The teaching of ethnic languages in schools and development of local curricula could deliver both educational and political benefits, and represent critical steps towards decentralisation.

By NICOLAS SALEM-GERVAIS and MAEL RAYNAUD | FRONTIER

IN MYANMAR, as in other countries, education has been central to nation-building projects. In parallel with civil conflict, the central government and those opposed to it have used education for the transmission of various identities that are to some extent pitted against each other. Education has thus become a battlefield of its own.

Schools run by the Ministry of Education, especially under previous military regimes, have transmitted a largely Bamar-centric identity, a process often perceived as an attempt to “Burmanise” the Union.

Mirroring this approach, ethnic-based education providers, particularly those linked to ethnic armed groups, have strived to transmit their own ethno-nationalist perspectives in the education systems they have established. The most striking differences between state and non-state education concern two critical markers of identity: language, principally in terms of the medium of instruction, and history.

This creates two tightly linked but distinct challenges to using formal education as a means for promoting peace and national reconciliation and both are, essentially, challenges of decentralisation.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The first is to build bridges and strengthen cooperation between the non-state education systems – which have an estimated 300,000 students – and the MoE’s system within a national education framework. The second challenge, and the main topic of this article, concerns introducing the teaching of ethnic languages and cultures in the government education system, which provides schooling for more than nine million students.

Apart from the critical goal of promoting national reconciliation, teaching ethnic languages and cultures in government schools would be likely to produce at least two other major benefits. Most obvious is the preservation of the country’s rich linguistic and cultural diversity, but no less important is the improved performance of ethnic minority children in the national education system, because of reduced language barriers.

In this context, it is tempting to consider mother tongue based multi-lingual education, or MTB-MLE, as a solution. Under this system, all children would begin their education by being taught all subjects in their mother tongue, with a gradual transition of the medium of instruction to the national language throughout primary and middle school.

Some non-state education systems are, de facto, mother-tongue based. However, as we have argued elsewhere, this type of system would be extremely challenging to establish throughout Myanmar in the short to medium term.

Using ethnic languages in education – especially under an MTB-MLE system – requires the existence of standard languages. However, beside groups like the Mon, whose language and identity is relatively standardised, the majority of ethnic nationalities constitute highly complex socio-linguistic groups. It is not unusual for multiple dialects and scripts to co-exist within each of the more than 110 languages classified in Myanmar. These variations correspond to specific identities, whose adherents often resist projects to build common languages through standardisation.

In addition, many languages are mainly used in informal everyday or religious contexts and have not been developed for use as a medium of instruction. To do so would require a great deal of time, enthusiasm, commitment and compromise, and would have to contend with competition from more widely spoken national or regional languages that are associated with economic and social advancement.

Shan language being taught at a government school in eastern Shan State. (Nicolas Salem-Gervais | Frontier)

Another challenge is that in many schools, especially in urban areas, children of different ethnicities tend to be mixed throughout the student population. This would make the logistics of providing an MTB-MLE system extremely complicated and very expensive. It would also result in de facto segregation based on ethnicity, among children who are currently educated together.

Ethnicity is extremely politicised in Myanmar and the issues described are particularly sensitive. Any problems that arise in introducing such a system could be exploited for political purposes and used to create controversy within what are usually regarded as discrete ethnic groups, as well as between different groups.

Given these multiple challenges to MTB-MLE in Myanmar, how could a language-in-education policy move forward?

For the time being, the current shift in MoE policy, which began in 2013 and accelerated recently, appears to be a well-calibrated compromise. Though the reforms begun so far are too new to be evaluated, they potentially pave the way for a significant change in the national education system that is likely to bring both political and educational benefits.

The shift is reflected in the 2014 National Education Law, which makes important points regarding the decentralisation of the education system and language-in-education policy. Article 44 of the law states that regional and state governments can introduce the teaching of ethnic languages and literature “starting at the primary level and gradually expanding [to higher grades]”. Article 43 states that ethnic languages can be used alongside Burmese as a “classroom language”.

The term “classroom language”, which was introduced in a 2015 amendment to the 2014 law, should not be confused with “language of instruction”. Although changing the language of instruction is inherent in the MTB-MLE system, “classroom language” refers to using local languages to explain the curriculum, which would remain in the national language. Although such an approach may not bring all the benefits of proper mother tongue based education, it offers much more flexibility and is a realistic and pragmatic solution in the near term.

Instituting ethnic languages as “classroom languages” will require teachers local to the area in primary schools throughout the country; recruiting them would be challenging in areas where most teachers are currently sent in from regions where Burmese is mainly spoken. However, important changes are being made to teacher training and appointment processes that are aimed at supporting the “classroom language” policy.

In addition, ethnic languages have been taught as extra subjects in government schools since 2013. Officially, fifty-four languages are being taught by about 28,500 ethnic language teachers at schools throughout the country.

However, a number of challenges have hampered the further development of ethnic language teaching. One is the low salary, of K30,000 a month, paid to the teachers, who often teach only one class each school day. Another is the varying level of interest among different communities in learning ethnic languages, though it is generally higher in rural areas. Many communities are also unready, in terms of standardising their languages, developing a curriculum and training teachers.

Finally, because the teaching of ethnic languages has so far taken place mostly outside school hours, and has therefore competed with other activities, children and their parents often perceive the classes as being low priority.

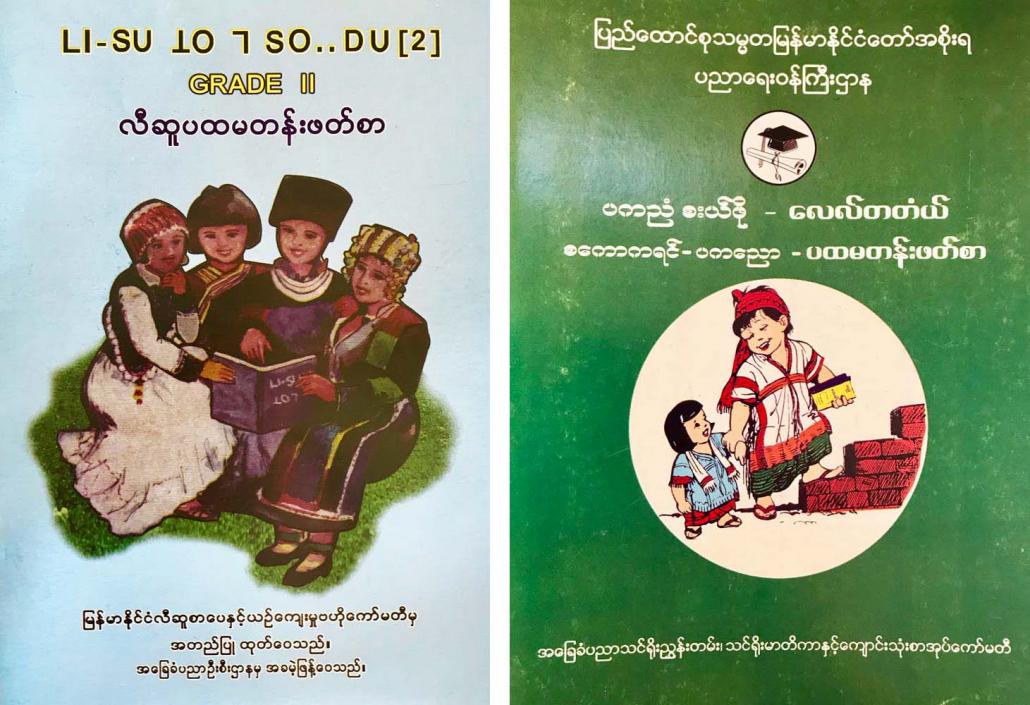

Textbooks for teaching the Lisu (left) and S’gaw Karen languages. (Supplied)

In this regard, the National Education Law contains another important section regarding the partial decentralisation of the curriculum and the teaching of ethnic languages and cultures within normal school hours. Article 39(g) says, “there shall be freedom to develop the curriculum in each region”, working from the national curriculum but attuning part of it to the local context.

Since last year, the MoE and five of the seven state governments, with technical and funding support from the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, have been working to develop local curricula in preparation for the 2019-2020 school year. The exceptions are Shan and Rakhine states, where the process is expected to begin later. Some of the Bamar-majority regions may follow.

Each of these “local” curricula should be taught for five out of the 35 periods in a school week at primary level, Three of these periods should be dedicated to the teaching of ethnic languages. The teaching content would vary from one school to another depending on the ethnic groups different students belong to.

Textbooks for the teaching of ethnic languages are being developed by the numerous literature and culture committees that correspond to different ethnic groups, often with financial and technical assistance from the MoE, UNICEF and sometimes regional governments.

The challenges here are similar in nature to those that would face an MTB-MLE system and include the question of which language, or languages, should be offered at which school, but their magnitude is sharply reduced by the limited scale of the project.

The remaining two periods of the local curriculum should revolve around general knowledge textbooks regarding each state or region. In the five states now participating in the project, a broad range of stakeholders, from regional ministers to representatives of the MoE to literature and culture committees, are holding regular meetings to draft the textbooks, which will describe a given state’s geography and history, as well as the customs, costumes, dances and cuisine of the ethnic groups within the state.

Unsurprisingly, the most challenging aspect of drafting these textbooks concerns history, with each state facing a different set of issues. In a nation marred by civil conflict since independence in 1948, different ethnic groups, even within the same state, often have different perspectives on history. One group’s hero can be another group’s villain.

While the staunch nationalism of some parts of the existing history (and civics) content in the national curriculum is being discussed, and amid deep controversies surrounding the appropriate use of General Aung San as a national symbol across Myanmar, those drafting the new textbooks are currently working towards state-level compromises.

The road to developing the local curricula, which should eventually extend to high school level, is thus paved with challenges and uncertainties. However, in conjunction with the shift towards having ethnic languages as “classroom languages”, the project seems to be a genuine and decisive step towards including ethnic languages and cultures in state education.

In addition to the probable longer-term benefits regarding cultural preservation, national reconciliation and ethnic minority performance in education, these shifts in policy are already bringing together a multitude of actors. Members of literature and culture committees, regional ministers, officials from the ministries of education and of ethnic affairs, and, in some cases, educators close to ethnic armed groups, are meeting regularly to debate and seek consensus on complex and sensitive issues.

Processes such as this, which are creating new political ecosystems, constitute a critical step towards decentralising the Union and building capacity at sub-national levels.