A highly centralised regime for governing “wasteland” is being expanded, with devastating effects on communities trying to reclaim their land after decades of war.

By BEN DUNANT and KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

WE TURNED off the Myeik-Kawthaung highway and a 20-minute car ride down a bumpy track took us to a yard with empty wooden huts and three Komatsu excavators parked side-by side in the midday heat. Further down the track was a row of wooden workers’ houses, where laundry hanging from a window frame was the only sign of life.

We were in one of Myanmar’s largest agribusiness concessions, and all around us a wasted landscape was returning to jungle.

In 2011, the improbably named Myanmar Auto Corporation, a joint venture between South Korean and Singapore companies, received approval from the Myanmar Investment Commission to establish an oil palm plantation over 133,600 acres (54,066 hectares) in Bokpyin Township of Tanintharyi Region in the country’s far south.

However, after clearing more than 13,000 acres of forest in the years that followed, the company was less enthusiastic about planting oil palms. The palm trees cover only 3,351 acres, or about 3 percent of the concession area in the Ma Noe Yone village tract of Bokpyin, according to an analysis of satellite imagery cited in Behind the Oil Palm, a report authored by a coalition of Tanintharyi-based civil society organisations and released last year.

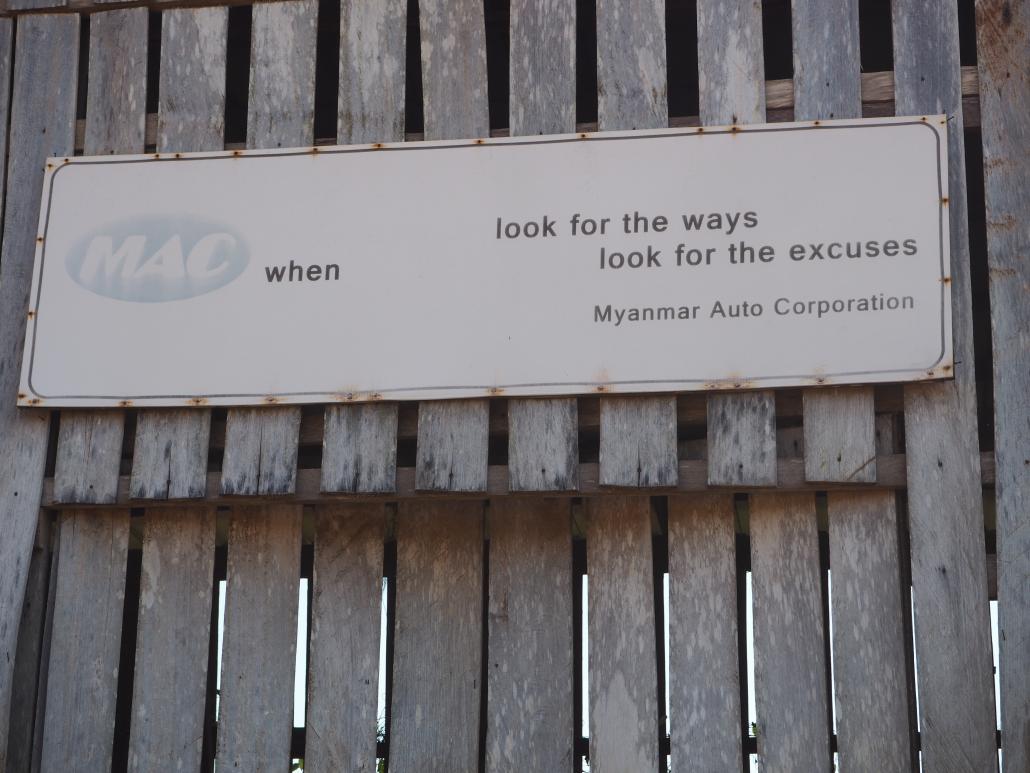

Where palms had been planted, Frontier saw that they were not in the neat rows usually associated with plantations. Instead, the palms had been planted haphazardly over the rolling hills, with clumps of bamboo and grass slowly filling up the wide spaces between them. On one of the empty sheds in the yard, which purportedly formed the administrative hub of the plantation, was a small sign that bore the company logo and some strangely apt words in English: “Look for the ways, look for the excuses”.

The scene in February was not what the former military junta had envisaged for the palm oil sector, which was a core pillar of a 30-year national self-sufficiency plan launched in 1999. Tanintharyi, the only region in Myanmar suitable for oil palm plantations, was to become the “oil pot” of Myanmar. Junta chief Senior General Than Shwe saw large-scale agribusiness expansion as a means of capitalising on Myanmar’s great asset: an abundance of “wasteland” ripe for exploitation.

Yet, the Karen residents of Ma Noe Yone told Frontier that the land reserved for oil palm had not been empty wilderness. Though they now live in settlements along the highway, their original villages lay within the concession area. They had to flee these villages in the late 1990s because of fighting between the Tatmadaw and the Karen National Union and demands for forced labour. The Tatmadaw’s Four Cuts strategy turned their villages, orchards and forestland into a “black zone” where residents were liable to be shot on sight as suspected rebels.

Saw Htun Naing, 25, recalled that as a small boy he had spent two years sheltering on a riverine island and another two years living in the forest because his family “needed to run away most of the time”. In 2001, when the family wanted to return to their village they were warned off by soldiers and settled beside the highway, under close Tatmadaw watch.

Several villagers said Myanmar Auto Corporation had not put the “wasteland” to productive use, but had rather created a wasteland where previously there had been productive forest land used by Karen communities. “They say that they plant palms for oil, but they don’t plant palms; they just want to cut down the trees,” said Saw Win Kyaw, 54, who was employed by MAC as a guide after it began logging the forest in 2013. Win Kyaw believes the logs were intended for export.

Frontier could not reach MAC for comment, but an entry on Chinese e-commerce website Alibaba, under the name of a Mr Harry Han who claims to be an MAC director, seeks “a good business partner in China, India who wants to import large diameter of Keruing and other timber from Myanmar” from June 2013. The post, which is undated, says the timber is coming from “a big logging project of 54,666 hectares” – the same size as the MAC oil palm concession in Tanintharyi Region.

Among those dispossessed of their land is Saw Mahn Eh Bar, 56, who once tended 60 acres of areca nut groves and fruit orchards in the concession area. Compensation was never offered, he said, and even if it were he was not interested.

“I don’t want money; I just want my land back,” he told Frontier.

Villagers said they had appealed to the township Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics for the return of land not being used by the company but providing the necessary documents was a problem.

Mahn Eh Bar quoted the department as saying that they were welcome to apply for permits to use it under the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law, but would need to supply detailed information to support their claims. He said that as the claims were mainly historic and concerned land used before they were displaced by conflict, they were unable to supply the required information and no one had so far applied for permits.

It was unclear how the law could help the villagers with their claims when, under its provisions, the company should have already forfeited the concession. Section 4(b) of the law says a permit holder for vacant, fallow or virgin land is required to start using land designated for palm oil production within four years or it reverts to the state. By-laws go further and stipulate that 15 percent of the land must be put to use in the first year, which far exceeds what MAC has planted over eight years.

Residents of Ma Noe Yone whose ancestral lands are lost to an oil palm concession. (Ben Dunant | Frontier)

Automatic trespassers

Although seemingly a minor element in the struggle of Ma Noe Yone villagers to reclaim ancestral land, the law that now governs this land has attracted outrage in recent months. Amendments to the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Management Law enacted on September 11 included a six-month deadline to apply for a permit to continue using land covered by the legislation.

Land users, whether companies or smallholder farmers, who failed to apply for a permit by March 11 or had their application rejected, face eviction and prosecution for trespassing. The maximum penalty is two years’ imprisonment and a fine of K500,000.

The amendments could enable the government to act against companies that are abusing concessions and reclaim land not being used productively. However, there has been concern that weak government capacity, widespread corruption and a lack of knowledge in rural communities about the law and the registration procedures would mean few could meet the deadline and millions of smallholders would become criminal trespassers.

The registration requirement also asks smallholders to exchange what they might consider an ancestral right to a plot of land for a commercial-style permit that is typically valid for 30 years and cannot be legally sold or transferred, even among family members. Although the amended law formally exempts ethnic customary land from its provisions, customary land is not defined in this or in any other law, and is not considered by the Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics when it maps land use, so this exemption can only be arbitrarily applied.

About a third of Myanmar’s land mass is deemed vacant, fallow or virgin and it is overwhelmingly concentrated in the borderlands. Although enacted in 2012, the law was the latest of a series of regulations governing “wasteland” that date to the British colonial era, all of which have been animated by the same impulse to centralise government control of land, to the detriment of ethnic communities’ autonomy and land tenure security.

As the example of Ma Noe Yone shows, the category is often an inaccurate reflection of how land is either used or claimed. Worse, it enables large areas of land belonging to communities displaced by conflict to be made available for commercial development.

On March 8, three days before the registration deadline, Myanmar and international humanitarian groups supporting communities displaced by conflict in the north of the country issued a statement calling for a halt in implementing the law.

“The combination of the current security context and the implementation of the VFV Land Law amendment potentially renders tens of thousands of displaced persons in Kachin and Northern Shan States landless as of 11 March 2019,” the statement said. It raised concern that displaced communities returning to their villages could discover that their land has been transferred to commercial interests or that they would face prosecution for trespassing.

The experience of Karen communities in Tanintharyi, thousands of whom have returned to former conflict areas since the Tatmadaw and the KNU signed a ceasefire in 2012, suggests these fears are well founded. There is no distinct right to land or property restitution in Myanmar law, and attempts by Karen to reclaim land, such as at Ma Noe Yone, are complicated by the allocation of agribusiness concessions in areas previously “cleared” by conflict.

Imposing a registration deadline and introducing a new trespassing offence merely compounds the existing vulnerability of communities in conflict-affected areas, where few hold title deeds and the burden of proving land claims rests with the smallholder.

Children in Ma Noe Yone village tract, Bokpyin Township. (Ben Dunant | Frontier)

Reclaiming ancestral land

In February, Frontier visited Kye Zu Daw, a Karen village on the banks of the Heinze River in Tanintharyi’s Yebyu Township about 400 kilometres north of the MAC plantation in Ma Noe Yone. Conflict forced most residents of the village, which now numbers about 50 households, to flee the area in 1992; they returned after the 2012 ceasefire to land that had been designated as vacant, fallow or virgin.

Ready to rebuild their lives after two decades of displacement, they found that their original village was within the Tanintharyi Nature Reserve, a 420,000-acre protected area established in 2005 with funding provided by energy giants Total and Chevron as part of a corporate social responsibility programme for the Yadana gas pipeline. As well, 661 acres that the villagers had previously used for orchards was granted in 1999 as an oil palm concession to a businessperson, Daw Yi Yi Win. Villagers do not know where she lives and Frontier was unable to contact her for comment.

The community now lives along a rutted dirt road that runs between the oil palm plantation and the hills of the nature reserve. Data cited by Dawei-based civil society group Tanintharyi Friends in a 2019 report, Between a Rock and a Hard Place, shows that only 250 acres, or 41 percent, of Yi Yi Win’s concession has been planted with oil palms since 1999.

Village leader Saw Chit Win Htoo told Frontier that villagers had been sued three times for criminal trespass since 2016 for trying to re-establish areca and cashew nut groves in undeveloped areas of the oil palm concession, though only small fines were imposed in the first two cases and the third case was dropped. The villagers say that in 2015, Yi Yi Win applied for another 1,200-acre concession under her company’s name, Shwe Padoma. Part of the concession adjoins the village and Frontier saw that trees had been cleared and oil palm planted on a few acres.

Chit Win Htoo said that since August 2016, 33 villagers had applied for permits under the VFV Land Law to reclaim what they say is ancestral land, a process that has so far involved more than two-dozen visits to various township and district level government offices. He said the villagers had received hostile treatment at the offices, including verbal abuse, which had made them suspect that Yi Yi Win and her company were receiving favoured treatment in the competition for the land.

Chit Win Htoo said it would be futile for the villagers to support their applications by paying officials “tea money”, as petty bribes are called. “If we give tea money, the company will give beer money,” he said.

In January, nine of the villagers received permits under the law for a total of 50 acres, all of which is within the 1,200-acre concession granted to Yi Yi Win in 2015, said Chit Win Htoo and other villagers. Claims by another 24 applicants had not been resolved at the time of Frontier’s visit, but villagers said they were determined to reclaim all of the 1,200-acre concession and a sizeable area of the earlier 661-acre concession on which oil palms are yet to be planted.

Frontier telephoned to ask the Tanintharyi Region Minister for Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, U Myint San, about the villagers’ applications and their allegations of abusive conduct by officials but he declined to be interviewed.

Rusting trucks lie dormant among sparsely planted oil palms in the 133,600-acre concession held by Myanmar Auto Corporation in Bokpyin Township of Tanintharyi Region. (Ben Dunant | Frontier)

‘Longstanding confusion’

During a visit to Nay Pyi Taw on March 21, Frontier found that the deep concerns expressed by a broad coalition of civil society and farmers’ groups over the VFV Land Law, and the registration deadline in particular, had failed to resonate in the corridors of power. The situation reinforced perceptions of a breakdown in communication between the government and civil society since the National League for Democracy took office in 2016.

However, when Frontier arrived at the office of U Hlwan Moe, deputy director-general of the Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics, he immediately cut short a meeting with other departmental officials and offered a friendly welcome.

“Thank you for giving us a chance to reply to the criticisms and concerns of community groups,” he said.

Hlwan Moe, who has authored several books on land management in Myanmar, said the purpose of the law was to clarify which lands were available to be used and allocated to various enterprises by the state, in a context of “longstanding confusion”, and that “this is part of the government’s effort to draw more investment”. Since many farmers had “failed to register their land”, he said, “the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Law was amended to push farmers and small-scale land owners to register their lands.” Without the impetus of a deadline, he suggested, land claims would never be clarified.

However, he insisted that the law also presented an opportunity for smallholders to acquire “legal protection” for their land, as long as they conform to the requirements. “If all parties or individuals cooperated with us, then there will be clarity about the land that can be disposed of [by the government].”

Hlwan Moe was eager to assuage fears over possible mass evictions and prosecutions of smallholders after the expiry of the March 11 registration deadline. “I want to make clear that no one will be sued for failing to apply for registration, though the deadline has passed,” he said, adding that the application procedure was simple.

“He or she must come to the township’s Agricultural Land Management and Statistics office, take the application form and fill it out; that’s all he or she has to do. The rest would be our work.” Hlwan Moe said nearly 350,000 applications forms had so far been distributed to farmers at the village level.

Asked how the land rights of internally displaced people would be protected, he cited section 5(b) of the law, which states that “government departments, government organisations and non-government organisations” may apply for land use permits.

This section would allow departments or organisations focused on humanitarian work to secure land for the return or resettlement of people displaced by conflict or natural disasters, but does not establish an explicit right to the restitution of original land and property.

Amyotha Hluttaw MP U Aung Kyi Nyunt (NLD, Magway-4), a member of the ruling party’s central executive committee, said the concerns and suggestions of villagers and NGOs were receiving serious consideration.

He and other lawmakers from the upper house “had recently discussed with the relevant ministries about amending the law again”. However, the work of a joint committee appointed by parliament in February to draft proposed amendments to the 2008 Constitution had delayed consideration of any changes to the VFV Land Law.

He agreed with Hlwan Moe that the fears of millions of farmers being turned into criminal trespassers on land they regarded as they own were unwarranted. The government “would not sue anyone for failing to apply for registration”, because the bylaws to accompany the amendments were still being drafted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. Aung Kyi Nyunt said this meant that the amendments, including the trespassing offence, could not yet be implemented.

Aung Kyi Nyunt attributed confusion over the amendments to the VFV Land Law to a flaw in the language concerning the registration deadline. It stipulated a six-month deadline from the enactment of the amendments and left the government without the required administrative flexibility. He said one of the proposed changes was for a deadline six months after a presidential notification, which would only be issued after the bylaws were completed.

On a shed within the MAC oil palm concession in Bokpyin Township is a sign bearing an apt message. (Ben Dunant | Frontier)

Extending the regime

The journeys to Nay Pyi Taw and Tanintharyi left Frontier puzzled at the sheer level of confusion over how the amended law is being implemented – and even over whether it is being implemented at all. Yet, it appeared that, beyond a readiness to make small changes, the government is committed to a highly centralised regime for governing “wasteland”.

In Tanintharyi and elsewhere in Myanmar, the extension of this regime continues to frustrate the efforts of communities to reclaim their ancestral lands, livelihoods and dignity after decades of conflict and displacement.

Speaking to Frontier in Yangon, Daw Thyn Zar Oo, programme director at the Public Legal Aid Network, which supports smallholder farmers in land disputes, said that successive governments have been motivated by a fundamentally misguided notion of economic development led by large-scale investment.

“Investment and economic development have been poorly defined, strategized and implemented by all regimes that have held office in Myanmar. The result is the constant downturn and the defeat of the whole purpose for almost a century now,” she said. “Without addressing poverty and investing proper effort towards inclusiveness in future development, with all people in Myanmar as stakeholders, no investment of any kind can overcome the difficulties Myanmar is facing.”

Correction: This article has been changed from a previous version that attributed data related to Daw Yi Yi Win’s oil palm concession in Kye Zu Daw village to OneMap, an open-source database for land use in Myanmar that is still being developed. The data was attributed to OneMap in a 2019 report by civil society group Tanintharyi Friends, but OneMap has since told Frontier that it does not match what is on their internal database.