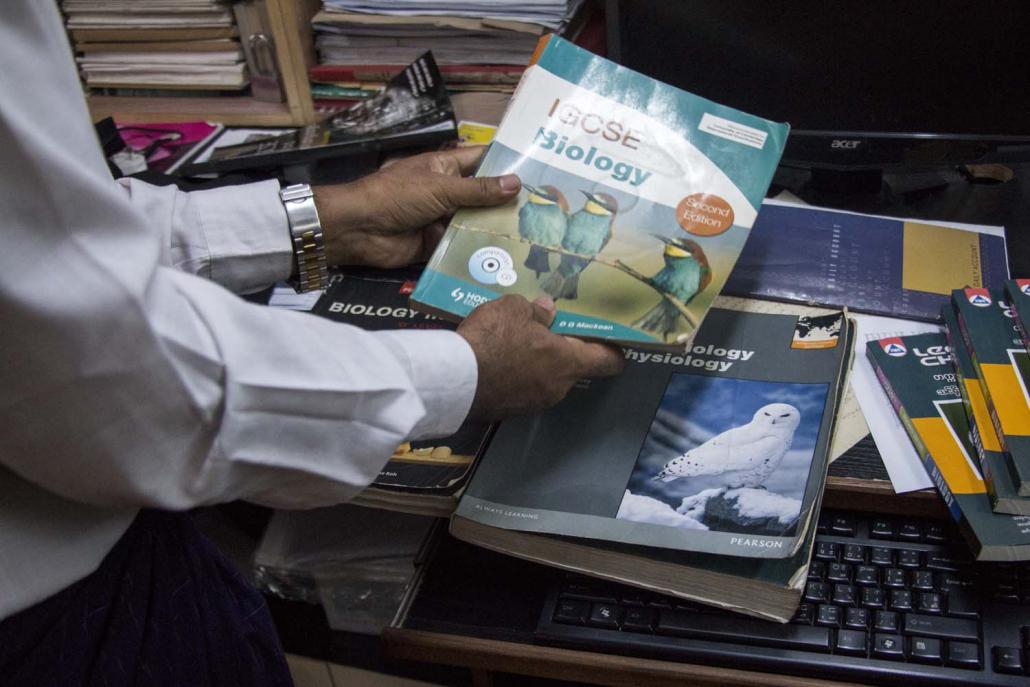

A private tutor for three decades, U Soe Win Oo – who is better known as Dr Bio – has seen first-hand the effect of the tuition culture on the country’s education system and its young people.

U Soe Win Oo, a tutor with three decades of experience who is better known as “Dr Bio” says the emphasis on tuition is harming children’s all-round development. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

He’s a long-time advocate of education reform and a political activist; during the national uprising in 1988 he was one of the leaders of the Medical Students’ Union, and later led the NLD-Youth branch in Ayeyarwady Region.

“[Tuition culture] had a big impact on all children, starting from when we were children,” said U Soe Win Oo, “Since students have to spend at least an extra three hours studying, they lose their time to develop themselves in other ways. Their loss is a failure of the country.”

A burden on families

On the evening of June 2, U Khin Zaw Win, 54, was celebrating with former colleagues at the motorcycle taxi stand in Yangon’s outer South Dagon Township where he once worked.

The proud and delighted father of two was buying drinks for his friends because he’d learned earlier that day that his younger daughter, Ma Hnin Wut Yee, 16, had passed the crucial matriculation exam with four distinctions.

Khin Zaw Win and his wife had shouldered a heavy financial burden to ensure their daughter’s success in the exams, which guaranteed admission to the university course of her choice.

Khin Zaw Win reckoned that private tuition fees had devoured 80 percent of the cost of educating his daughter for her last two years at high school.

“Every month for the past two years, we were paying K50,000 for tuition fees and K60,000 for study guides,” he told Frontier.

Khin Zaw Win earned about K300,000 a month as a motorcycle taxi driver. It wasn’t enough to cover the cost of educating his daughter and he and his wife had to find a way to increase their income. They planned ahead and took a risk, establishing a successful laundry service in 2015 with three washing machines.

Hnin Wut Yee believes she might have passed the matriculation exam without tuition, but acknowledges that such an achievement would have been difficult.

“Without tuition it would have been very hard for me just to pass and there’s no way I could have received even one distinction,” she said. “With four distinctions, I hope I can pursue my dream of becoming an architect.”

There is enormous pressure on students to excel in their matriculation exams and be admitted to the university course of their choice. This is one reason why private tuition has come to be regarded as indispensible.

Is it needed?

Education specialists say private tuition is beneficial, but stress that it should not be provided by a student’s teacher or hamper a child’s all-round development.

Ms Erina Iwasaki, a Japanese educator who spent much of her childhood in Myanmar and studied in France and the United States, is curriculum director at Yangon’s Khayay private school, founded by her parents in 2004.

Iwasaki is a firm believer in quality education in which students have equal access to teaching.

“It is important that all students get their learning in the classroom. After school, time must normally be allocated to other activities that interest the student and support other parts of the student’s development,” she told Frontier.

Students outside Basic Education High School 1 in Yangon’s Dagon Township. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Soe Win Oo strongly agrees. He also says there are many reasons why students at government schools are not taught effectively and need extra-curricular tuition.

“There is still a big gap in the teacher-student ratio, state schools lack necessary facilities, such as laboratories, proper playgrounds, and counselling services, and the teaching and assessment methods are still based on memorisation,” he said.

A common criticism of memorisation is that it fails to nurture critical thinking because it teaches children to answer questions but not to ask them. Rote learning also places huge time demands on students, who are required to ingest and memorise a large amount of information.

Although education specialists with international training are against children being put under pressure to compete and be the best, most government teachers and parent groups believe that encouraging competition is important.

This competitiveness has been evident with the recent introduction of mandatory, nation-wide kindergarten classes. One of the biggest challenges that kindergarten teachers face is over-eager parents, who wonder why their children aren’t being taught things like the alphabet or mathematics.

A critic of taking the fun out of kindergarten and replacing it with pressure to learn is Dr Aung Aung Min, deputy director general at the Department of Higher Education.

“Teachers at kindergartens should only read stories to children and let them play around and do things among themselves, but parents don’t understand this and send the kids to tuition and make them learn the Grade 1 subjects a year in advance,” Aung Aung Min told Frontier.

Another weakness of government schools was a shortage of teachers with appropriate qualifications.

“We still need to train teachers to meet the needs of each school,” Aung Aung Min said, citing the example of a teacher who graduated with an English major but was sent to a school where she was required to teach Burmese.

He also said teaching and assessment methods needed to focus on encouraging critical thinking rather than being based on rote learning and the ministry was trying to introduce step-by-step changes.

Big business here to stay

On several occasions, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has criticised Myanmar’s tuition culture. During a trip to Thailand in June 2016, she told Myanmar migrant workers in Mahachai that it was an issue that needs to be addressed, while in a letter to the Nobel-Myanmar Literary Festival, held in January 2016, she complained that students had little time to read books outside the school curriculum because they were under pressure to memorise the prescribed texts.

However, most education specialists predict that demand for extra-curricular tuition will remain strong in the foreseeable future. Some are at least doing their best to make it more professional and ethical.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

The tuition industry has provided opportunities for young, tech-savvy entrepreneurs, who are seeking to improve the tuition industry and address some of the problems parents and students face.

They include the founders of a start-up called MMTutors, which was launched last year and helps to match students with the most appropriate tutor.

Finding a tutor who matches the learning ability of their child can be challenging, said MMTutors chief executive Ma Phoo Pwint Eain.

“Our main objective is to ensure our students learn efficiently,” she told Frontier.

MMTutors provides regular performance indicators and its online service offers the convenience of instant communication between tutors and students. Phoo Pwint Eain said this could save families money on transportation and meant children spent less time in traffic jams travelling to classes.

Iwasaki said doing away with after-class tuition was a good idea but required a progressive approach.

As first steps, she suggests that government teachers receive a reasonable income and meet their teaching responsibilities during school hours to ensure that all students have equal access to learning.

“Otherwise it creates inequality from a young age,” said Iwasaki, adding that the government education system must be designed to eliminate the need for extra-curricular tuition.

“This means having achievable learning goals for all students and providing them with the same learning opportunities,” she said.

Soe Win Oo said there was no doubt that tuition could be beneficial.

However, he said he is depressed by the emphasis that parents and teachers place on repetition rather than critical thinking.

“When we reach the day that tuition is no longer needed, we’ll know that Myanmar’s education system has recovered,” he said. “If we can’t get rid of it, it will keep on harming future generations of children.”